1. Challenges in the Characterization and Categorization of Binding Media in Mummy Portraits

Romano-Egyptian mummy portraits have conventionally been divided into two groups according to , described as (implying an aqueous medium such as glue or egg) or wax (specifically ). Prior to the development of analytical capabilities that allowed for precise characterization, these classifications were assigned largely on the basis of the portraits’ surface appearance and paint handling. More recently, medium descriptions have been informed by scientific data, but even in such cases there remain substantial gaps in the technical knowledge regarding the manner in which the artists made and applied their paint media. Aside from the practical challenges of materials characterization and the limitations of current analytical protocols, an understanding of the painting techniques is hindered by the use of ambiguous terms that have become embedded in the literature and by changes in scholarly opinions and theories about the artists’ methods. This paper examines the technical, historical, and semantic issues that have clouded discussions of the portraits’ binding media, with particular reference to two mummy portraits in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC).

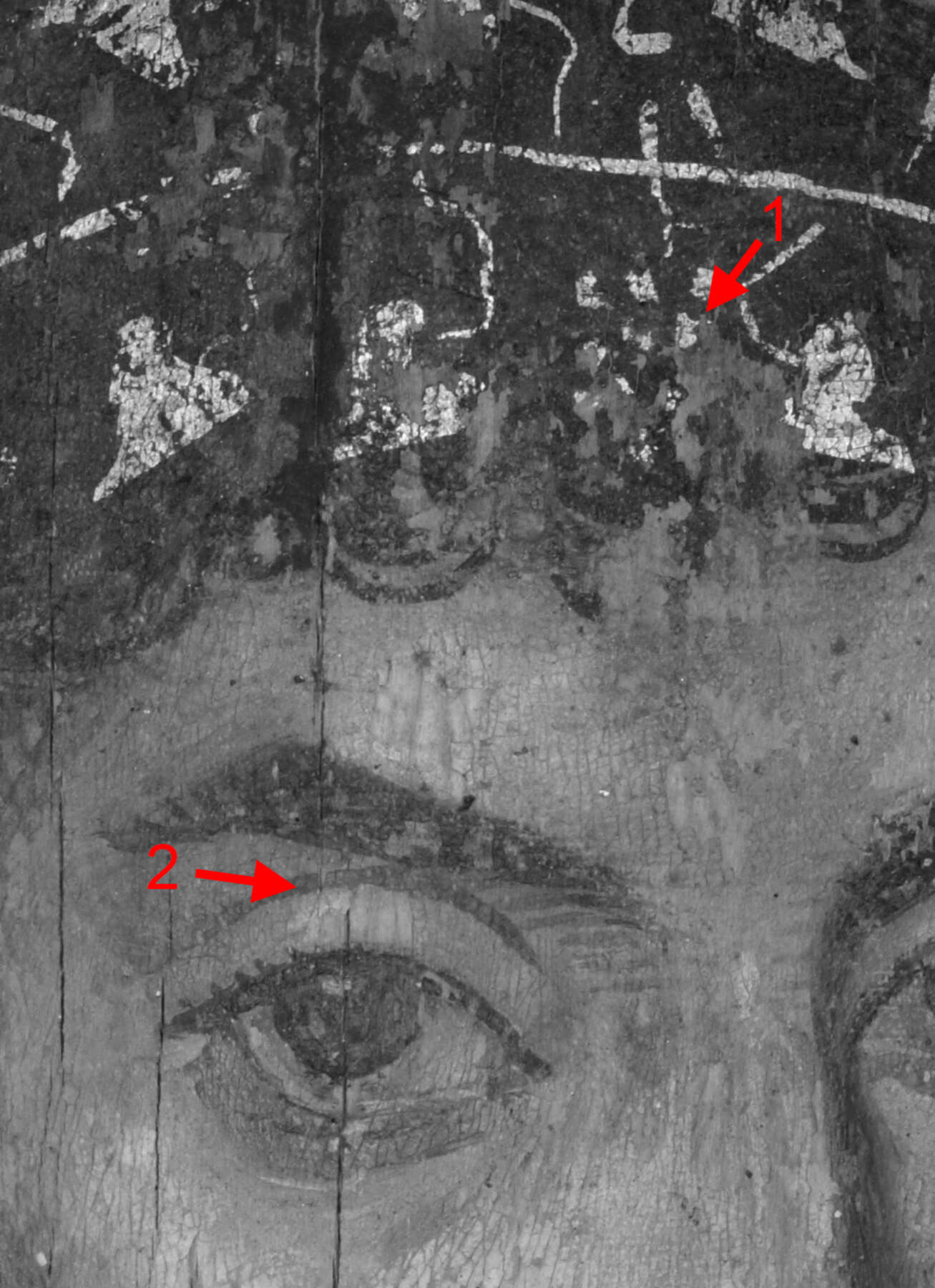

Acquired in 1922, the AIC portraits date from the early to mid-second century AD. Both show vivid likenesses of young men in three-quarter pose wearing formal dress (a white and ; figs. 1.1 and 1.2). The paintings exhibit striking differences in their manner of paint application. One bears the hallmark robust impasto and tool marks indicative of wax applied using the technique (i.e., with the use of heat; fig. 1.3); the other displays a flatter, matte appearance with the distinctive, finely applied lines of tratteggio and crosshatching that are often associated with tempera painting (fig. 1.4). A technical investigation, initiated in preparation for the AIC’s online catalogue Roman Art at the Art Institute of Chicago, was undertaken with the hope of shedding light on this discrepancy as well as other aspects of the portraits’ technique.1 Analysis of the binding medium of the first portrait determined, unsurprisingly, that it was composed of beeswax, supporting a description of the technique as encaustic; however, analysis of the second portrait also revealed the presence of beeswax.2 These findings—along with published studies of several other portraits that lack the visual characteristics of encaustic but that were found, upon analysis, to be wax based3—highlight uncertainties about the precise composition, working methods, and handling properties of the binders. The growing body of scientific data on mummy portraits has been crucial to enhancing our knowledge of ancient painting techniques, but its significance must be carefully and critically evaluated, taking into account the broader problems associated with interpreting and describing these objects. We must also examine our assumptions and preconceptions about the binding media, considering the history and origins of theories about the artists’ methods—as well as the imprecise and shifting meanings of those terms that have been used to describe them.

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.1 Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2 Figure 1.4

Figure 1.4Background: The Origins and Evolution of Ideas about the Binding Media

Speculation about the binding media of the portraits was immediate upon their exposure to the public, following the excavations of Theodor Graf and Flinders Petrie at Arsinoë, , and in the 1880s. It was Petrie himself who proposed that the warm climate of Egypt was sufficient to allow painting with a simple, unmodified beeswax medium4 (and others have made the correlation between the wax medium and the use of very thin wood , suggesting that the panels may have been warmed to further facilitate painting5). But by this time, painting in wax had already been a source of fascination and conjecture for more than a century, prompted in particular by discoveries of ancient wall paintings such as those at Herculaneum and Pompeii, believed by some scholars to have been painted with encaustic. Coupled with the scientific zeitgeist of the Enlightenment, these finds prompted much experimentation to re-create the ancient encaustic technique, described notably in a 1755 treatise by the antiquarian and amateur archaeologist Comte de Caylus6 and in subsequent works by Vincenzo Requeno7 and Paillot de Montabert.8 Many scholars have invoked the writings of Pliny the Elder on this topic and in particular his description of the enigmatic “,”9 the identity of which is still debated today. Pliny’s text is cryptic and open to different readings with respect to the process and product: it has been interpreted as describing the preparation of either a purified/clarified beeswax or one (partially or wholly) saponified by the action of an alkaline salt and thus amenable to application with water in a cold state.10 Despite the sparse evidence, and the challenges of translating archaic texts such as Pliny’s, the theory of the ancient painters’ use of a modified beeswax medium took a strong hold—especially with regard to the mummy portraits. It was promoted in particular by the influential work of Ernst Berger11 and by a general interest around the turn of the twentieth century in water-based and emulsified paint media.12 Some of Berger’s contemporaries challenged his interpretations, however, including A. P. Laurie, who concluded, based on his own experiments, that “we may dismiss [Punic wax] as one of the ingenious fictions that have so long obscured the scientific investigation of the classical methods of painting.”13 To this day, attempts to replicate Pliny’s recipe and to make a workable paint with a saponified “Punic” wax have met with mixed success.14

Aside from the question of saponification, theories have been put forward that the ancient wax medium was modified with additives such as oils and resins to improve its working properties. Such ideas became influential again in the encaustic revivals of the twentieth century, when an assortment of wax painting methods—employing mixed media, solvents, and heating devices—were adopted by artists such as Arthur Dove, Diego Rivera, Jasper Johns, and Brice Marden.15 Several of the painters were inspired by the writings of Max Doerner on this topic,16 and Rivera in particular maintained an aspiration to replicate the “true” ancient encaustic technique.17

This long history of infatuation with encaustic has left us a confused legacy in the literature on mummy portraits. The evolution and persistence of ideas about the media can be illustrated with reference to selected sources: A discussion by Otto Donner von Richter, based on his readings of ancient texts and personal conjecture, and published in Graf’s catalogue of his display of portraits at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, suggests the use (among other recipes) of “Punic wax, balm of Chios, and a very little olive-oil, all melted together over the fire and mixed up with the .”18 Doerner in 1921 describes a “wax paste” made with wax, pigment, and mastic and comments that “it is not impossible that the late Greek mummy portraits from the were made in that way.”19 Similar combinations reappear in the 1990s in the influential work of Euphrosyne Doxiadis, supplemented by the results of her own painting experiments; she proposed that the artists used “hot beeswax … mixed with … Chios mastic, for instance” or “cold Punic wax … mixed with egg … and sometimes a small amount of linseed oil.”20 Although none of these combinations of materials has been indicated to date by scientific analysis of mummy portraits, the recipes are reiterated in authoritative sources such as The Oxford History of Western Art, in which we read that “scientific analysis reveals that several types of encaustic were used … hot beeswax mixed with resin or cold wax with egg and sometimes a little linseed oil.”21 A transmutation from speculation to accepted wisdom to scientifically verified “facts” can be seen in these examples, and once entrenched in the literature such ideas become difficult to challenge or dislodge.

Petrie and Graf’s excavations also brought to light the second category of portrait, often flat and matte in appearance, and sometimes painted in a more naïve style, suggesting that the painters were not working solely in wax. We face similar problems with discussions of this “tempera” group. Like encaustic, tempera was experiencing a revival of interest around the turn of the twentieth century, associated with a renewed scholarly appreciation of early paintings and the translation of historical texts describing their technique.22 The term is chronically ambiguous: in its original and most general sense tempera refers to a paint binder (in the sense of “tempering,” or modifying), and it was only more recently, and largely because of its use in association with medieval and early Italian paintings, that it took on a specific meaning of the “egg tempera” binder typically used in such works. With reference to mummy portraits, however, the descriptor carries the broader implication of a water-based binder, which may include egg, plant , or . While some interpretations of the “tempera” mummy portraits assume an egg medium, likely from conflation with Italian painting methods,23 recent research has revealed that, more often than not, those examples not painted with beeswax are made with animal glue.24

The Impact and Limitations of Scientific Studies

Before the first applications of instrumental analysis to elucidate the portraits’ binding media, many of the widely held theories about their technique inevitably derived from artists’ and scholars’ reconstructions, based on their empirical experience of paint application and informed by interpretations of the fragmentary historical texts. And although replication is a helpful exercise, it can clearly be misleading, as discussed above: the ability to reproduce a painting’s appearance is not in itself compelling evidence that the same method was used in antiquity. Critically, such reproduction doesn’t account for alterations in a painting’s visual and material qualities over time. Similar caution must be exercised when assessing the first scientific studies that appeared in the 1960s and 1970s. These were early days in the development of methods for the organic analysis of painting materials, and while some of the findings have been widely cited as authoritative information, they deserve reconsideration in light of our current, improved understanding of the chemistry and aging of painting materials. In a 1960 paper Hermann Kühn proposed that Punic wax could be discerned from untreated beeswax by the detection of metal carboxylates (soaps) using infrared spectroscopy.25 Raymond White reached a similar conclusion in a 1978 study of two mummy portraits using gas chromatography, suggesting that a reduced proportion of wax esters relative to hydrocarbons observed in a sample from one of the portraits was evidence for hydrolysis resulting from the preparation of Punic wax.26 However, we now know that metal soap formation is a widespread phenomenon in paint films, resulting from the reaction of medium-derived fatty acids with metal ions in pigments such as ,27 and that the discrimination of soaps produced by natural aging from those originally present in the paint—especially in the presence of pigments—is a far from straightforward task.28 And while wax esters seem to be more resistant to hydrolysis than glyceride esters in oil media, some degree of natural degradation of wax esters is likely over thousands of years, depending on the exact burial and aging conditions. Furthermore, the ratio of alkanes to other beeswax components that was the basis of White’s interpretation can be altered substantially by the alkanes’ sublimation over extended periods in a hot and dry climate.29

Even with today’s advanced technology and enhanced knowledge of paint chemistry, we face daunting challenges in characterizing the binding media. A major concern is contamination, which may derive from the original context and treatment of the mummy, its subsequent environment, or later conservation treatments. It’s an unfortunate fact that the most common binding media identified to date in the mummy portraits—beeswax and animal glue—are historically also among the most ubiquitous restoration materials: Petrie himself described the use of both beeswax and paraffin wax to secure loose paint on the excavated portraits,30 and collagen glues have been used for panel repair and consolidation of paint.31 Contamination may also result from the mummification process, such as from residues of adhesive used to incorporate the portrait into the wrappings or excess embalming materials that have migrated through the panel support.32 Considering the portraits’ complex origins and history, and the sensitivity of modern instrumentation, there is clearly a high possibility of encountering a variety of materials unconnected with the original painting technique (wax, glue, oils, resins, starch, etc.) in samples. Knowledge of the conservation history and careful selection of sampling sites are critical to increase the likelihood that information obtained from the analysis is useful; any sampling and further treatments should also be documented thoroughly to benefit future researchers.33 With regard to obtaining credible and representative data, a related problem is the conflict with ethical considerations that may limit the number of samples taken. Additionally, samples must often be taken from existing losses or from the edges of paintings—areas that are more likely to have been subjected to previous restoration or handling.

Another significant challenge in scientific studies is the variety of techniques and protocols that have been used by different research groups, hindering a direct comparison of published results. There is no “universal” method for organic analysis; each provides more or less optimal sensitivity and selectivity for the detection of a given type of material. Furthermore, a method may be selected according to expectations for what is likely to be present,34 potentially creating an unintentional bias in the results. A multianalytical strategy—that is, one that combines complementary information from different techniques—is the most valuable, as exemplified by a recent multi-institutional study comparing the effects of processing and aging on different wax formulations.35 The study provided new insights into the chemical and physical properties of experimentally prepared wax media, but it is humbling to note a concluding statement by the authors that “the scope for differentiating encaustic recipes is limited in ancient samples.” The comment relates that, while we can now readily differentiate the common classes of medium, and in the case of wax, can also see evidence for its age,36 we still have no reliable scientific test to determine how the medium was prepared or manipulated for use in the paintings. In this respect, some of the fundamental debates we have today about the media are not so much different from those that Berger and Laurie were engaged in a hundred years ago.

The Chicago Portraits Reconsidered

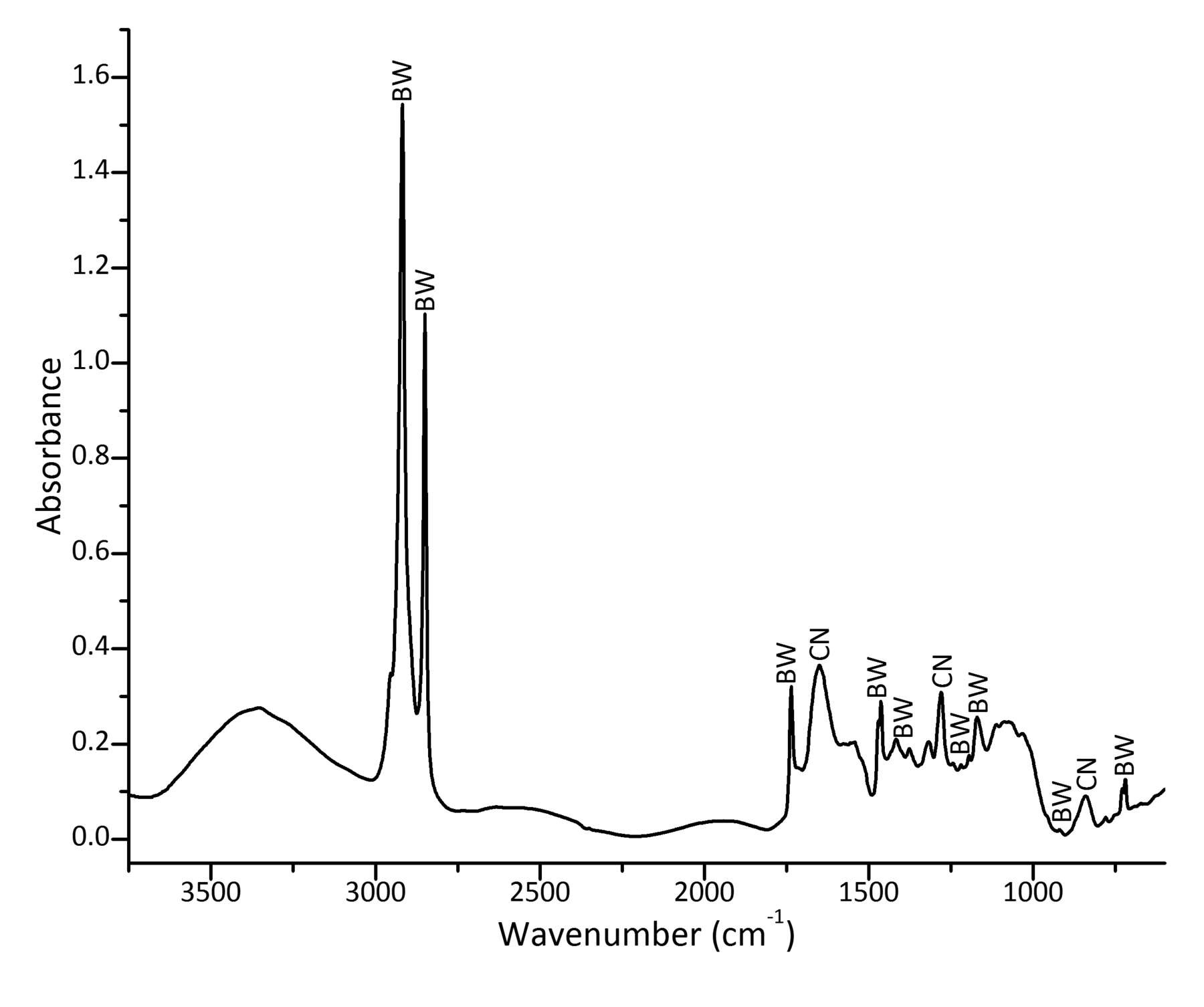

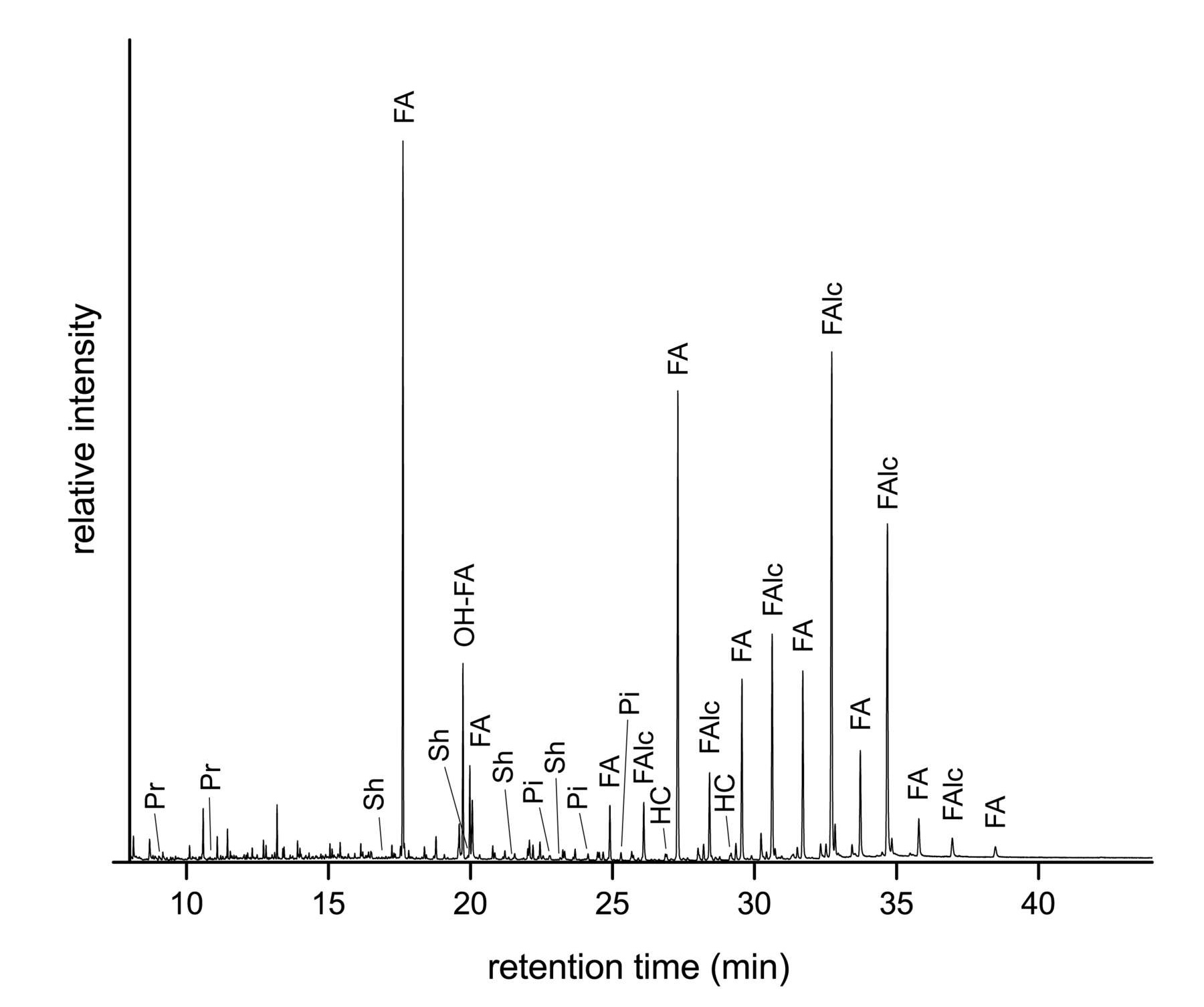

The analytical results from the AIC’s portraits epitomize the issues discussed above (figs. 1.5–1.7). The major component in both paintings is clearly beeswax, with a strong depletion in alkanes characteristic for these ancient objects.37 No general differences were observed in the composition of the wax that might be attributed to some kind of treatment of the medium, such as the degree of esterification or ratios of the various molecular components, to explain the distinct appearance of the two portraits. In addition to beeswax, diterpene (Pinaceae) resin, shellac, a proteinaceous material, and cellulose nitrate were detected in samples from both paintings.38 While some of these materials can certainly be attributed to restoration—the cellulose nitrate, and most likely the shellac—the origin of others is less certain. Is the protein a component of the paint, an accretion from storage or handling, or another contaminant from later treatment? It might be argued that Pinaceae resin was used in the medium, but is this also a residue of some later treatment, or alternatively of an adhesive used to insert the portrait into the wrappings?39 Without the possibility of extensive sampling to determine the distribution of the materials in different parts of the paintings, these ambiguities cannot be resolved with any confidence. While the problem of contamination is frustrating from an analytical perspective, in the bigger picture we can perhaps see a positive aspect, since residues of prior treatments may prove useful indicators of the “biography” of the object, tracking its history and .40

Figure 1.5

Figure 1.5 Figure 1.6

Figure 1.6 Figure 1.7

Figure 1.7The Chicago portraits are not alone in indicating the presence of additional components in wax-based paints. Recent studies of examples in other collections have shown evidence of materials such as oils or fats: portraits from several collections analyzed at the Getty Conservation Institute revealed molecular markers associated with a drying oil and with an oil from a plant of the Brassicaceae family (e.g., mustard oil),41 and one portrait from the Liebieghaus, Frankfurt, was found to contain animal fat in addition to wax.42 Again we are faced with the question of whether these findings provide evidence for an intentional manipulation of the paint. While the addition of some kind of oil to a wax medium to improve paint handling is not implausible, a broader collection of data derived from systematic studies of well-provenanced portraits in different collections is necessary to support the interpretation that such additional materials are deliberate additives and, if this is the case, to clarify whether their use represents a widespread painting technique, a local workshop practice, or isolated anomalies. Ongoing, collaborative research efforts such as those promoted by the APPEAR project will be invaluable in resolving these uncertainties.

Clarifying Nomenclature

Effective scholarship depends on the use of a clear, consistent, and shared vocabulary, something unfortunately lacking in the study of mummy portraits. The unqualified use of the binary encaustic and tempera is unhelpful, as we have seen, implying much while specifying little. Some researchers have proposed terms such as cold wax or wax tempera to account for wax-based paintings that appear flat or brush-applied without the expected textural features of encaustic.43 But the basis for these descriptors lacks a clear consensus, either from scientific analysis or from the interpretation of historical texts, and it denies the more prosaic possibility—as initially argued by Petrie—that certain artists may simply have had a facility for working rapidly with molten wax paint rather than relying on a special modified medium.

Based on current knowledge, our discussions of the media would instead benefit greatly from a more precise and objective use of existing terms. Encaustic should ideally be reserved for portraits displaying visual evidence of application using heat, and preferably supported by analytical confirmation of wax. The more generic term wax (or beeswax) would be appropriate where this medium has been identified but there are no clear visible indicators such as tool marks. This distinction respects the etymology of encaustic, referring to a technique and not only a material, and avoids any unsupported implication of the manner of preparation or application. The problematic tempera could be remedied by simple qualification: glue tempera where there is analytical confirmation of a proteinaceous, animal glue medium, or similar terms such as gum tempera in cases where a more unusual water-based medium is identified. And when describing the medium, one should always make explicit whether the assignment is determined analytically or inferred from similarities in appearance to other known examples.

In a broader sense our problem with terminology stems from the basic human impulse to classify things neatly and simply, which forces reductionism and generalization and stands in direct conflict with the human tendency to be creative and idiosyncratic. Even if we can agree on a descriptive system, we should not be surprised if ongoing research on these enigmatic portraits uncovers further anomalies and exceptions to our categories.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our colleagues who have generously shared their expertise and insights in numerous helpful discussions: Francesca Casadio, Karen Manchester, Katharine Raff, and Cybele Tom at the AIC; Patrick Dietemann at the Doerner Institute; Joy Mazurek at the Getty Conservation Institute and Marie Svoboda at the J. Paul Getty Museum; Richard Newman at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Johanna Salvant at the Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France; and Jevon Thistlewood and Susan Walker at the Ashmolean Museum. We extend our thanks as well to Caroline Cartwright of the British Museum for performing wood analysis on both portraits.

Notes

- See . Specific aspects of the portraits’ technique are discussed in ; a publication describing the analytical results in more detail is planned. ↩

- Criteria for the identification of beeswax have been discussed elsewhere; see, for example, . Analysis was carried out using and pyrolysis with thermally assisted hydrolysis and methylation (THM-Py-GCMS). For FTIR, samples were mounted on a Specac diamond compression cell and analyzed in transmission mode at 4 cm-1 resolution and 128 scans per spectrum using a Bruker Hyperion microscope with MCT D315 detector, interfaced to a Tensor 27 spectrometer bench. For THM-Py-GCMS, samples were placed in Agilent micro vials with tetramethylammonium hydroxide reagent (1.5 μL of a 2.5% solution in methanol) in an Agilent Thermal Separation Probe and inserted into the Multimode Inlet of an Agilent 7890B GC. The GC was equipped with an Agilent HP-5ms Ultra Inert column (30 m, 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film) and interfaced to a 5977B MS. The inlet, operated in splitless mode, was ramped from 50°C to 450°C at a rate of 900°C/min to perform pyrolysis. The final temperature was held constant for 3 minutes and then decreased to 250°C at a rate of 25°C/min. The GC oven was programmed from 40°C to 200°C at 10°C/min, then to 310°C at 6°C/min, and held isothermally for 20 minutes; total run time was 54.33 minutes. The MS was run in scan mode (m/z 35–550 from 5–25 min, and 50–700 from 25 minutes). ↩

- ; . ↩

- : “Wax, coloured so as to absorb the heat, will readily soften and run under the glow of an Egyptian sun; and, with a water bath for the pans of colour, wax would be quite as easy a vehicle to work with as oil.” ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- . For the encaustic revival in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, see also . ↩

- Pliny, Natural History, vol. 6, bk. 21, par. 49. ↩

- ; ; . ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- , 45. ↩

- , 93–102; ; ; . ↩

- , 17–61. ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- . The “balm of Chios” referred to by the author is specifically described as the liquid resin obtained from Pistacia terebinthus (sometimes called “Chios turpentine”), rather than mastic resin obtained from P. lentiscus. ↩

- , 142. This 1934 edition is the first English translation of Doerner’s book; it was initially published in German in 1921. ↩

- . See also . ↩

- , 58. ↩

- . ↩

- , 48; , 9; , 130. ↩

- ; ; . A widely cited description of a mummy portrait with an egg-based binder is reported in ; however, the basis of his interpretation (fatty acid ratios as determined by GC) is dubious in this context without corroborating evidence, and recent reanalysis of paint samples from the same portrait has indicated a glue-based medium: see Mazurek, this volume. have reported a combination of wax and egg in the binding medium of one portrait in the collection of the Liebieghaus, Frankfurt; the significance of this unusual combination of materials is not clear. ↩

- . Similar arguments for the use of saponified wax, or of wax mixed with triglyceride oil–derived soaps, have been made in more recent studies: ; ; . While some authors do not specify the type of soap detected (lead, sodium, etc.), others claim that a specific identification allows a distinction between saponification resulting from deliberate treatment of the wax and saponification resulting from natural aging. This has not yet been demonstrated convincingly in historical samples, however. ↩

- . White’s results are reiterated in , 6; they were later cited by Doxiadis (, 97) as “proving beyond all doubt” the use of Punic wax. ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- , 84: “By putting a coat of fresh beeswax over [the portraits] the old colour was revived and safely fixed…. In later years, paraffin wax was used for this purpose.” ↩

- ; , 135. ↩

- , 8. See also Petrie’s comments on staining of portraits by embalming oil, in , 6; , 117. ↩

- See , 126; , 9. ↩

- This is true especially for GCMS analysis, for which the selected sample preparation and analysis parameters generally provide optimal detection of a limited range of chemical compound classes. ↩

- . ↩

- From depletion of the more volatile alkane components of the wax; see . This phenomenon could have diagnostic value in cases where contamination from a modern application of beeswax is suspected. ↩

- . ↩

- Nine samples were analyzed from variously colored paints in portrait AIC 1922.4798 and six from AIC 1922.4799. Pinaceae resin was identified based on the detection using THM-Py-GCMS of oxidized abietane acids such as dehydroabietic acid (DHA), 7-oxo-DHA, and 15-hydroxy-7-oxo-DHA (see ); shellac from the presence of aliphatic and cyclic hydroxyacids such as butolic, aleuritic, and shellolic acid (see ); and protein from the presence of several pyrolysis products (see ). ↩

- Pinaceae resin, or pitch, was identified in samples of resinous material, presumably adhesive from the wrappings, from the edges of both portraits. The detection by THM-Py-GCMS of retene, along with other oxidized abietanes, suggests the use of heat in the preparation or extraction of the resin. ↩

- See Barr, this volume. ↩

- See . ↩

- . ↩

- , 180–81; , 107; . ↩