12. Painted Mummy Portraits in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

The Collection of Classical Antiquities of the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest owns five painted mummy portraits from Roman Egypt; this essay aims to discuss them in light of recent examinations carried out as part of the APPEAR project.1 Over the past few years, valuable new information has been revealed via both restoration and technical analyses performed in cooperation with the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, under the direction of Bettina Vak, and through research on the collection history of the five pieces—as well as a sixth portrait from a private collection that for a short while was deposited in the museum. This paper concentrates on collection history, which sheds light on important aspects of the portraits—such as , condition, and the date of their reworking—and also deals with specific features of private and, subsequently, public collecting. These concerns may be quite different from those encountered in larger museums and as such are lesser discussed perspectives in the highly topical debate on “who owns antiquity.”2

The of the five Budapest portraits is not known: we have presumed findspots for all of them but no information on their archaeological contexts. All have been stripped of their immediate contexts—that is, the mummy casings into which they were presumably inserted. We do not know to whose burials they once belonged, and we have scant information on where the patrons lived as well as when and how the deceased were buried. Without their names, an essential part of their identity, what survives is a constructed image—one that is heavily altered through the removal of layers of bandages and and through the addition of modern layers of paint that may completely obscure the original image. In evaluating the five mummy portraits, we are left with the objects as they are today and can rely on few outside sources to complement our findings.

The paintings themselves are funerary portraits in the Greco-Roman sense, constituting a pictorial record of the deceased with a focus on their position within contemporary society: the commemorate their subjects as members of the Romanized Egyptian elite.3 It is the Greco-Roman aspect that dominates the appearance of the Budapest portraits today: save for barely noticeable hints, like traces of linen and resin,4 little evokes the context of the paintings within Pharaonic burial practices. In the Egyptian funerary religion, however, the portraits are detached accessories of mummified figures, which, once fitted closely above the face, served as substitutes for the head, aiding the returning spirit in identifying the body and enabling it to partake of the funerary offerings.5 Through the sacred wrappings, the , and the , the paintings did not so much represent the deceased as humans but signaled their transformation into gods. Like the wrapped bodies themselves, the mummy portraits inserted within the linen bandages were meant to be hidden inside the tomb, safe from desecration—being locked away and covered ensured their preservation. To the ancient Egyptian mind, the paintings in Budapest, like hundreds of other mummy portraits similarly detached and dispersed around the world today, would represent failures in the process of self-preservation.6

With little awareness of this loss, the public and the scholarly community have been fascinated by these remarkably lifelike and vivid representations since the large-scale discovery of the corpus in the late nineteenth century. Given the cross-cultural context of their creation in Roman Egypt and the complexity of their function within that culturally variegated milieu, the paintings are open to several complementary investigative approaches and multiple layers of interpretation, which also allow for various possibilities in their display. In the new permanent exhibition Classical Antiquities at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, we chose to display two paintings (figs. 12.1 and 12.2) in a room focused on concepts that may offer direct points of connection to visitors today.7 The paintings appear together with funerary portraits from other periods and cultures, illustrating how people of antiquity perpetuated the memory of their loved ones. No attempt is made at reconstructing the lost Egyptian context of the mummy portraits, and there is a conscious refraining from pretending that such a reconstruction could make up for the loss of that context. The paintings are not presented as extensions of the body, in their aspect of soma, to paraphrase Jan Assmann,8 but in their quality as sema—as signs or records of the lives of people of the past.

Prior to this installation, all five Budapest portraits underwent cleaning and stabilization. This restoration was performed by Bettina Vak at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, where the paintings were transported in late 2015. Also carried out were technical studies that enabled , , and wood identification, and that complemented art-historical investigations.9 Brief references to the results will be made below as the portraits are discussed in the light of their collection history. The five portraits have not only lost their ancient context—we are also in the dark about most of their modern history. In the following sections, we attempt to reconstruct the little that we could gather about the fate of the paintings at the end of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century. Information on the lives of their three collectors offers new insights on the objects themselves and also outlines three different paradigms in the social history of modern Hungary.

Mummy Portraits from the Collection of Bernát Back

The two portraits now on display were purchased by the Museum of Fine Arts from Bernát Back, a Hungarian art collector, in 1948.10 Back was born in 1871 into a Moravian Jewish family that had settled in Hungary in the mid-nineteenth century.11 The family quickly became integrated into Hungarian society, with Back’s father receiving noble titles and Bernát himself entering the political elite as a member of the Upper House of the Parliament. He lived in the city of Szeged in southern Hungary as a successful businessman and a prominent art patron, amassing a large and valuable collection of mostly sixteenth- to seventeenth-century paintings and sculptures.12 Back sought to make his collection accessible to the public, a goal that was eventually realized in 1917 with an exhibition at his Szeged home; a subsequent show of his later acquisitions was also mounted there two decades later, in 1938. Back, having moved to Budapest, used what was left of his political influence and connections with the Catholic Church to survive the Second World War unharmed, a rare exception in the shared destiny of Hungarian Jews. He stayed in Budapest until 1951, when he was forced to flee to avoid retaliation by the Communist government for his earlier support of the right-wing regime that had propelled Hungary to its grim role in the war and that was largely responsible for the fate of Hungarian Jews. He spent his last years with his daughter’s family in Gyón, a small town near Budapest, where he died in 1953.13

Like other members of the contemporary Hungarian elite, Back had little interest in ancient works of art: it was the Middle Ages, the era of a great, independent kingdom, that was generally elevated to the mythical status of a golden age in Hungarian cultural memory.14 But Back had a particular enthusiasm for Egypt: in 1914, he sponsored as well as took part in a scientific expedition to the Monastery of Saint Catherine on the Sinai Peninsula with a team that included the renowned Coptologist Carl Schmidt and the orientalist Bernhard Moritz.15 The outbreak of the First World War interrupted the mission, and much of the scientific documentation was lost.16 Back’s photographs and meticulous notes, however, survived, and he continued to work on this material up until his death four decades later.17

We have only one source concerning Back’s antiquities that may shed light on his attitude toward ancient art. His correspondence from 1905 shows that he owed his collection of antiquities, including a group of funerary masks, to his friend the painter and art collector Sigmund Röhrer, who purchased the pieces from Theodor Graf for an unusually low price. Röhrer was quick to acquire the masks—in the hopes of Back’s subsequent approval—before the German Egyptologist Friedrich Wilhelm von Bissing could make an offer.18 This turned out to be more than just a good business opportunity, as Back decided to keep the pieces; the masks were only purchased by the Museum of Fine Arts from his grandson in the 1970s.19 Interestingly, the items then numbered twenty-two, though Röhrer’s letter from 1905 mentions only twenty-one, which means that Back must have bought antiquities, including the two painted mummy portraits, on other occasions as well. The stamps on the backs of the portraits clearly show that they too come from the Graf Collection.20 It is probably because of this Graf connection that the two portraits are presumed to have come from in the ; in Back’s documents there is no indication about their origin. The two portraits actually look quite different.

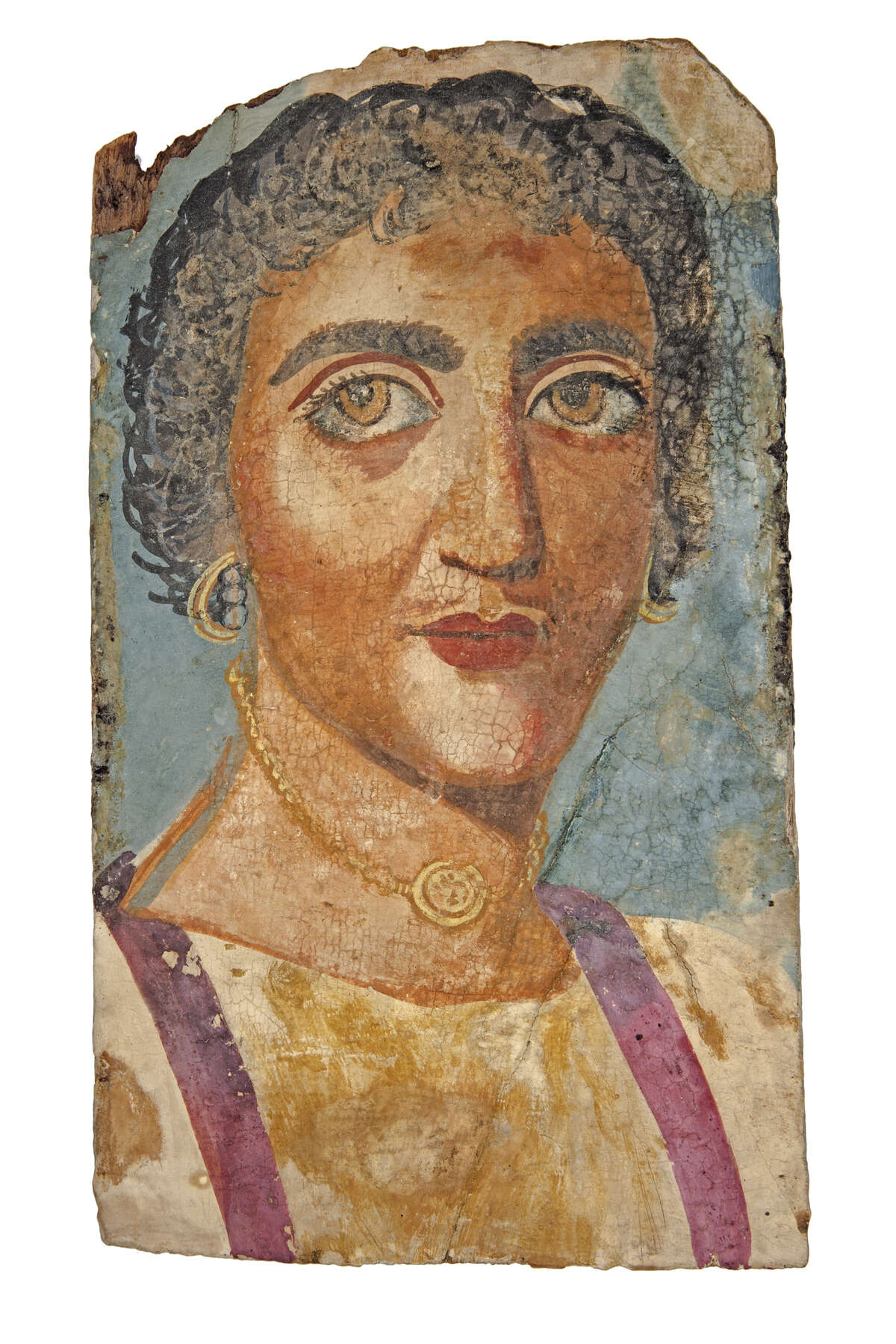

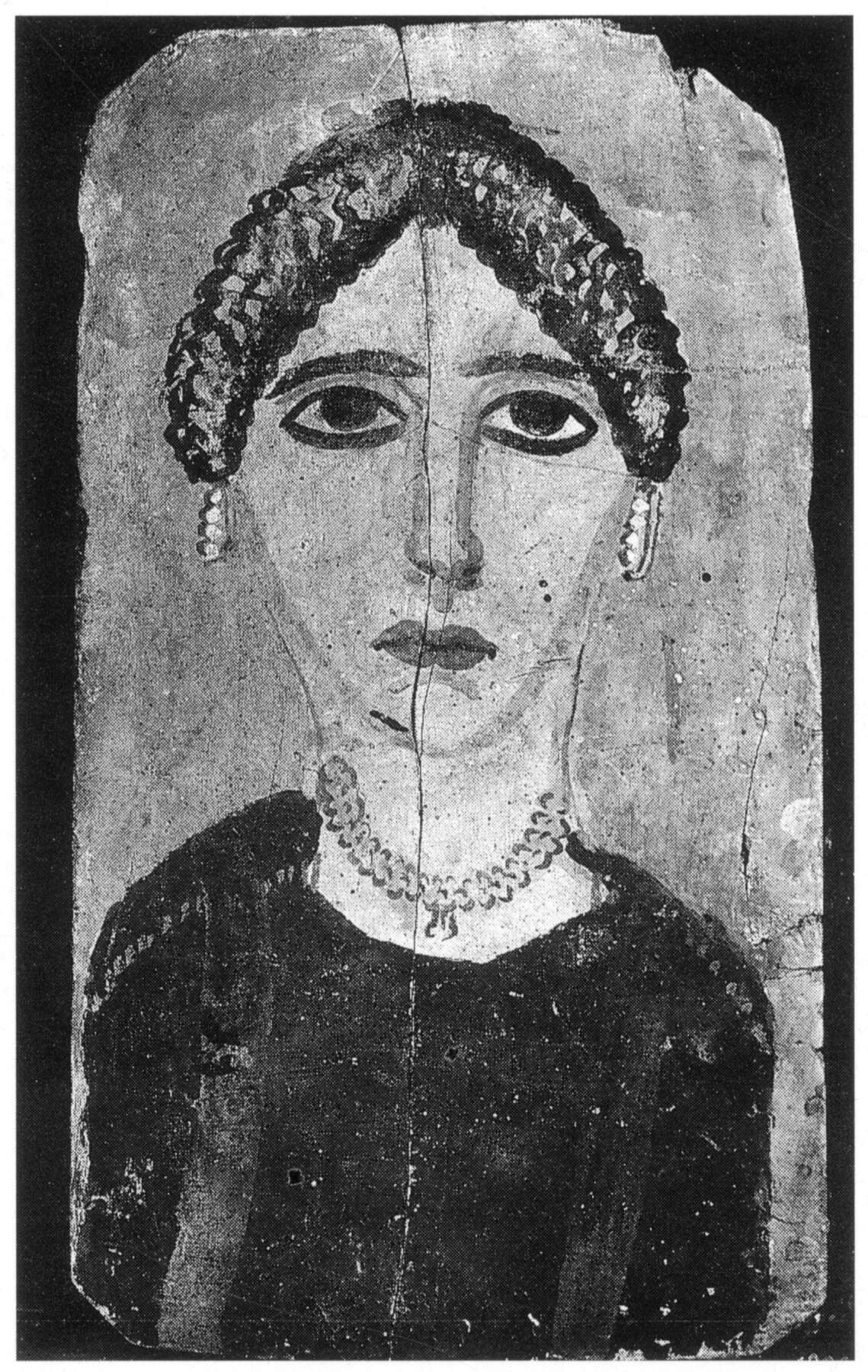

The first one is an painting on a thin panel of lime wood. The image shows an elderly woman with graying hair; she wears a purple with black and no jewelry (see fig. 12.1). Based on the hairstyle, the portrait has been dated to the .21 The other portrait22 was painted in on a thick sycomore fig panel; resin stains are found on the perimeter of the painting on both sides (see fig. 12.2). Against a blue background there is a woman wearing an off-white tunic with purple clavi, a pair of hoop earrings with three pearls each, and a necklace with a gorgoneion pendant.23 In many ways this portrait is strongly Hellenized, with effects of foreshortening, eyes gazing off to one side, and right shoulder raised slightly higher than the left. At the same time, the execution does seem rather hurried, as if the artist did not entirely feel comfortable in this visual language. Figure 12.1

Figure 12.1 Figure 12.2

Figure 12.2

The clavus on the left shoulder seems a bit too thick, whereas on the right shoulder the tunic’s neckline actually cuts into the clavus. There is a thick blue-gray line next to the right side of the neck, which suggests either a misunderstanding of the garment or an attempt to make the neck look thinner without changing the outline of the tunic. Similarly awkward is the right earring, which appears as if it did not actually pierce the ear; rather, it floats directly in front of it. Much of the left earring is covered by hair. The coiffure itself is problematic: with its short, free locks and lack of a parting, it does not conform to typical styles of the period. The portrait was dated to the third quarter of the fourth century by Klaus Parlasca and to the by Barbara Borg; the latter dating is generally accepted today.24 We have no close parallels for the piece;25 the unique hairstyle may perhaps be explained by the possibility raised by Susan Walker at the Getty conference—that the painting was reworked in antiquity, turning the portrait of a man into that of a woman when the need arose.

Mummy Portraits from the Collection of Bonifác Platz

Three other portraits entered the Museum of Fine Arts only two years after the Back pieces, in 1950, but their collection history outlines an entirely different situation. The works were purchased in Egypt by a Cistercian monk and scholar, Bonifác Platz.26 Platz was born into a German artisan family in 1848, in the city of Székesfehérvár in central Hungary. He was a first-generation intellectual who became a priest, a teacher and theologian, and an ardent critic of the theories of Charles Darwin. Platz published widely on the age, origin, and history of mankind, and some of his works even appeared in German and Polish.27 Fascinated by ancient Egypt, he traveled to the Nile valley six times between 1896 and 1908. The first excursion was an official one: together with Ignác Goldziher, the eminent orientalist of the time, he led a six-week study trip, visiting the Nile valley from Alexandria to Philae. On his later trips during the first years of the twentieth century, Platz purchased several Egyptian antiquities, which he later deposited at the Cistercian abbey at Zirc. After his death in 1919, the objects disappeared for decades, then resurfaced in the 1950s and were obtained by the Museum of Fine Arts in subsequent years. Many key pieces in the museum’s Collection of Egyptian Antiquities come from Platz’s purchases, and the museum’s classical collection also includes many different artifacts from his acquisitions.

An amateur Egyptologist, Platz compiled a detailed manuscript catalogue of his collection of more than 150 pieces, and this record contributes considerably to what we know about the portraits.28 The catalogue gives a thematic arrangement of the objects, but the numbers follow an approximate order of their acquisition between 1896 and 1908. This sequence suggests that the three portraits were purchased on two separate occasions.

The earlier acquisition bears the number 73 in the catalogue and purports to be from Akhmim in Upper Egypt (fig. 12.3).29 We do not know if this should be taken as a place of purchase or as information Platz obtained from the seller; the phrasing suggests that the latter is more likely, because otherwise Platz seems to have carefully marked what he bought on-site and what he found in situ. The information may still be important as an independent source that could be compared with the archaeological data. Like all the Platz portraits, the image is painted on a thin lime wood panel in the encaustic technique, and it shows a woman wearing a purple tunic with a black clavus, adorned with a pair of simple hoop earrings; the turbanlike hairstyle would suggest a second-century date. This painting’s authenticity has never been questioned, even though large-scale retouching is quite visible. analysis confirmed the modern retouching as well as indicated the presence of small traces of the original and pigments. Recent X-ray images have revealed the extent of modern retouching even more clearly, by outlining an entirely different face beneath the modern layer.30 Figure 12.3

Figure 12.3

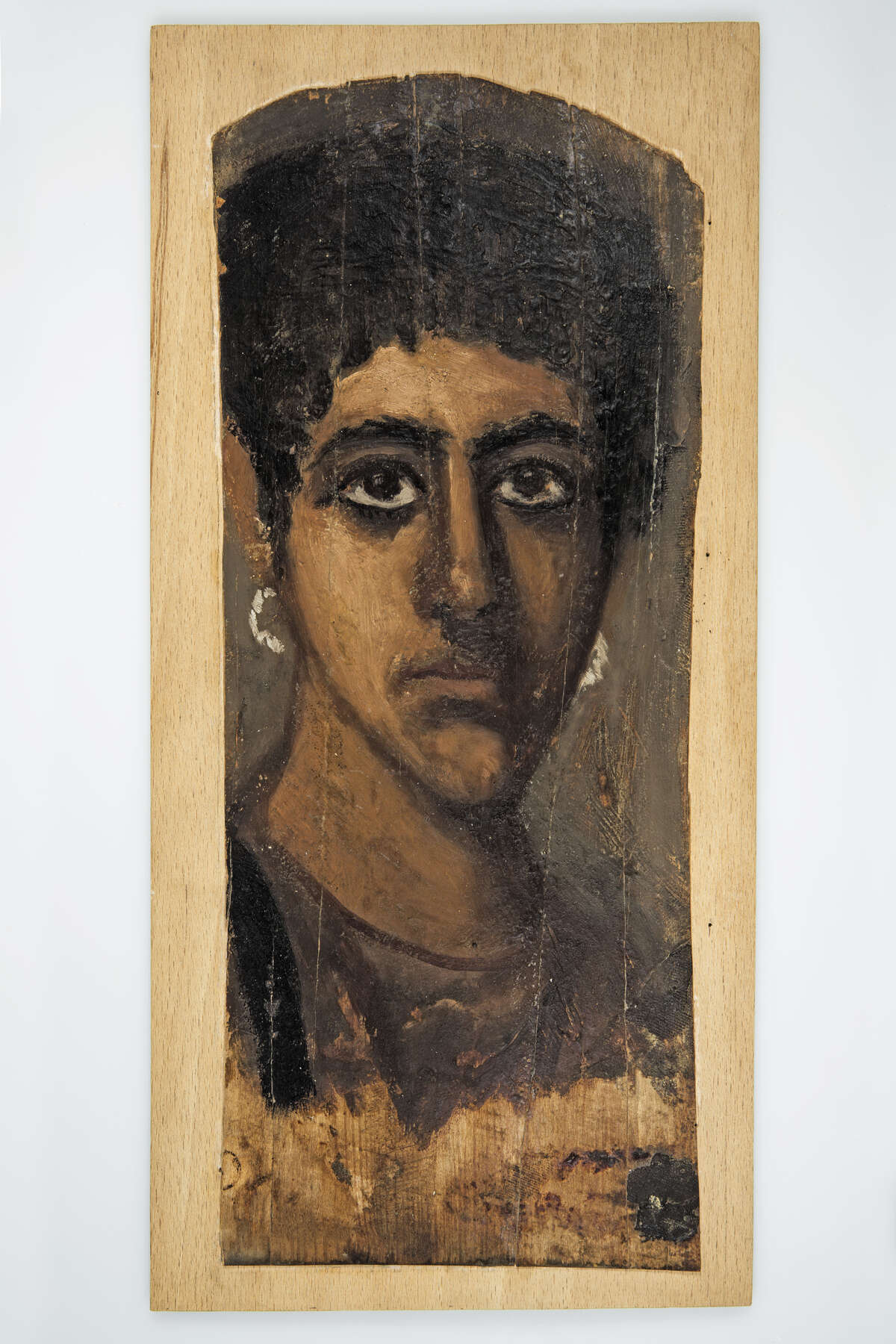

Heavy retouching is also evident in the case of another painting from the Platz collection. The Mummy Portrait of a Man (fig. 12.4)31 was dismissed by Parlasca as a modern forgery, but XRF analysis has here too demonstrated traces of the original ground and pigments in the area of the right eye. The portrait bears the number 117 in the Platz catalogue and is said to be from the Fayum. It is important to note that Platz himself lamented that the value of the painting was reduced by the heavy retouching, which suggests that these considerable restorations were carried out by trained painters in Egypt prior to his purchase at the turn of the nineteenth century. Figure 12.4

Figure 12.4

The third portrait from Platz’s collection is reassembled from seven fragments of lime wood, which have been fastened on to a wooden board (fig. 12.5).32 It shows a young woman, her head turned slightly to the right, wearing a purple tunic and a gold necklace threaded with red beads and dark, rectangular stones. Microscopic images and XRF analyses have shown what was only suspected before: that there is gold foil on the jewelry, lips, and eyes. The hairstyle suggests a date. Figure 12.5

Figure 12.5

Whereabouts Unknown: A Mummy Portrait from the Collection of Oszkár Hillinger

At present, we are still in the dark about the fate of the sixth mummy portrait that surfaced in Hungary in the mid-twentieth century. The portrait was owned by Oszkár Hillinger, whose biography can only be partially reconstructed.33 He was born in 1887, in the city of Eger in northeastern Hungary, into a Jewish family. He went on to become a successful businessman and a high-ranking bank clerk in Budapest, and he survived the Second World War only to be relocated to the small town of Jászkisér in the early 1950s as an “enemy of the working class.” He later emigrated to London, where he is presumed to have died in 1962. Not much is known about the artworks in his possession, though they included sculpture, furniture, and a collection of about five thousand ex libris created for him by artists from Hungary and abroad. Apart from the mummy portrait in question, we do not know of ancient works of art in his possession; like Back, Hillinger did not focus on collecting antiquities.

We owe both the information on and the photograph of this portrait to an exhibition organized in fall 1947 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, which was still partly in ruins after World War II.34 The exhibition brought together antiquities in Hungarian private collections: approximately five hundred items, including Hillinger’s painting, were displayed in the museum’s entrance hall. The 35-centimeter-tall portrait, painted in tempera on a panel that was obliquely cut along all corners, shows a young woman with a serious expression; she faces front and wears a red tunic with large clavi, a gold necklace with a small pendant in an inverted T-shape, and gold earrings with four pearls each (fig. 12.6). The portrait is also from Theodor Graf’s collection and was auctioned in Vienna in 1932; thus, the work is presumed to come from er-Rubayat.35 Figure 12.6

Figure 12.6

Museum archives attest that when Hillinger was relocated to Jászkisér in the 1950s and his art collection confiscated by the Hungarian government, the mummy portrait was deposited in the Museum of Fine Arts for safekeeping. Before Hillinger left the country, he bequeathed his collection—or, more precisely, the task of reclaiming his objects from the state—to his sister, Erzsébet Hillinger. It was a lengthy process that dragged on for a decade: the portrait was only returned in 1963. János György Szilágyi, keeper of the Collection of Classical Antiquities at the Museum of Fine Arts then and for the next three decades,36 made several attempts at acquiring the portrait from Hillinger’s heirs, but to no avail. Neither Szilágyi nor Parlasca could later locate the piece, which thus remains inaccessible to both scholars and the wider public.

The primary means for enlarging the Collection of Classical Antiquities in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, has always been the acquisition of objects from private collections in Hungary.37 The three stories outlined above—that of the philanthropist art collector Bernát Back, the scholar and traveler Bonifác Platz, and the art lover Oszkár Hillinger—are emblematic examples of antiquities collecting in Hungary. They represent a tradition in antiquities collecting that resists the labels of both nationalism and colonialism, reflecting instead a humanist attitude that sees Hungarian culture within a shared European tradition and that is driven not by politically motivated institutions but by individuals who recognize the role that antiquity plays in their own culture. In this way, they offer what may be a third approach to the question of who owns antiquity.

These private collections have played a fundamental role in the formation of today’s public collections. At the same time, the story of Oszkár Hillinger also shows the dangers of loss associated with private collecting; perhaps renewed research and the possibilities offered by the APPEAR database will prove helpful in locating the portrait in the future. Once commissioned, painted, wrapped, remembered, and forgotten, then rediscovered, unwrapped, traded, stored, and restored, the portraits continue their long history.

Notes

- See the APPEAR project’s webpage at https://www.getty.edu/museum/conservation/APPEAR/index.html. The APPEAR database gathers information retrieved from portraits dispersed in museums around the world. It encourages joint research and rescues lesser-known pieces from oblivion by placing them into mainstream scholarship, both of which are important factors in the case of the Budapest portraits. We thank the editors for inviting us to read this paper at the conference and for publishing it in the present volume. ↩

- The question naturally echoes the title of James B. Cuno’s monograph Who Owns Antiquity? (). ↩

- For an approach of “deconstructing” the Roman element in mummy portraits, see . Portraiture in Roman Egyptian funerary art is discussed in detail in , esp. 95–174. ↩

- Resin stains appear on fig. 12.1; linen is attached to the board of fig. 12.3. ↩

- Much of what the ancient Egyptians would have considered essential for a continued existence after death is thus lost: besides the qualities and the knowledge necessary to navigate the underworld and to prove victorious before the netherworld tribunal, as well as the provisions from the world of the living, the central element would have been a burial that kept earthly remains and funerary equipment intact so as to accommodate the needs of the transfigured spirit. For a starting point in the vast literature on ancient Egyptian mortuary religion, see ; for an analysis of funerary beliefs in Roman Egypt, see . ↩

- On the significance of textile wrappings in ancient Egyptian culture, and on approaches of the modern West that tend to focus on the (all too literal) unwrapping of that tradition, see the recent, pioneering study by Christina Riggs (). ↩

- The room is entitled “Introite et hic dii sunt”: Eros, Dionysos, Thanatos. It focuses on the spheres of these three deities, whose presence people today may also experience in an elemental way—just like the people of antiquity. ↩

- Discussing ancient Egyptian portraiture, Assmann differentiated between the portraits’ focus on the “body” (soma) and the “sign” (sema), arguing that some Egyptian statue types, such as reserve heads from Old Kingdom burials, were not meant to communicate or commemorate something as signs but instead served as extensions of the mummified body itself; compare , esp. 61‒63. In their Egyptian context, painted mummy portraits would also have been seen as extensions of the body. ↩

- Multispectral imaging was conducted by conservation scientist Roberta Iannaccone, complementing the images taken by András Fáy (Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest). Pigments were identified through micro X-ray fluorescence analysis by Katharina Uhlir (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna); wood samples were collected and analyzed by wood scientist Caroline Cartwright (British Museum, London); X-ray images were later taken by Mátyás Horváth (Hungarian University of Fine Arts, Budapest). We are grateful for the cooperation and assistance of all researchers involved. ↩

- On the acquisition, see , 160–61, 161n473. ↩

- A brief biography is given in , 87. The article, which has a German summary on page 113, provides a comprehensive overview on the history of Back’s collection. ↩

- Many of these today constitute highlights in the Galleries of Old Master Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest: some of them were donated by Back, others were later acquisitions (see ). ↩

- On Back’s final years, see . ↩

- On medievalism in Europe in the nineteenth century, see the studies in . ↩

- On the Sinai expedition, see , 108–12. ↩

- Besides two brief reports by Carl Schmidt and Bernhard Moritz, only one scientific publication survives by the latter: . ↩

- See , 112. The unpublished manuscript is preserved in a private collection. ↩

- Sigmund Röhrer’s letter to Bernát Back on February 8, 1905, mentioned by , 108n164. ↩

- Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts, Collection of Classical Antiquities, inventory nos. 74.2.A–.19.A, 74.45.A, 79.7.A–.9.A. For a recent analysis of the stucco masks, see . ↩

- This was not the first attempt to bring the Graf portraits to Hungary. Graf made an offer to sell some of his portraits to Hungary, and consequently, in March 1891, the director of the National Picture Gallery in Budapest made a proposal to the Hungarian minister of religion and education asking him to consider that the gallery widen its scope of collection to include paintings from antiquity. In the case of a positive decision, three male and three female portraits would have been purchased from Graf’s collection, selected from a list of fifteen items. In the end, the acquisition did not go through. See the Museum of Fine Arts archives 64/1891. ↩

- Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts, inv. no. 8901, 29.5 x 14.1 cm, lime wood. All wood identifications are by Caroline Cartwright. , 60; , 34, no. 269, pl. 65.2; , 30, 191, no. 27; , 46–47, pl. 64.1; , 175, no. 75. ↩

- Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts, inv. no. 8902, 32 x 18.4 cm, sycomore fig. , 60; , 59, no. 642, pl. 152.1; , 195, no. 99; , 55. ↩

- On this type of pendant and its apotropaic function, see , 169n147, as well as . ↩

- See , 59, followed by , 195 versus , 55, and similarly . ↩

- It is not entirely unlike a painting in the Getty Museum (inv. no. 81.AP.29), also from the Graf Collection and also tempera on a thick sycomore fig panel, in which the execution of the mouth, the eyelashes, and the strong contour of the upper eyelid are perhaps comparable, but otherwise the similarities are not very strong. ↩

- For a brief biography, see (in Hungarian). ↩

- See, for instance, Platz , . Platz was not averse to classifying the race of the patrons of his mummy portraits based on their facial features. ↩

- The manuscript is preserved in the Zirc-Pilis-Pásztó and Szentgotthárd Abbey Archives of the Cistercian Order, no. VeML XII. 2/i, manuscripts of Bonifác Platz 9/b. We are grateful to Katalin Anna Kóthay for providing us with a copy of the manuscript. ↩

- Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts, inv. no. 51.343, 39.3 x 16.7 cm, lime wood. Platz manuscript, 23, no. 73; , 60; , 41, no. 297, pl. 71.1; , 48. ↩

- The X-rays were taken by Mátyás Horváth (Hungarian University of Fine Arts) shortly before the closing of this manuscript; the question needs further examination and study. ↩

- Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts, inv. no. 51.342, 28.5 x 15.6 cm. Platz manuscript, 24, no. 117; , 60; , 119n5, pl. 201.3. ↩

- Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts, inv. no. 51.344, 36.5 x 12.7 cm, allegedly from the Fayum. Platz manuscript, 24, no. 118; , 60; , 55, no. 105, pl. 25.3; , 181, 223, no. 121; , 59, 79. ↩

- For a brief discussion of Hillinger’s life and his collection, see . ↩

- , 15, pl. 3. ↩

- , 70, no. 803, pl. 177.6 (dated to the mid-fourth century AD). Based on the sole archival photo, the piece can only tentatively be dated to the second century AD. ↩

- See . ↩

- See , 208. ↩