10. A Study of the Relative Locations of Facial Features within Mummy Portraits

This paper explores the positioning of facial features depicted in mummy portraits of various different styles and dates, as drawn from the APPEAR database, by bringing together two parallel studies that were undertaken by the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and Cranfield University in Shrivenham, United Kingdom, and Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, United States.

Mummy portraits, also referred to as portraits and often described as Greco-Roman or Romano-Egyptian, date from the first to the third centuries AD. These painted faces were inserted or incorporated into the wrappings of embalmed human remains, although many portraits now exist without their associated mummies. Discussions of their cultural influences often include references to the Greek ancestry of some of the Fayum residents;1 Greek painting styles and techniques;2 the importance of Roman identity, as reflected in the deceased’s appearance; and the traditional Egyptian techniques of preparing and presenting the dead. As such, mummy portraits are often seen to “stand at the meeting point of Egyptian, Greek and Roman worlds.”3 The depicted likenesses are often near life-size and represent a human face. At their most realistic some of these portraits are readily recognizable as the faces of real people who once lived, and yet they still have a group identity that connects them to other, more stylized examples.

The most obvious similarity among the mummy portraits as a group is the general presentation of the face. The deceased almost always assume a similar pose, in which the shoulders and the head are slightly rotated, by different measures, in the same direction. Together with an almost invariably calm reserve reflected in his or her expression, this posture gives the impression of a formal process of image making; however, it could also be an indication that the faces are conforming to a predetermined and generally accepted form. This idea that many different faces can share a group identity under certain conditions of presentation was succinctly described by John Berger as “pictures from a photomat.”4 In the context of photographs for official identification, it is certainly true that rigorous control of particular aspects of presentation can enable individual facial features to be clarified and more easily scrutinized. For an image of identity to be successful there clearly must be a balance between repetition (facilitating comparison yet risking anonymity) and features that convey individual differences; however, in the case of a painted portrait, it is a person—and not a photographic process—who creates the image. According to Prag, in his comments on a male mummy portrait,5 “the artist cannot have painted it without a model somewhere along the line, for one cannot create such a countenance out of thin air…. It lacks the personality that an individual skull with its own individual proportions would have given it.”6

Prior to the period when it is generally believed mummy portraits were painted, several proportional systems were in place and could have been influential. They vary from the Egyptians’ evolving use of proportional grids and measurements7 to the apparently mathematical-based Greek models of ideal beauty, attributed to sculptors such as Polykleitos.8 Arguably the simplest of approaches for the proportions of a human head was noted by Marcus Vitruvius in his Ten Books on Architecture (30–10 BC).9

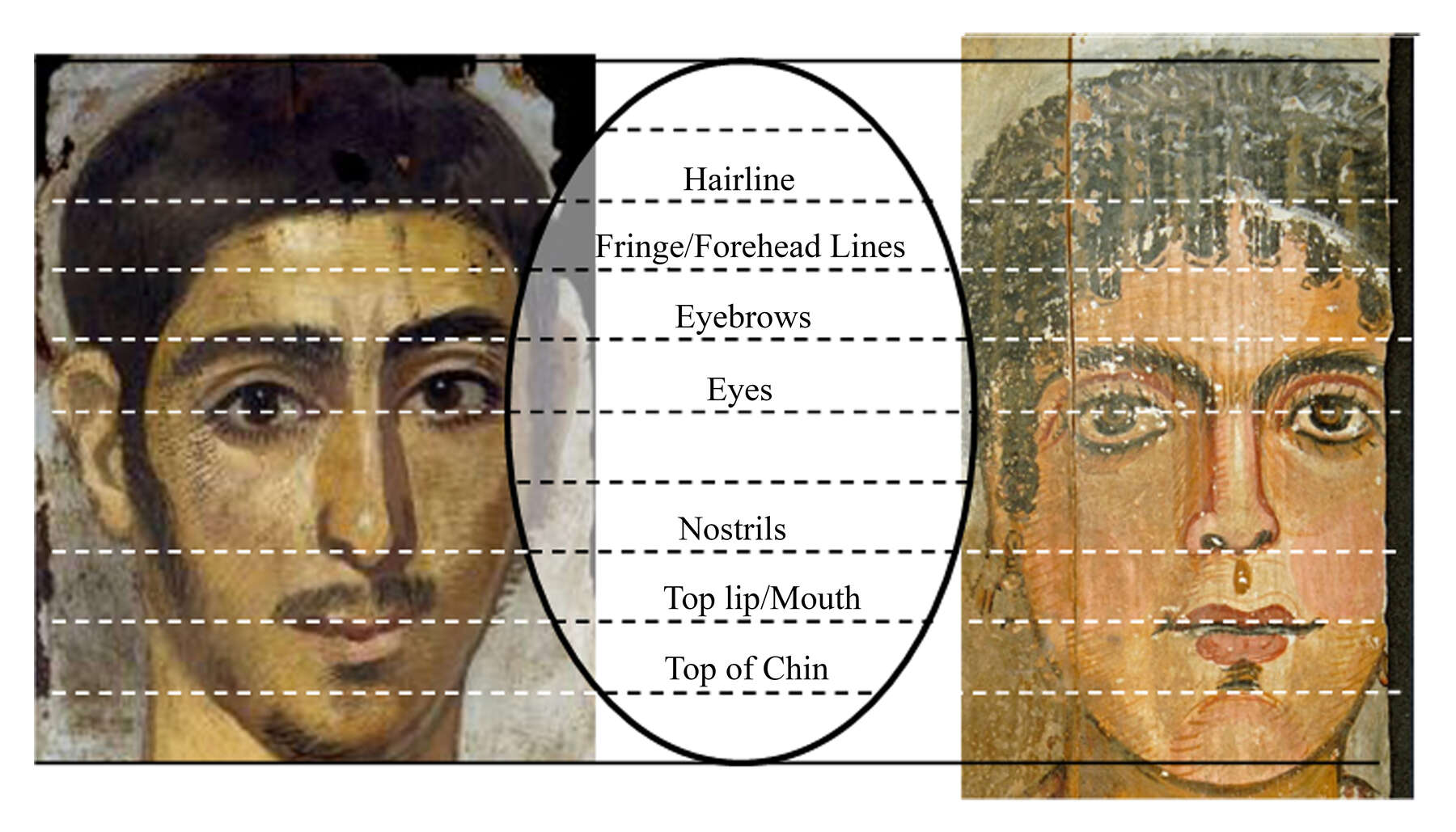

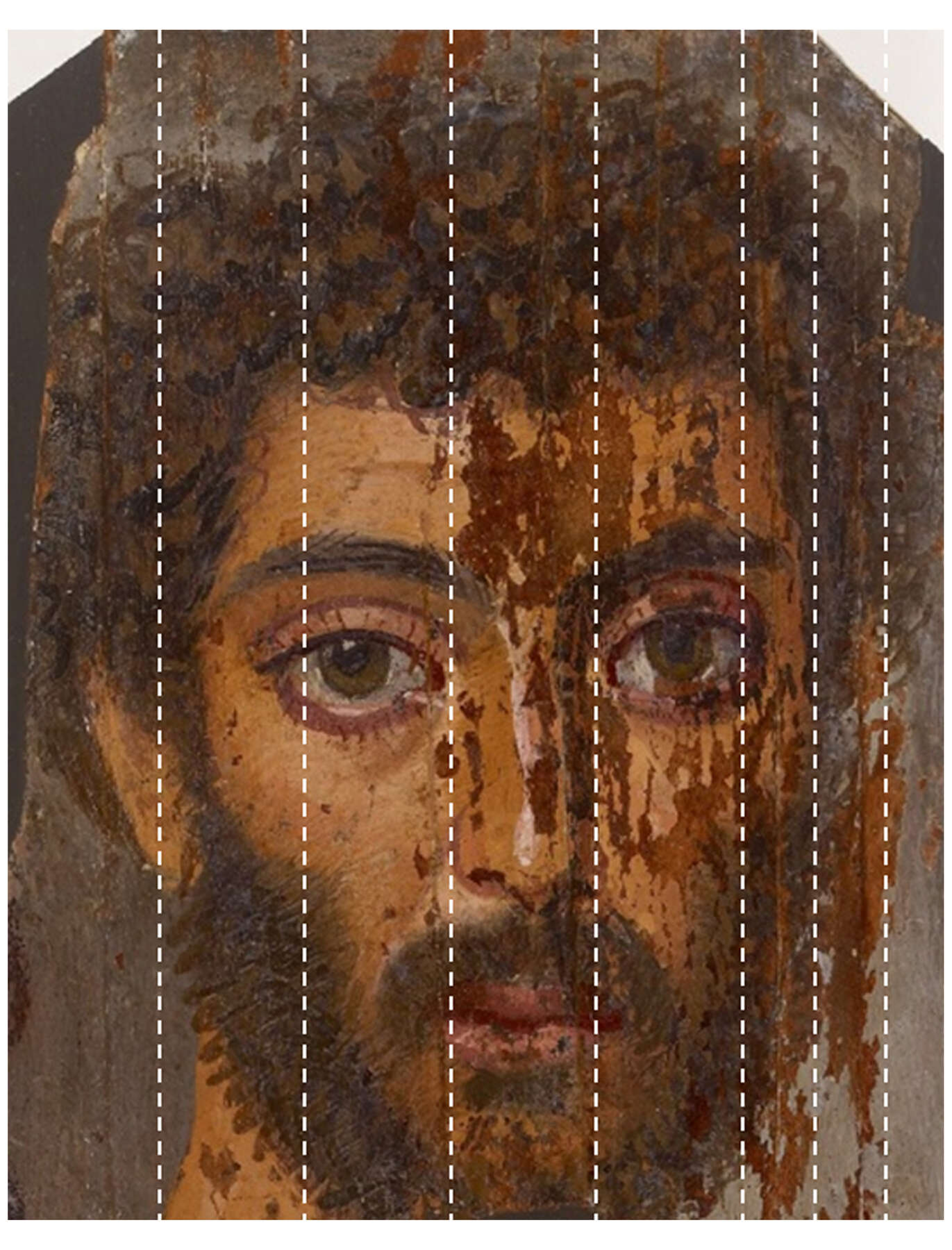

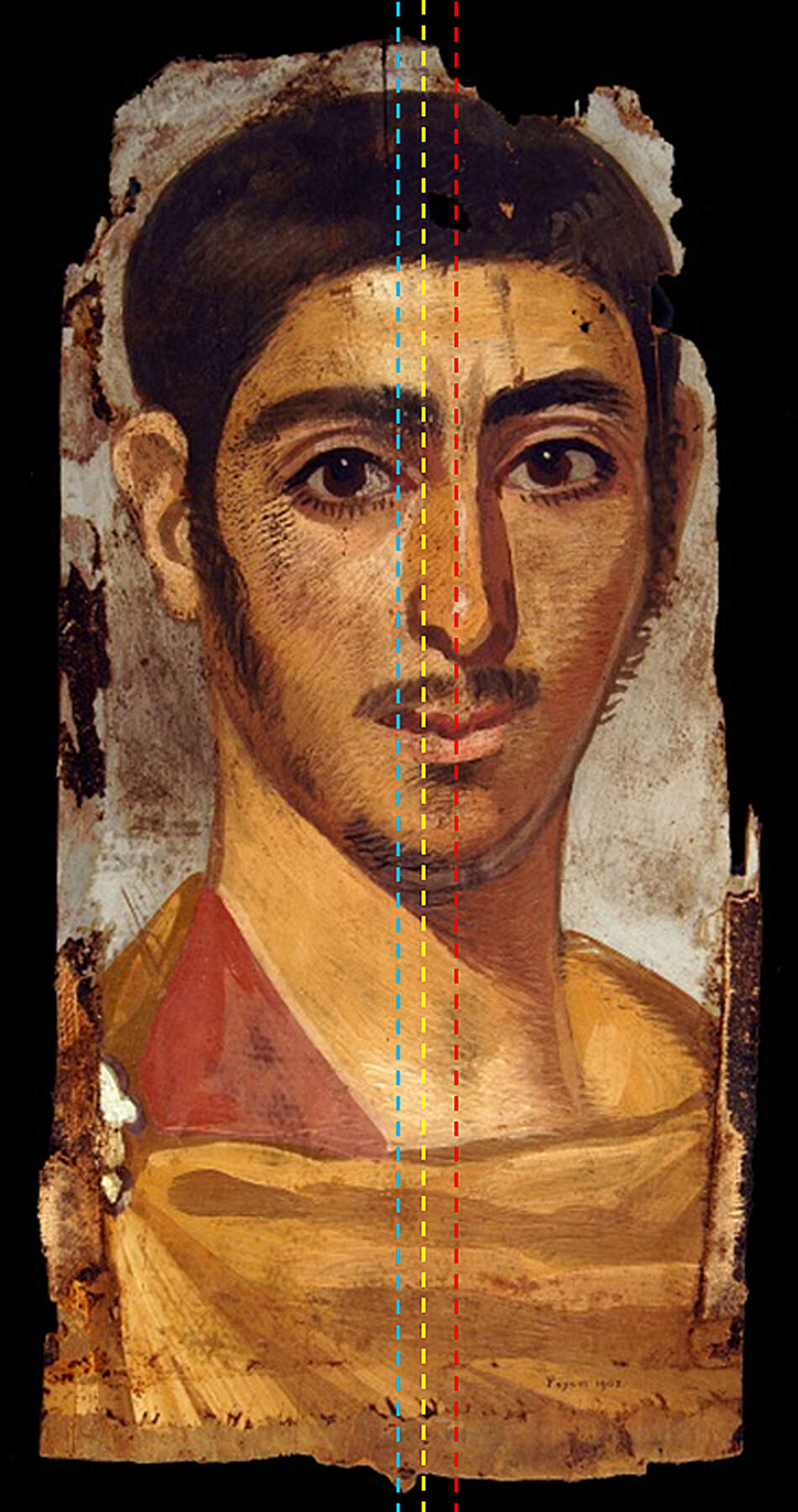

In terms of generally locating horizontal reference lines in the facial features of mummy portraits, a system based on ten equally spaced divisions is readily apparent (fig. 10.1). This spacing seems consistent on all mummy portraits studied to date (with only a few exceptions showing discrepancies in the upper limit of the hair, possibly due to a lack of height with certain hairstyles). At the time of writing, no other painted portraits outside of those characterized as mummy portraits have been found to possess the same regular, horizontal spacing of facial features, suggesting this format could be unique to mummy portraits.10 The uniform, repeating spacing down the face makes it possible to quickly and reliably locate the hairline, the fringe or forehead lines, the eyebrows, the eyes, the nostrils, the top lip/mouth, and the top of the chin. For an artist painting portraits to a consistent standard, a repeating unit of horizontal distance between facial features would be very useful.

Figure 10.1

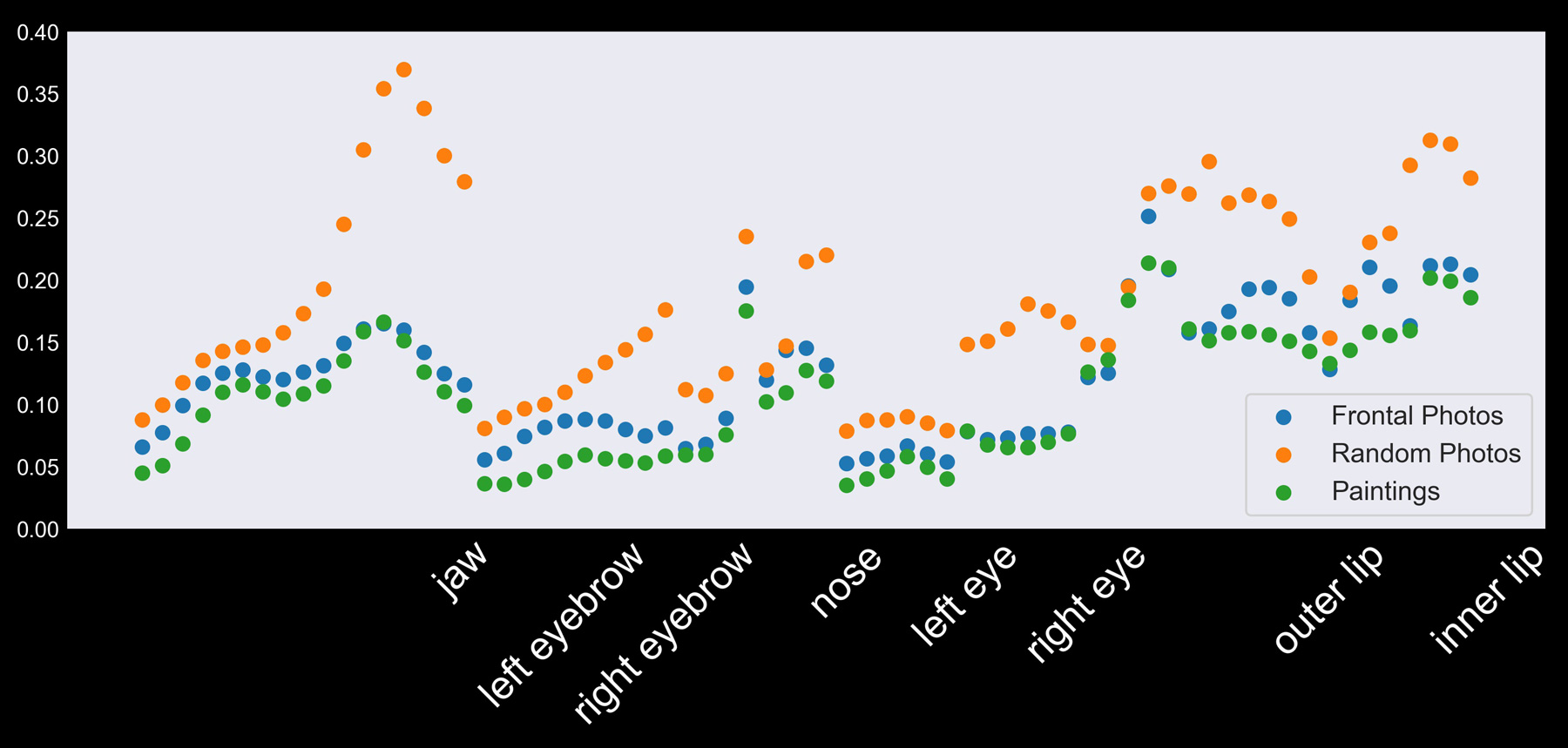

Figure 10.1To explore mummy portrait faces further, an open-source software library module, DLIB,11 was implemented in the programming language Python and used to examine and compare the location of facial features on a set of seventy-two mummy portraits.12 The algorithms underlying DLIB first employ a histogram of oriented gradient (HOG) filter to find the face in a given image and then deep learning to locate sixty-eight reference points for each face. These sixty-eight reference points are a standard set of features that make up the Multi-PIE set13 and are sufficient for many machine-learning tasks, including distinguishing individual human faces in photographs. The exact procedure was applied to the same number of photographs of real faces taken in a variety of positions. The database from which these photos were selected at random includes more than thirteen thousand faces taken from news articles online; the database is appropriate here because the photos it contains were not taken in controlled settings for machine-learning purposes. As such, the faces it contains boast a wide range of poses and expressions.14 A smaller subset was selected randomly for comparison here, by sorting photos alphabetically by the sitter’s last name and selecting the first seventy-two entries, excluding duplicates. Compatibility with DLIB was a constraint that resulted in the exclusion of five images of faces with widely opened mouths, for which facial recognition was unsuccessful. As an indication of uniqueness of pose, the normalized standard deviation in the location of these reference points was calculated for real faces selected randomly as described above; real faces that appeared to have a frontal or slightly rotated pose; and the faces depicted on mummy portraits (fig. 10.2). As expected, different poses present a source of variation; however, on natural faces, this variation decreases when faces adopt a similar orientation. It is thus striking that mummy portraits, as a group, demonstrate even lower variation than do real faces with similar poses. This greater similarity than just having the same pose suggests that when compared with each other purely in terms of locating and scaling facial features, most mummy portraits exhibit a strong underlying format.

Figure 10.2

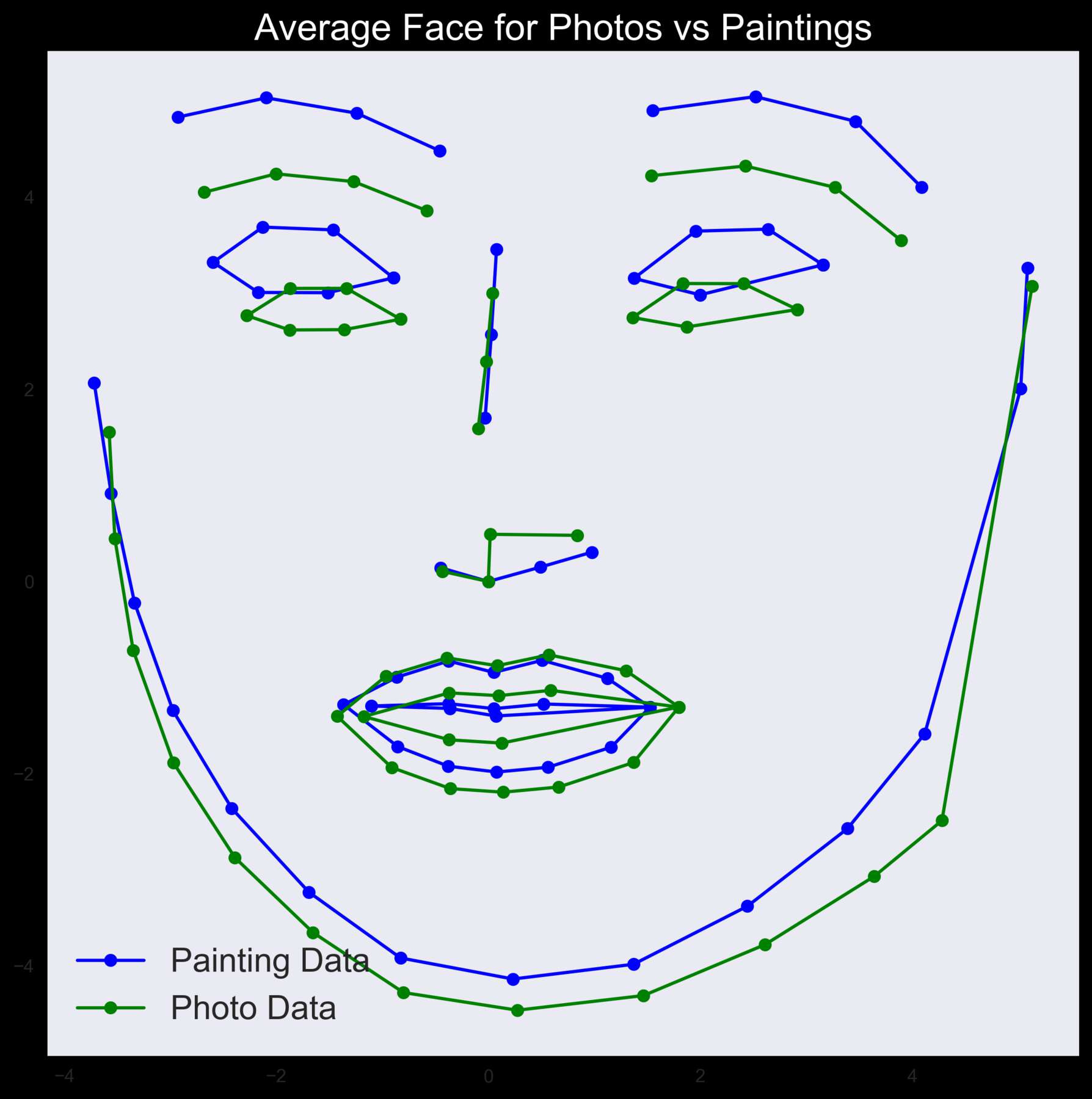

Figure 10.2The average locations of facial features in all mummy portraits taken from the study data set were recorded and plotted, as were the average locations of facial features in the sample set of photographs of real faces (fig. 10.3). Overwhelmingly, in mummy portraits, eyebrows, eyes, lower lips, and chins are consistently positioned higher up on the face than expected when compared with data on images of real faces. Furthermore, those facial features located farther away from the lower edge of a mummy portrait show a greater upward displacement from their expected natural position; however, this shift does not extend to the hairline, which suggests a systematic elongation of the face, extending from the chin to the eyebrows, and a countering compression in the forehead. Figure 10.3

Figure 10.3

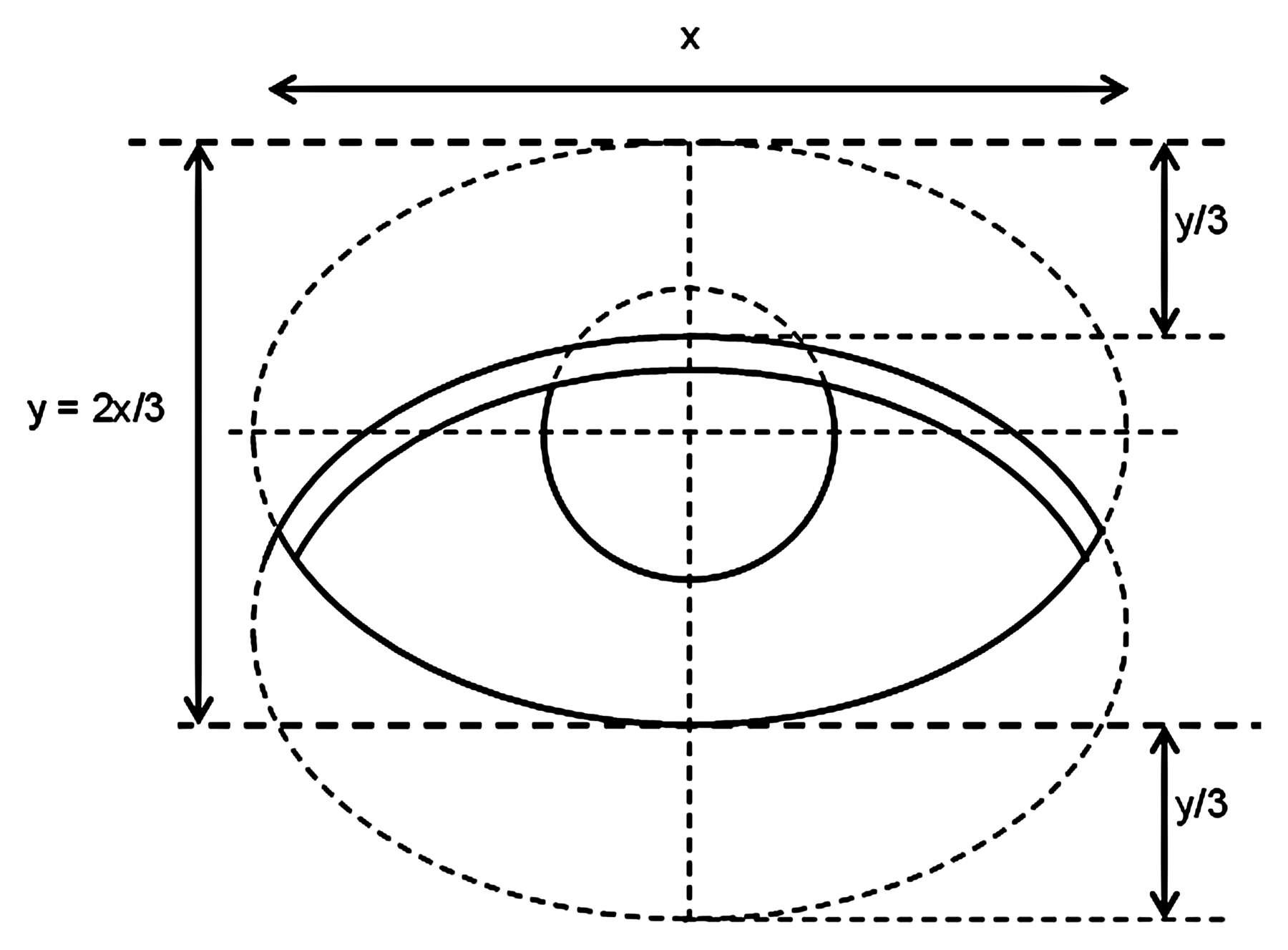

The average facial feature locations on the mummy portraits also draw attention to the large eyes, a striking characteristic.15 In particular, the distance from the top to the bottom of both eyes in all but two of the mummy portraits examined was larger than the average distance found in photographs of real faces.16 Closer comparison of the eyes from mummy portraits of different styles and dates suggests that they also seem to have an underlying correlation in shape and size (fig. 10.4). In contrast, mouths appear slightly smaller than expected—possibly as a counterbalance to the larger eyes. Figure 10.4

Figure 10.4

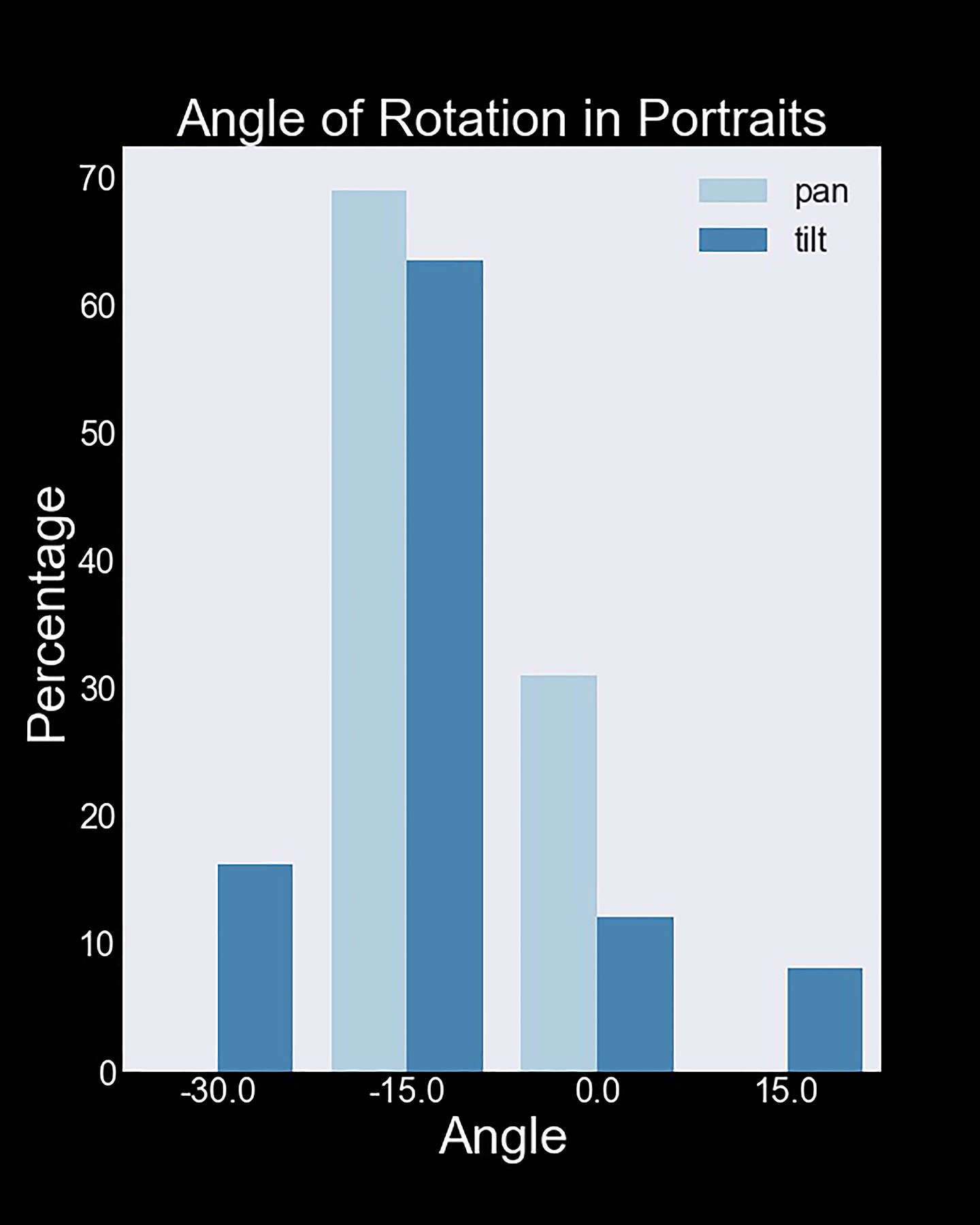

Each mummy portrait was compared with the image of a real face that was angled and rotated in increments of 15 degrees. As a means of measuring similarity between faces at different tilt and rotation angles, each painted portrait was assigned to the photograph of a face for which the sum of differences between corresponding features (the Euclidean distance between vectors containing all coordinates of facial features) was the smallest. This was repeated three times for three different human faces and the results averaged. The majority of mummy portraits compared most favorably with images of human faces that have been tilted both down and to the right or left by 15 degrees (fig. 10.5). However, this effect is, evidently, subtle enough that some other portraits match most closely with faces that are not tilted or rotated. Furthermore, the comparison is relative in that one portrait may be very far or very close on a baseline level from every face with which it is compared, and the comparison still selects only the best fit. This interpretation attempts to understand favorable or less favorable comparisons in terms of tilting of the face. Figure 10.5

Figure 10.5

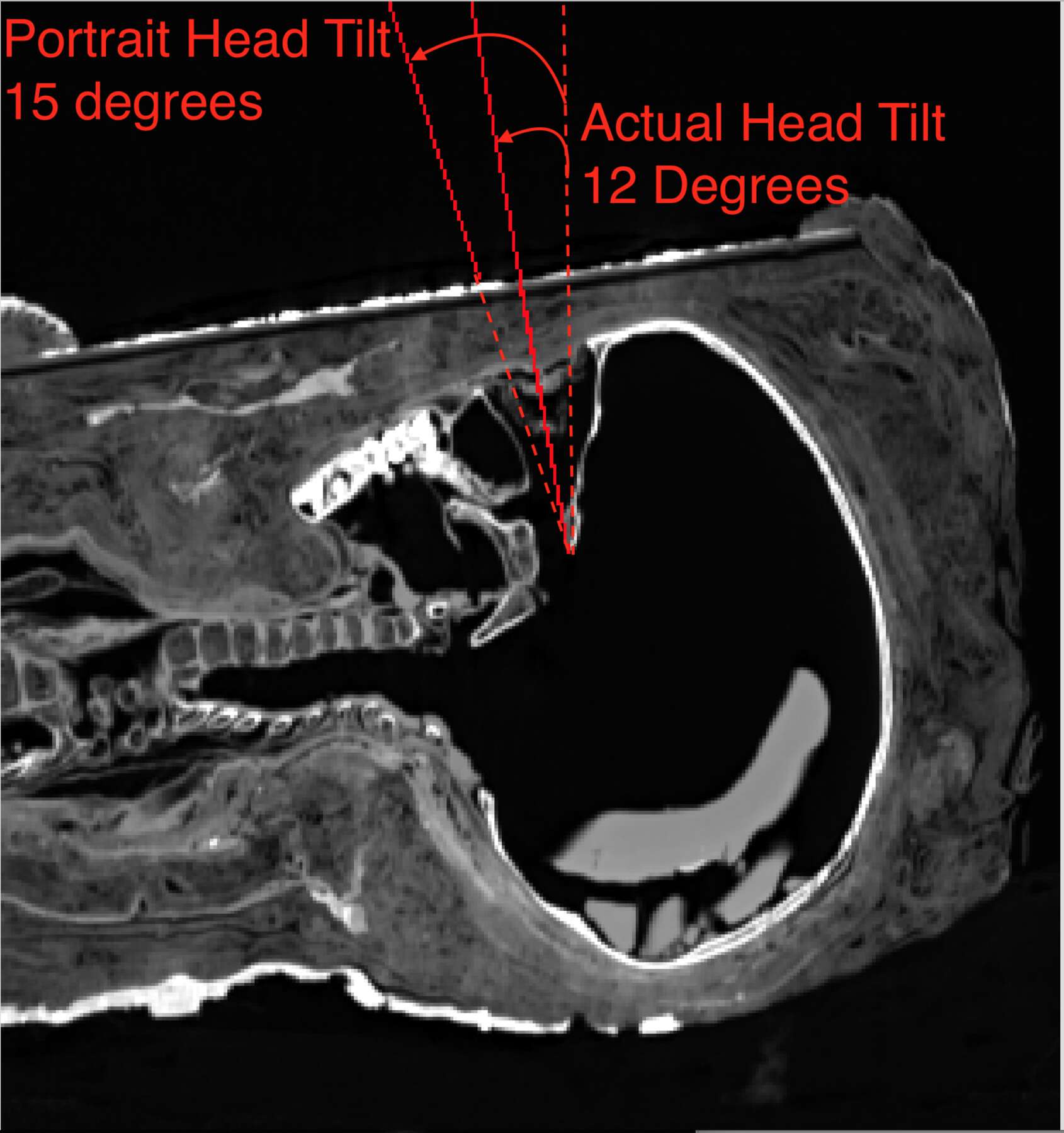

During the embalming process, there are very practical reasons to elevate the head of the deceased at a slight angle by placing it on a headrest. Both the disfiguring effects of blood pooling in the head and an unsightly mouth gaping wide open as the head rolls back at an unnatural angle are best avoided if you respect the dead.17 It is likely that there were also ceremonial reasons for the protection of the neck—and thus the use of a headrest behind it—during the journey to the afterlife. Although little discussed, it is highly likely that most X-ray images or CT scans of related mummified remains will support this notion that heads within mummified remains are often to be found with the skull angled slightly. For example, analysis of a mummy portrait from the Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, Evanston, Illinois, by Northwestern University18 revealed that the head would have been tilted by about 15 degrees during mummification, based on a residue of resin found inside the skull, and that the mummy’s skull as it remains today is still rotated forward (figs. 10.6 and 10.7). Likewise and more relevant perhaps, the mummy portraits themselves, in the context of being attached to a mummified body, should not necessarily be assumed to be lying flat and parallel to the ground; more likely, they too were somewhat tilted forward in line with the positioning of the head and the shape of the mummified body beyond the shoulders.

Figure 10.6

Figure 10.6 Figure 10.7

Figure 10.7The effect of viewing a mummy portrait that is angled forward or backward is an alteration in the perceived proportions of the deceased’s face (fig. 10.8). If the lower edge of the portrait is assumed to be the center of rotation, then tilting forward or backward will cause the relative horizontal positions of facial features to move toward the center in relation to their distance from it. So, features farther away from the lower edge of the portrait will experience greatest displacement toward it. It is therefore apparent that the deviations of a mummy portrait from the expectations of a real face can be temporarily removed by changing the angle of presentation.

Figure 10.8

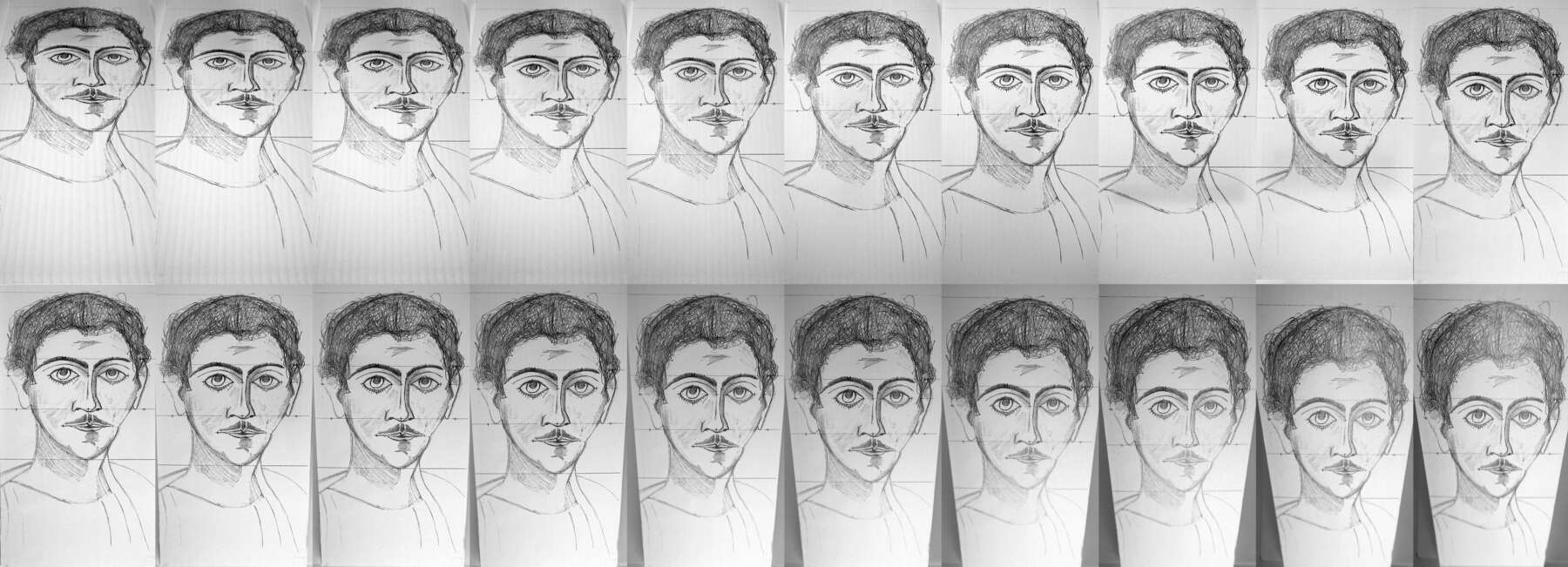

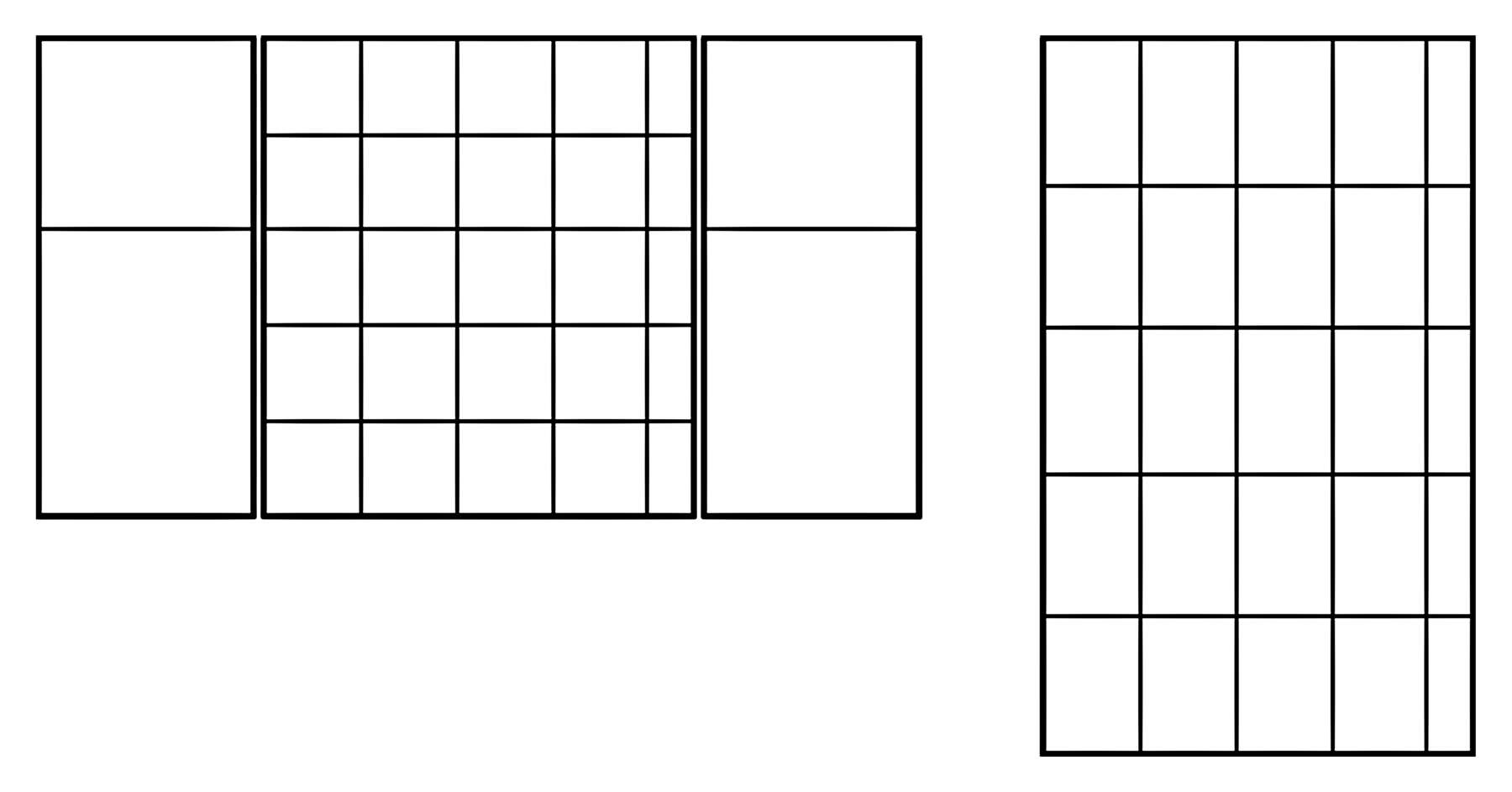

Figure 10.8Citing ancient sources (which are not usually specifically identified),19 authors such as Cennino d’Andrea Cennini (ca. 1360–before 1427),20 Dionysius of Fourna (ca. 1670–after 1744),21 and Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768, citing Anton Raphael Mengs)22 have given guidance on the classical proportions of a human head. With regard to the vertical spacing of facial features, the simplest and most common guide is often based on a division of fifths, with one-fifth equal to the width of an eye. Not only does this help produce a recognizably human face, it also allows an artist to position the eyes and, by extrapolation, the length of the eyebrows and the widths of the nose, mouth, and chin. When heads are turned slightly to one side, the central three-fifths relationship remains true with the nose moved off-center to allow it to be seen in slight profile. To support the illusion of rotation, the outer-fifth spacing on the receding edge of the face is reduced and the cheek and jawline emphasized. This vertical-fifths relationship is likewise evident in the mummy portraits examined (fig. 10.9). There also appears to be a relationship between the relative widths of the ears: the nearest ear generally occupies a whole-fifth division, while the receding ear often accommodates a half-fifth division. In practical terms, the width of the face is effectively four and a half times the width of an eye or the space between the eyes.

Figure 10.9

Figure 10.9When the mummy portraits were compared with images of a real face in rotation, facial recognition software identified the majority of the mummy portraits examined as achieving a 15-degree turn (see fig. 10.5). However, some were identified as looking directly forward despite having the reduction in facial width. This is possibly because in addition to the foreshortening on the receding side of the face, facial features also have to move slightly when the head turns. If we look at the centers of vertical symmetry for features in front of and behind the face, we would expect the nose and lips to move away from the center of the face, toward the receding half. Likewise, the center of the back of the head should move in the opposite direction (fig. 10.10). For most mummy portraits examined, this movement is in small and equal amounts; however, there are some portraits in which this movement is not apparently successful, and these works may register as forward-facing heads. This identification could indicate a mistake in technical understanding, or it is possible that we do not fully understand the intended angle of viewing for some mummy portraits. For example, were there situations in the context of viewing a portrait on mummified remains when viewing directly from the front was not possible or intended?

Figure 10.10

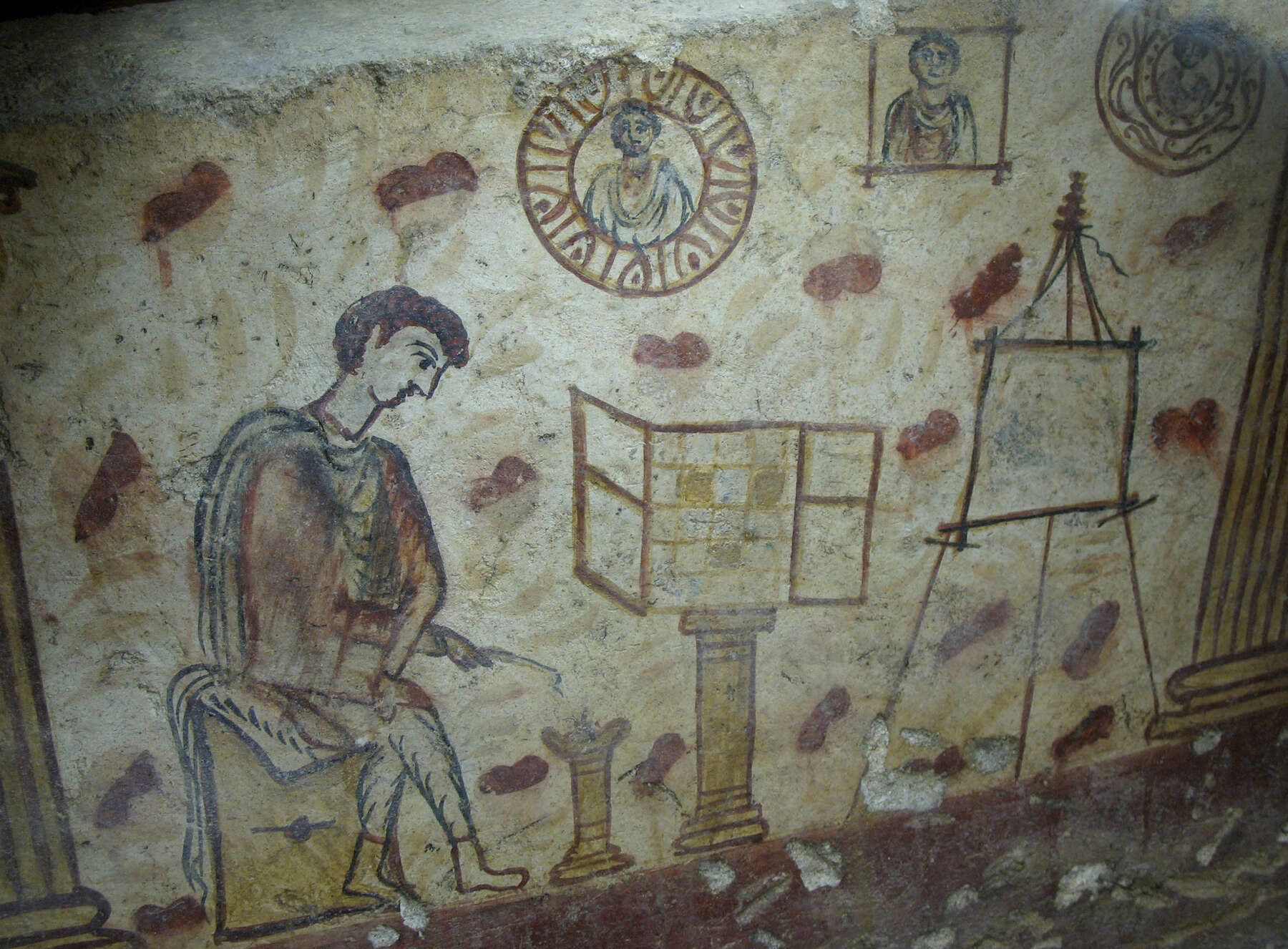

Figure 10.10If we combine the horizontal and vertical reference lines extrapolated so far, we see that mummy portraits can often align neatly to a system of ten horizontal divisions and four and a half vertical divisions. If we simplify the number of horizontals to five, then we are left with a five-by-four-and-a-half grid. This arrangement is similar to a grid depicted in an image of a portrait painter on a sarcophagus dating from the first century BC in the State Hermitage Museum Collection (figs. 10.11 and 10.12).23 Although we do not suggest that an identical grid was used, it is possible that a similar idea could have been initially used to plot the facial features of mummy portraits. It is not inconceivable that, with practice, an artist could master gridlike spacing without an actual grid. The grid on the sarcophagus would suggest equal height and width spacing in the subsequent face depicted; however, the underlying framework of mummy portraits that has been proposed suggests a height-to-width spacing at a ratio of three to two. This discrepancy could be deliberate to allow for subsequent tilting, or it could be a by-product of the angle from which the deceased’s head, or a drawing grid, is viewed.

In conclusion, mummy portraits appear to share a remarkably similar arrangement in terms of the relative size and locations of their facial features. There seems to be a consistent underlying facial format that is unique to these portraits. When the angle at which this format is presented is changed, the facial feature locations and proportions likewise change—and conform more closely to those expected in a real face. Mummy portraits include simple foreshortening and shifting centers of symmetry to achieve the illusion of a turning head. This illusion does not always seem to be successful; however, some of the mummy portraits examined have curved and others are flattened. Without fully understanding the original intent—or not—it is difficult to be certain if curvature is now a missing viewing factor in some of these portraits.

Figure 10.11

Figure 10.11 Figure 10.12

Figure 10.12Notes

- See , 15, 18–19; , 282; , 7; . ↩

- , 84–86; , 144–45. ↩

- , 16–17. ↩

- , 56–57. ↩

- Identified in the article as a portrait of a bearded man, said to be from , ca. AD 150–180 (London, National Gallery 3932). ↩

- , 58. ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- “For the human body is so designed by nature that the face, from the chin to the top of the forehead and the lowest roots of the hair, is a tenth part of the whole height; the open hand from the wrist to the tip of the middle finger is just the same; the head from the chin to the crown is an eighth…. If we take the height of the face itself, the distance from the bottom of the chin to the underside of the nostrils is one third of it; the nose from the underside of the nostrils to a line between the eyebrows is the same; from there to the lowest roots of the hair is also a third, comprising the forehead.” ↩

- Indeed, could this be an additional way to assess those mummy portraits identified as later fakes or forgeries? ↩

- https://github.com/davisking/dlib/blob/master/python_examples/face_landmark_detection.py; . ↩

- This is the number of mummy portraits for which DLIB was successful, and there were many more for which it was unsuccessful. ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- , 93: “When I just now used the word startling, it was with reference not only to the method of painting but also to the apparent disproportionate size of the eyes, which in many even of the male portraits are almost obtrusive.” ↩

- Two mummy portraits with eyes that were not taller are Mummy Portrait of a Bearded Man (32.6) in the Walters Art Museum and Portrait of a Woman (17.060) in the RISD Museum. ↩

- Dr. Richard Lloyd, e-mail message to authors, November 3, 2017. ↩

- . ↩

- See . ↩

- , ch. 70. ↩

- , 12. ↩

- , 209. ↩

- Inventory number П.1899-81, https://www.hermitagemuseum.org/wps/portal/hermitage/digital-collection/25.+archaeological+artifacts/19421. ↩