11. From All Sides: The APPEAR Project and Mummy Portrait Provenance

When the APPEAR (Ancient Panel Paintings: Examination, Analysis, and Research) project was launched in 2013, was not preeminent among its ambitious research aims. But no artwork is absent of history, from the time when it was made until its current circumstance. In this regard, the APPEAR project—which seeks to “increase the understanding of [ancient painting] materials and manufacture”—is perfectly situated to consider the role of provenance when undertaking a comprehensive study of these works of art.1 This paper will focus on select case studies drawn from the corpus of the APPEAR project in order to examine them within the historical context of mummy portrait collections and to explore the role provenance can play in furthering the collaborative objectives of the project itself.

Provenance: A Time Line?

For museums, provenance often signifies a discussion of an artwork’s history of ownership. In this way provenance is a kind of ownership pedigree, and historically, it was a way of championing particular excavators or owners whose inclusion could confer status or authenticity. But the emphasis on these few constituents has often meant the elision of a great deal of history, and for many objects bought on the art market, including mummy portraits, provenances are rarely complete. Traditional object provenances are also often implicit but not explicit—in other words, what is known about an object’s history is emphasized, but not what is absent.2 But provenance has other meanings: instead of ownership history, it can document the place where an artwork was created or the time at which an artwork was first known.

To the scholar Rosemary Joyce, provenance can stretch back to the sources for an artwork’s material components as well as forward through the litany of the artwork’s owners.3 For mummy portraits, perhaps provenance should then be considered not merely in terms of an artwork’s pedigree but in terms of the age of the wood used for its panel, the species of tree from which it was hewn, the traces of prior use, the origin of the , the source for the wax. All of these elements are brought together by the APPEAR project, where provenance and conservation data sets can be considered concomitantly. A mummy portrait’s provenance situated within this broader framework is more like a tree than a straight line, comprising centuries of data points that converge into a single object that then may be transferred, bought, stolen, sold, or even divided into separate fragments.

To many archaeologists, the superseding issue is not an object’s ownership history but an excavation history or at least a secure findspot. This distinction is often delineated by the use of the term to make clear that an object comes from a known, documented context. An unexcavated portrait cannot be fully recontextualized by comparison with excavated material; it must remain, to borrow a concept from the archaeologist Elizabeth Marlowe, on shaky ground.4 But even portraits excavated together may have divergent collecting histories, in which they were displayed, mounted, or sold in different ways, leaving unanswered conservation and provenance questions alike. Mummies bereft of portraits—such as that of a teenager now in the collection at Durham University—are a reminder of the complicated history behind the collection of mummy portraits and of what has been lost.5 Although some portraits undoubtedly were victims of pests, poor burial conditions, or ancient vandalism, other portraits were deliberately extracted from discarded mummies, perceived more salable as artworks without the physical reminder of their origin.6

The distinctions between provenance and provenience are often blurred, and they remain a particular challenge with mummy portrait records, where art-historical attributions to a site based on style or materials have often been conflated with a secure findspot or provenience.7 The APPEAR database allows for the opportunity to reconsider provenance and conservation as essential partners. What provenance alone cannot provide, conservation and material analyses can help reconstruct and retrace. Through interrogating provenance and conservation data together, commonalities in treatment, materials, and composition can be revealed—or old assumptions about a portrait’s history disproven.

Mummy Portrait Collections: A Brief History

The history of mummy portrait and panel painting collections is one rich in both provenances and proveniences, and the rediscovery and later collecting of mummy portraits and panel paintings is well documented in the literature. Egyptian funerary portraits and began gaining a greater prominence within European private collections only in the early nineteenth century, centuries after the arrival of two portrait mummies bought by Pietro della Valle in Saqqara in 1615.8 Two influential figures among the collectors of the early nineteenth century were Henry Salt and Robert Hay, who amassed huge collections of Egyptian material that were largely devoid of provenience. These assemblages were later sold and dispersed to institutions from Europe to North America, informing the development of public collections around the world. Portrait mummies and shrouds from the Salt and Hay collections represent some of the earliest documented examples from the APPEAR corpus.

Perhaps the most formative figure in the collecting of mummy portraits was Theodor Graf, an Austrian carpet dealer with establishments in Alexandria and Cairo. His agents turned toward the fertile burial grounds of the in the 1880s as a source for funereal textiles and ancient papyri.9 Precisely how and from whom Graf acquired all of his portraits remains opaque, although records include names of some local dealers like Ali (Abd el-Haj el-Gabri) and Farag (Ismail).10 In 1887 the discovery of hundreds of mummy portraits, which Graf then exported en masse and promptly exhibited in major cities across Europe and America, ignited both artistic imaginations and art-historical fervor. Despite media attention from displays in venues such as the World’s Columbian Exposition, the commercial market for Graf’s portraits was perhaps less than desired, as hundreds of portraits remained unsold at the time of his death in 1903.11 Graf’s portrait collection, which is relatively well documented through sale catalogues, dealer photographers, and exhibition publications, provides crucial data points for exploring the emergent market for mummy portraits at the turn of the century.

Concurrent with the mummy portrait exhibitions mounted by Graf from 1888 to 1893 were the discovery by the archaeologist William Flinders Petrie of portrait mummies at in 1888 and his own subsequent exhibitions in the Egyptian Hall at Piccadilly in London.12 Graf was not alone as a purveyor of mummy portraits, as the public could view these images through a growing number of collections, like that of Augustus Pitt-Rivers, whose acquisition ledger includes mummy portraits acquired from Petrie in 1888 and from Greville John Chester in 1889.13 This display was notable enough that the Baedeker guide singularly listed “some Greco-Egyptian mummy-portraits from the Fayoum” as among the paintings on view at Rushmore in 1890.14 That Pitt-Rivers’ portraits reached rural England only a short while after the arrival of Graf’s collection in Vienna is again testimony to the rising celebrity of mummy portraits within the art world and to the tightly linked networks of funders, excavators, and diggers between Egypt and Europe.15

By the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, the systematic excavations at Hawara, , Tebtunis, and other sites added hundreds of portraits and their essential documented contexts to the growing corpus of panel paintings.16 As always, Klaus Parlasca’s monumental study of more than a thousand mummy portraits remains a fundamental resource for provenance research.17 This paper would not be possible without Parlasca’s careful cataloging of the movements of these portraits, especially those on the art market, which are otherwise poorly documented. Given this complicated history, it seemed appropriate to consider the composition of the APPEAR project entries in terms of their provenance.

The potential of a partnership between provenance and conservation—by presenting the data of both disciplines together as part of the same database—is what first drew me to the APPEAR project. But in order to start looking for commonalities, I needed to determine what data existed on the provenance of these portraits currently (May 2018) in the APPEAR database. To create this preliminary assessment, I collected data from a wide number of sources: provenances in individual entries, online museum collection pages, publications by Parlasca, exhibition catalogues, dealer advertisements, auction catalogues, dealer archives, and information provided by colleagues both at the Getty and throughout the APPEAR project.18 As a caveat, the provenance information for some portraits remains incomplete, unpublished, or both, and future studies may incorporate new information not available at this time.

Of the 278 individual portraits, paintings, and fragments currently entered into the APPEAR database, just over one hundred come from documented excavations. Two others are likely to have been owned if not excavated by Petrie but cannot be connected to specific records; five portraits had no provenance information available from the APPEAR project or from publications that would confirm their categorization. That leaves 166 portraits, or just under 60 percent of the portraits in the database without a secure documented provenience. Of them, four have been described as forgeries. This set of 166 unprovenienced portraits is split almost evenly between ex-Graf and non-Graf groups.

Although the Graf collection was historically associated with , the burial ground for the ancient city of Philadelphia, more recent scholarship has challenged this assumption; the diversity among ex-Graf portraits preserved within the APPEAR database alone warrants caution.19 The eighty-four Graf portraits currently make up roughly one-third of the APPEAR database, and one-quarter of the suggested total of 330 portraits and fragments once owned by Graf, making the APPEAR database an unparalleled resource for understanding the composition of his collections. These portraits constitute significant portions of both Graf’s initial collection, often referred to as Graf I, and the collection revealed only after his death, Graf II.20 The celebrity nature of Graf as an owner has often overshadowed later collecting histories accrued by ex-Graf portraits, even for portraits still on the art market more than a century later; in this way, the APPEAR project also allows for the dispersal of the Graf collection to be more critically examined. It should be noted that more than thirty additional portraits and mummies are a part of APPEAR institution collections but are not currently a part of the database, so future analyses will lead to different breakdowns across all categories of provenance and provenience data.

To return to the excavated material, the APPEAR database contains portraits from at least eight sites: Hawara, Tebtunis, Kafr Ammar, Fag el-Gamus, Thebes, , Tanis, and Karanis. Excavated material from at least six additional sites—Marina el-Alamein, Saqqara, Abusir el-Melek, Antinoöpolis, Akhmim, and Aswan—is not currently represented, although several portraits within the database have been stylistically attributed or ascribed through market provenances to some of these sites.21 The excavated portraits represent a narrow array of early excavations, from Hawara in 1887 to the Karanis excavations of 1926. Understanding and confirming the overall geographical distribution of the portraits within the APPEAR corpus is critical so that any limitations on the data available can be understood within the appropriate context.

The portraits acquired on the art market are, as expected, a far more heterogeneous group. They represent both the earliest and the latest acquisitions in the APPEAR database: from an intact portrait mummy in the British Museum, acquired from Henry Salt by 1821, to a portrait acquired in 2009 by the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston.22 As referenced above, the unexcavated portraits include stylistic attributions to or market provenances suggesting connections to a wide variety of sites, including Hawara, Antinoöpolis, er-Rubayat, Akhmim, Kerke, Thebes, El-Hibeh, and Saqqara. Unlike the excavated portraits in APPEAR, which overwhelmingly entered into museum collections soon after excavation, the portraits acquired on the art market have histories that are often complex and nonlinear. For example, C. Granville Way donated two shrouds to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1872, but they were documented decades before, in 1836, as part of the Robert Hay Collection in Scotland.23

Given the large percentage of Graf portraits in the database, it follows that the acquisition dates of many APPEAR portraits reflect the dispersal of that collection in the early decades of the twentieth century; however, Graf portraits continued to move into and out of private collections and museums, and the APPEAR corpus includes additional acquisitions by museums throughout the twentieth century of mummy portraits with no known connection to Graf or his agents. As a whole, the APPEAR project represents close to two centuries of mummy portrait collection, excavation, display, and treatment.

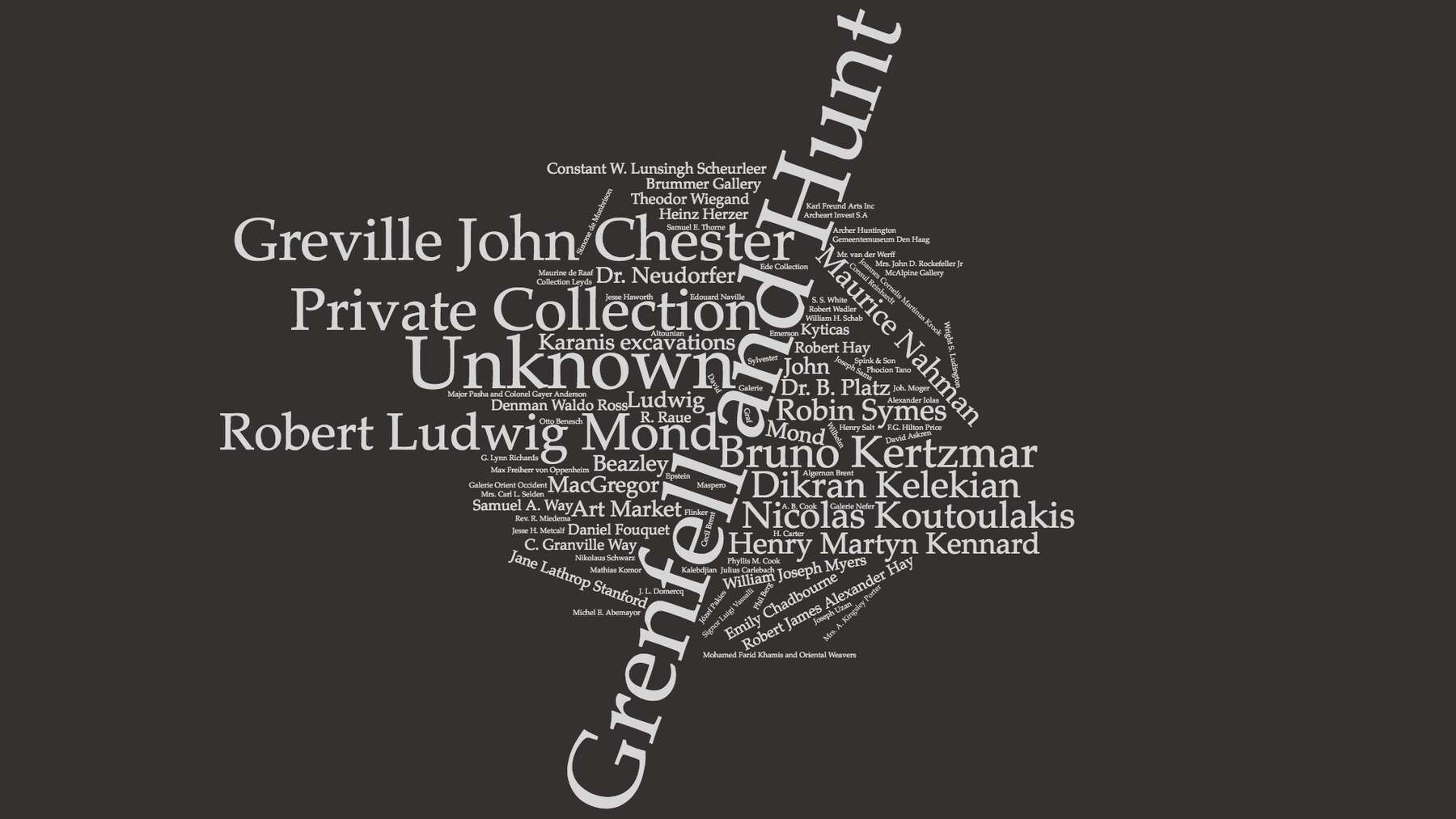

Unsurprisingly, two names dominate the provenances of the APPEAR portraits: William Flinders Petrie and Theodor Graf, the two figures associated with both the largest group of excavated portraits and the largest private collection of portraits, the latter group all unprovenienced. The word cloud in figure 11.1 excludes Petrie and Graf for the purposes of illustrating more clearly the other constituents identified as involved with the APPEAR portraits. To create this image, a tally was included for every figure identified as part of a portrait’s history, including a site’s excavators, patrons, dealers, and donors. Within this framework, some portraits are associated with multiple figures and others with very few. The discrepancy in available information means that this compilation is not intended as a complete plot of every provenance for every portrait, but it serves as a beginning toward mapping emergent patterns. The negative space documents the unknowns: the names of the anonymous people who first found and handled the portraits that formed many early collections; the intermediary agents and dealers whose own preferences for and treatment of the portraits is also undocumented; and the amorphous category of “private collection,” which elides so much of the combined collecting histories of ancient panel paintings. Although Graf’s singular collection is often treated as a metonym for the art market trade in portraits, Graf operated within a far broader constellation of dealers extending into the twentieth and even twenty-first centuries. By acknowledging and considering the wider circulation of portraits on the art market, other connections may be drawn in the future between portraits across the APPEAR project.

Figure 11.1

Figure 11.1Tracing Provenance: A Museum Collection as Case Study

To return to the Getty’s own collection, the APPEAR project arrived at an opportune moment. Over the past five years, a small team of researchers has worked on the provenance of the forty-six thousand objects and fragments in the antiquities collection, so the APPEAR project was a welcome chance to reassess what information was known about the provenances of the Getty’s portraits. The recent reinstallation of the Villa’s collection provided further opportunities to photograph and analyze the mummy portraits traditionally on permanent display. All sixteen of the panels, portraits, shrouds, and portrait mummy were acquired by the museum or donors through the art market between 1971 and 1991; none of the works are known to have been archaeologically excavated.

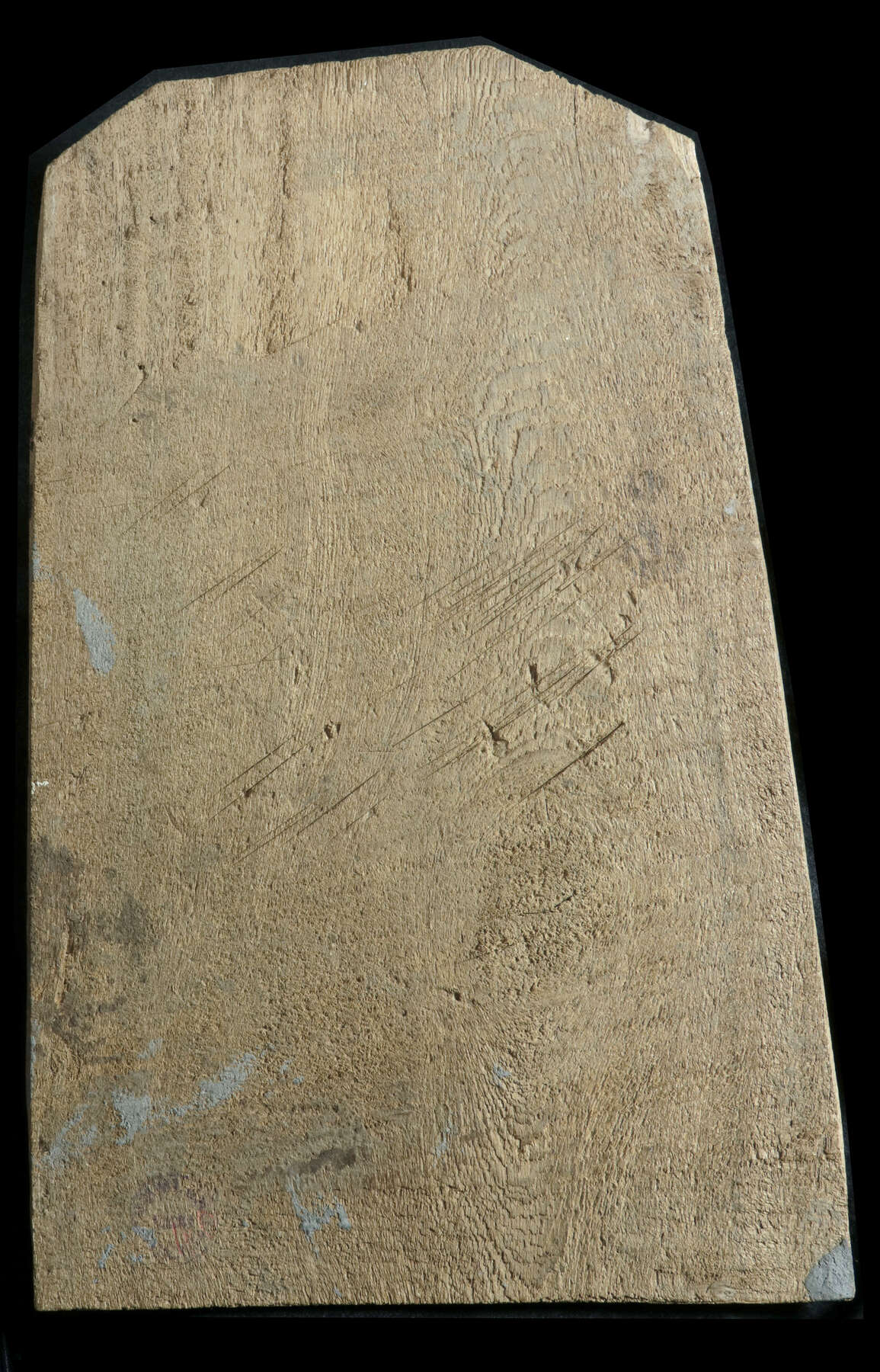

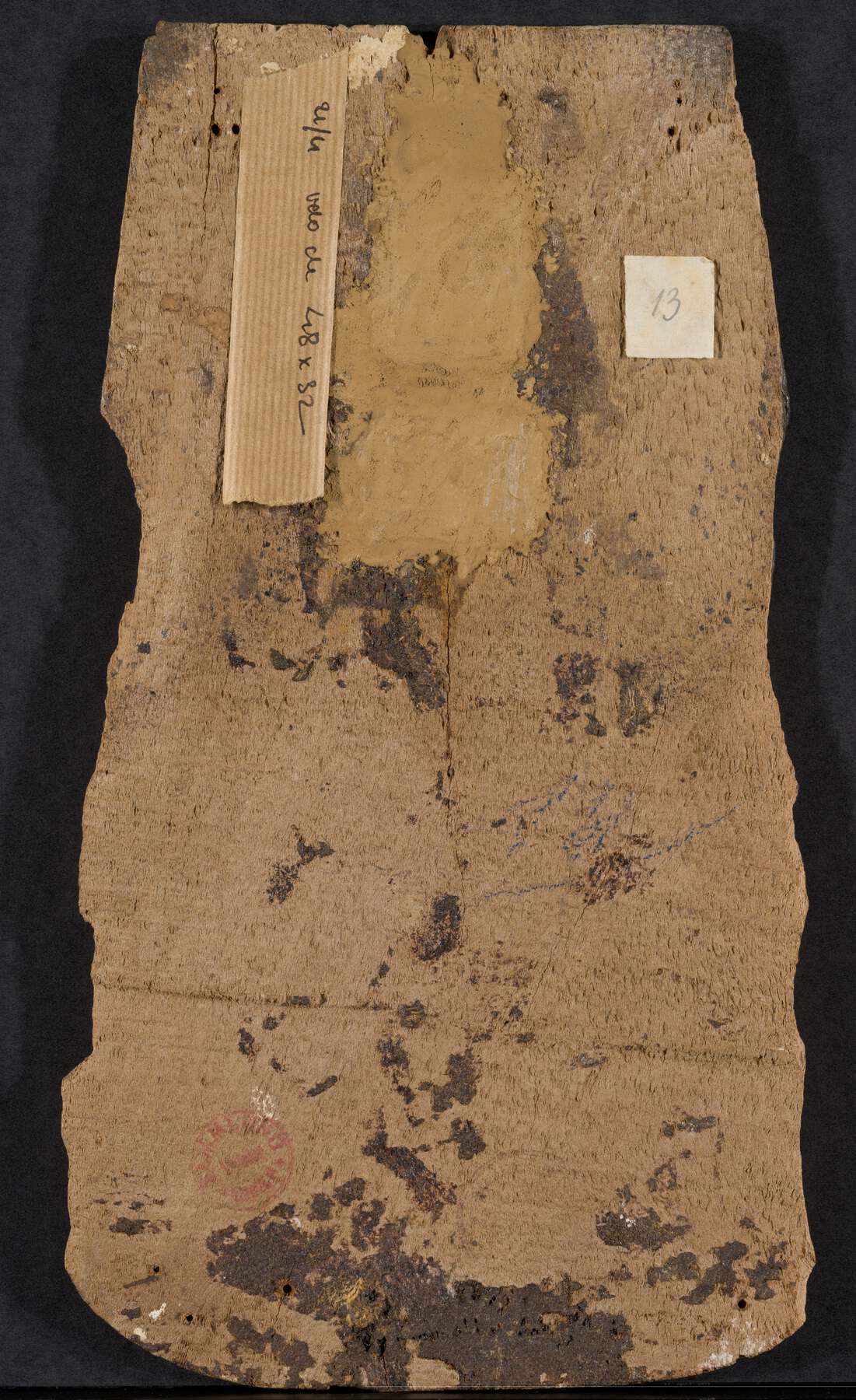

In beginning to assess their histories, one primary tool was the portraits themselves. It is no surprise that the reverses of ancient panel paintings, like those of their modern counterparts, have been infrequently discussed and rarely published. The relative rarity of ancient panel paintings has also meant that post-acquisition, many portraits have been on near-constant display, precluding any comprehensive documentation of marks, stickers, stamps, or labels on their reverses. To date, these markings, often themselves of unknown provenance, are seldom referenced in museum publications or catalogues.24

Because so many portraits in the APPEAR project were part of the Graf collection, the APPEAR database serves in particular as a repository for Graf-related ephemera of all kinds.25 Graf once owned at least two of the Getty’s portraits, Mummy Portrait of a Woman (79.AP.129) and Mummy Portrait of a Young Woman (81.AP.29), although their respective provenance histories include many detours between their departure from Egypt and their final acquisition by the Getty (figs. 11.2 and 11.3).26 Although Mummy Portrait of a Young Woman was never published as part of the Graf collection prior to Graf’s death, the portrait’s provenance is clear from the reverse, where a round purple stamp with the legend “SAMMLUNG THEODOR GRAF” is preserved (fig. 11.4). This stamp indicates that the portrait was part of Graf’s second collection, as it was only applied to those portraits handled by the art dealer Bruno Kertzmar by 1930.27 Even fragmentary portraits were stamped, as seen in a narrow fragment in the Allard Pierson Museum, where the stamp overlies an artificial backing.28 This stamp is often accompanied by paper labels with photo negative numbers, visible on numerous other APPEAR portraits (see fig. 11.6), but no other labels are extant on Mummy Portrait of a Young Woman, indicative of differential preservation. Figure 11.2

Figure 11.2 Figure 11.3

Figure 11.3

The portrait 79.AP.129, Mummy Portrait of a Woman, was instead sold to Alfred Emerson at some point before 1922; the reverse preserves multiple export stamps from the Bundesdenkmalamt of Austria (fig. 11.5).29 Because the sequence of twentieth-century Austrian export stamps can be dated, they offer an underexplored avenue for documenting the dispersal of Graf’s collections.30 This portrait has other unexplained markings, including a number in pencil beginning with “AV” (repeated twice) and another set of numbers—“109/167”—perhaps relating to its sale in 1942 at the Kende Galleries, where it was lot 167.

One unusual example of an unknown stamp, found on the reverse of a portrait from the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, is a square with scalloped edges, perforated in a cross pattern, with an elaborate design in blue and traces of ink (fig. 11.6).31 Although uncommon, this stamp is also identifiable on more modern works of art, including at least one painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder.32 Although the date and purpose of the stamp remain opaque, additional examples may help clarify its identity.

Figure 11.6

Figure 11.6Analyses conducted as part of the APPEAR project suggest other pathways of research that may connect the Getty’s portraits to others on the art market. One is the presence of lithopone, seen in four of the Getty’s panel paintings: the three panel paintings once identified as a triptych (74.AP.20–.22) and a portrait of a man (73.AP.94).33 All four were acquired in 1973 or 1974, and the dates and purposes of any prior restorations were unknown at the time of purchase. Lithopone, a pigment invented in 1874, is a mixture of barium sulfate and zinc sulfide.34 At least two additional portraits in the APPEAR database preserve evidence of lithopone, including a modern forgery and a portrait now in Chicago.35 Is lithopone use indicative of restorers working in a particular time, place, or firm? Additionally, all three panels of the “triptych” have detectable levels of bromine on both sides, suggesting residue from a methyl bromine application for pest control. Future research may help clarify the history of pesticide treatment for ancient panel paintings over the past few centuries.

Given that so many portraits entered into collections over the past century without excavation reports or publication histories, tracing mummy portraits on the market is challenging. Illustrations of mummy portraits in early auction catalogues are rare; terse descriptions—“Three ancient Portraits painted on wood panels, from the Fayum”—paired with unphotographed lots are not uncommon.36 Studies on the reception of mummy portraits are a boon to provenance research, as they aid in tracking changes over time to mummy portrait lot descriptions, which range from Byzantine to Hellenistic, Egypto-Roman, Greco-Egyptian, Greco-Alexandrian, or Coptic, rarely with any specified provenience.37 The ways in which these portraits were and are categorized within market settings reflect changes in contemporary scholastic debates as well as consumer preferences in selecting and ultimately purchasing these objects. Tracing a mummy portrait requires a consideration of how it may have been described, not only how it would be labeled today.

Provenance research has also been aided in recent years by the growing number of dealer and collector archives now available in libraries across the world. Dealer files can help document provenance as well as changes in a portrait’s appearance, its mounting, and more. Among the most relevant for mummy portrait research are the records of the Brummer Gallery and the Kelekian Archives, both housed within different departments at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.38 Dealer advertisements in trade publications, also increasingly available as a digitized resource, can serve as early publications for portraits on the art market. Further, considering historic display choices makes clear the desire to literally reframe mummy portraits within the painting tradition of the European canon. That so many portraits have now been removed from these older frames and mounts for contemporary displays is a further reminder of the changing reception that has greeted mummy portraits over the past two centuries: Are they artifacts? Are they human remains? Are they works of art? These shifting categories are, in turn, reflected in dealer stock books and academic publications, which then affect provenance research.

Reconstructing a History: An APPEAR Case Study

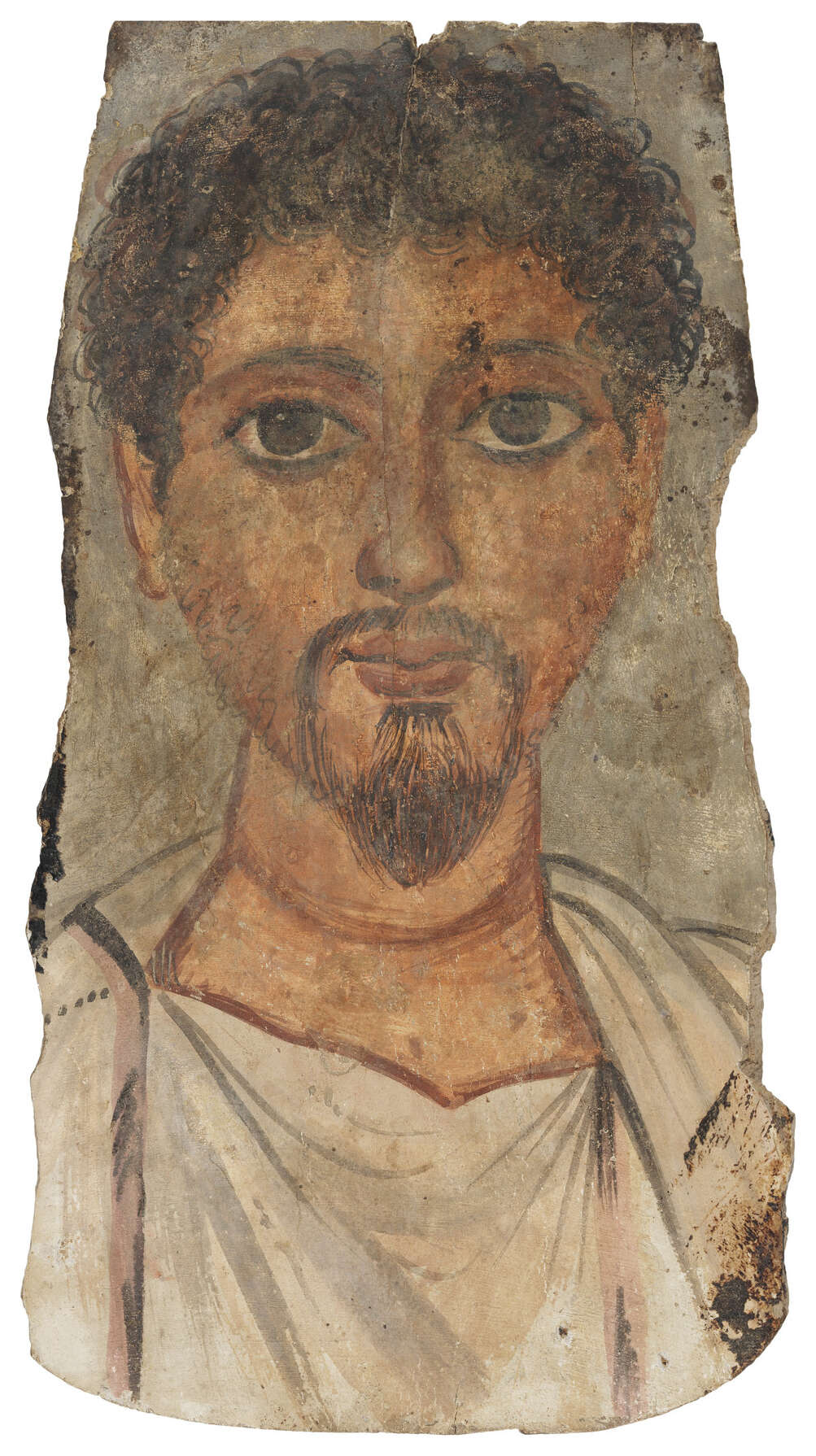

The value of approaching a portrait’s history through both provenance research and conservation analyses can be illustrated by an APPEAR portrait donated to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in 1971 by Phil Berg, a local art collector and talent agent (fig. 11.7).39 The portrait had arrived at LACMA with no prior provenance information, but Marie Svoboda of the Getty was able to identify a Graf stamp on the portrait’s reverse while it was being imaged for the APPEAR project (fig. 11.8). Another stamp was later determined to be an Austrian export stamp, as faint letters reading “Bundesdenkmalamt, Wien” are visible; this stamp probably dates to between 1923 and 1934, congruent with the dispersal after 1930 of the group of portraits owned by Kertzmar. Research for this paper led to an earlier catalogue of Berg’s collection; in this volume the portrait’s photograph shows evidence of an earlier phase of restoration by that time.40 Figure 11.7

Figure 11.7

With confirmation of a Graf provenance, the portrait could then be matched to one published by Parlasca, where a historical photograph of the portrait showed it in a different state of conservation, with dark patches occluding much of the face.41 The portrait’s move to Los Angeles was unknown to Parlasca, who had listed it as unpublished. Additional labels on the reverse of the portrait do not correspond exactly to any others in the APPEAR database, and they may relate to the panel’s conservation history.

An examination of the portrait’s results indicates the presence of zinc white in the clothing and in the hair, a sign of overpainting (fig. 11.9).42 But there are no obvious signs of overpainting or restoration in many of the darkened areas extant in 1930; delicate pigments, like the used to indicate the veins in the corner of the eyes, are evident in the UVF results. Although diagnosis is difficult through photographs, perhaps the blackened areas were the result of burial residue or adhesives; additional research into the panel’s surface is needed to understand the sequence of historical photographs. Research stemming from APPEAR has added decades of evidence about the portrait’s history, but the provenance recovered would not be as valuable without the conservation data, which allow us to begin to understand the changes the portrait has undergone throughout this time. Figure 11.9

Figure 11.9

Conclusion

While provenance may not have been the original goal of the APPEAR project, it allows for the opportunity to explore the multiple, complicated histories of these portraits in collections around the world. Just as understanding the taphonomic processes that artifacts have undergone in archaeological contexts is important for later interpretation of these objects, the physical processes that affect artworks after excavation are imperative to understand as well. Projects such as the APPEAR database underscore the need for dynamic collaborations on provenance as much as on material analyses.

Provenance, as a part of art-historical investigations, can help unravel where a portrait was created or who owned it. Provenance alone does not capture when a portrait was framed, fractured, or restored, although it provides a scaffold on which these data can be pieced together. Likewise, conservation and material analyses are a part of provenance; they contribute toward a greater, holistic understanding of an object’s past. The history of mummy portraits is also inextricably tied to the extraction and marketing of other Egyptian artifacts from the same burial grounds. The provenance documentation in the APPEAR database better contextualizes the broader market for Egyptian antiquities throughout the past two centuries. Every portrait in APPEAR has the potential to inform another: that is the premise and the promise of this project. The continued shared interrogation of the provenances and conservation histories of these portraits around the world is an essential component toward this end.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Marie Svoboda and Mary Louise Hart for their encouragement and assistance with this paper, to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) for use of its image and data, and to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for its support of the conservation science fellow who performed some analytical work on the LACMA portrait.

Notes

- “The APPEAR Project,” accessed November 28, 2018, https://www.getty.edu/museum/conservation/APPEAR/index.html. ↩

- My thanks to David Newbury for this phrase. ↩

- , 48–49. ↩

- . ↩

- Mummies (Organic Material) Child Mummy, Durham University Oriental Museum: DUROM 1985.61; the mummy was previously sold as part of the dispersal of the Pitt-Rivers family collection. For an example in Munich of a once intact, excavated portrait mummy for which only the portrait survives, see , 6. ↩

- , 18. ↩

- The association of style with a presumed findspot is further complicated by the evidence for the transport of portrait mummies prior to burial. , 38–39. ↩

- On the early history of mummy portrait collecting, see , 18–22; ; , 4–5. ↩

- ; on the history of Graf’s varied collections, see and , 217. ↩

- , 2; , 192–95, 214. ↩

- , 27–28; . ↩

- On Petrie’s excavations, see , xvi–xvii; on his mummy portrait finds, see . ↩

- . In addition to the fragments published here, a male portrait, acquired in July 1888 from Petrie, can be added to those works probably on display at Rushmore. ↩

- , 102. ↩

- Pitt-Rivers’ own guide notes that one or more of the portraits on view were “obtained by Mr. Flinders Petrie in Egypt,” while omitting any additional provenance or excavation information. See , 8. ↩

- , 5; , 35–37. ↩

- , . ↩

- I would like to thank all involved for their invaluable contributions. ↩

- , 69. ↩

- , 29. ↩

- , 35–36; , 28–29. ↩

- “EA6713,” British Museum, accessed July 21, 2018, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=129371&partId=1&searchText=henry+salt+6713&page=1; “Mummy Portrait of a Young Woman,” 2009.16. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, accessed July 21, 2018, https://emuseum.mfah.org/objects/96231/mummy-portrait-of-a-young-woman. Additional portraits in the database are on loan to APPEAR institutions from private collections. ↩

- “Funerary Shroud,” 72.4723 and 72.4724, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, accessed May 20, 2017, https://www.mfa.org/collections/object/funerary-shroud-136783 and https://www.mfa.org/collections/object/funerary-shroud-136779. ↩

- It is hoped that APPEAR entries will include these whenever possible, especially for stickers or stamps no longer extant but visible in archival photographs. ↩

- , 29. ↩

- For their complete provenances, “Mummy Portrait of a Woman,” 79.AP.129, J. Paul Getty Museum, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/8633/unknown-maker-mummy-portrait-of-a-woman-romano-egyptian-ad-175-200/; “Mummy Portrait of a Young Woman,” 81.AP.29, J. Paul Getty Museum, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/9400/unknown-maker-mummy-portrait-of-a-young-woman-romano-egyptian-about-ad-170-200/. ↩

- , 34; for the use of this stamp on collections beyond mummy portraits, see , 125–27. ↩

- Fragment of a Portrait, APM 8654, Amsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum. ↩

- This distinctive triangle stamp dates from April 1939 to November 7, 1940 or 1942; many thanks to Anita Stelzl-Gallian of the Bundesdenkmalamt for this information and her assistance. ↩

- These are rarely noted in museum catalogues; , 88, is a notable exception. ↩

- “Portrait of a Man,” 39.025, Providence, Rhode Island School of Design Museum, accessed July 22, 2018, https://risdmuseum.org/art-design/collection/portrait-man-39025?return=%2Fart-design%2Fcollection%3Fsearch_api_fulltext%3D39.025%26field_type%3DAll%26op%3D. ↩

- Lucas Cranach the Elder, Portrait of Christiane of Eulenau, 1534, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, accessed April 21, 2018, http://lucascranach.org/DE_BStGS_13706. As with the mummy portrait, this painting also passed through the Galerie Fischer in Lucerne, one possible but unconfirmed connection. ↩

- For an in-depth treatment of 74.AP.20–.22 and their histories, see . ↩

- “Lithopone,” Conservation and Art Materials Encyclopedia Online, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, accessed August 1, 2018, http://cameo.mfa.org/wiki/Lithopone. ↩

- Art Institute of Chicago, 1922.4799; , para 76. ↩

- Sotheby’s, London, 18 October 1949, p. 19, lot 214. ↩

- E.g., the Sotheby’s sale of July 27, 1931, at which both mummy portraits and textiles from the Graf collection were sold. The portraits are described by their provenance (“from the Graf Collection”) and the textiles by a vague provenience (“from Egyptian burial grounds”), as if the portraits alone were dissociated from their original context. ↩

- “The Brummer Gallery Records,” Cloisters Library and Archives, accessed April 12, 2018, http://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/landingpage/collection/p16028coll9. The Kelekian Archive is held by the Onassis Library for Hellenic and Roman Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. ↩

- “Phil Berg, a Pioneer Talent Agent…,” UPI Archives, February 3, 1983, accessed July 28, 2018, https://upi.com/6058577. ↩

- , 32A. ↩

- , no. 915. ↩

- . ↩