2. Understanding Wood Choices for Ancient Panel Painting and Mummy Portraits in the APPEAR Project through Scanning Electron Microscopy

Introduction

After the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, Egypt became part of the Roman Empire. In the first through third centuries AD, a new form of funerary artifact—the mummy portrait—became very popular in Egypt. Not only are many of these portraits remarkably realistic depictions of individuals, they also reflect an extraordinary fusion of funerary preferences. The naturalistic style of these works evokes Greco-Roman painting in the Mediterranean area, but they were made to be incorporated into the traditional practice of Egyptian mummification in highly decorated wooden coffins.

In 1995 the British Museum organized a major colloquium on burial customs in Roman Egypt; this was followed in 1997 by the special exhibition Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt, which brought together mummy portraits from many institutions around the world. The exhibition triggered a program of scientific research of mummy portrait wood identification at the British Museum that not only resulted in publications but also continued to inspire collaborative research thereafter.1

Given that I have identified local Egyptian woods for coffins and funerary artifacts in earlier chronological periods, I was surprised to find, from the outset of the research in 1996, that most mummy portraits were made of Tilia europaea (lime/linden) wood—which is not, and has never been, native to Egypt.2 Before the Roman period in Egypt, there had been extensive importation of Cedrus libani (cedar of Lebanon) wood for high-status coffins, but such intensive exploitation of lime wood for (portrait) was an innovation.

Essential Facts about Scientific Wood Identification

Wood anatomy is a recognized specialist area of botanical science; therefore, there are precise taxonomic nomenclature requirements as well as specific protocols inherent to the identification process.3 Fortunately the APPEAR project has adhered to the principles of scientific rigor, applying them consistently to those mummy portraits and painted panels that could be microsampled. This precision resulted in a collaborative corpus of secure scientific wood identifications, which benefit all concerned.

For accurate scientific identification of ancient, historical, and modern woods, preparation of the following three sections is mandatory: transverse section (TS), radial longitudinal section (RLS), and tangential longitudinal section (TLS). For modern and some historical wood samples (particularly those that are not desiccated), wood sectioning coupled with optical microscopy using transmitted (polarizing) light is standard practice, generally on sample sizes greater than those needed for scanning electron microscopy (SEM; see below).4

Wood identification must strictly comply with the International Association of Wood Anatomists (IAWA) protocol, terminology, and numerical feature classification in order to ensure universal comparability of reliable results. This means that each genus or species requires recognition of between forty to sixty predefined characteristics, of which 90 percent are anatomical cellular features. It is important to note that such features can be seen only by examining all three sections (TS, RLS, and TLS), and for this reason it is recommended that a tiny cubic sample is removed, rather than a splinter, as the latter restricts the preparation of a TS.

Mummy Portrait Wood Sampling

Those wooden objects that have survived the particular conditions within ancient Egyptian tombs are remarkable, not least in the level of preservation of their wood anatomy. That said, although the condition of the cellular features is good, the wood may be brittle macroscopically. For that reason, it is preferable to fracture samples of these wooden artifacts in TS, RLS, and TLS (as would be done for charcoal) for microscopical examination, rather than to thin-section them.

At the time of writing (May 2018) thirty-five institutions (from both the pre-APPEAR and APPEAR phases of scientific analysis) have permitted the removal of tiny wood samples for identification. So far, the woods of 180 mummy portraits have been identified by the author, in addition to the woods of twenty nonportrait Egyptian painted panels. This is ongoing research and the numbers grow daily, with numerous samples currently being prepared for identification using SEM. Two different SEM processes are being used: a variable-pressure (VP) SEM, for uncoated wood samples, and a field-emission (FE) SEM, for very high resolution and magnification (up to 300,000x) of ultra-tiny samples that require coating by gold or platinum or palladium to avoid the surface charging that results from the electron beam’s interaction with the wood.

When sampling mummy portraits or painted panels, the following should be avoided:

wood with consolidant or adhesive;

wood that has been affected by rot or insect or fungus attack;

areas of wood with knots or burls, and areas with nails, nail holes, labels, signatures, or saw or drill marks; and

areas of paint, decoration, , or other surface modifications, such as heavy patination.

Sometimes it is possible to sample from the back or underside or from a damaged edge, although it is important to avoid the areas designated above. If frames, dowels, tenons, repairs, or additions are present, it will be necessary to sample these various elements as well, as different woods may have been selected to create them. With the use of high-specification SEM for the wood identifications, I can accept cubic wood samples of 1 millimeter in size (although if samples of 2 to 3 millimeters are permitted, those are preferred). Because specific recommendations for packing, international mailing, and sending by courier are subject to change, participating APPEAR institutions should contact me for regularly updated instructions.

Wood Identification Results: The Current Status

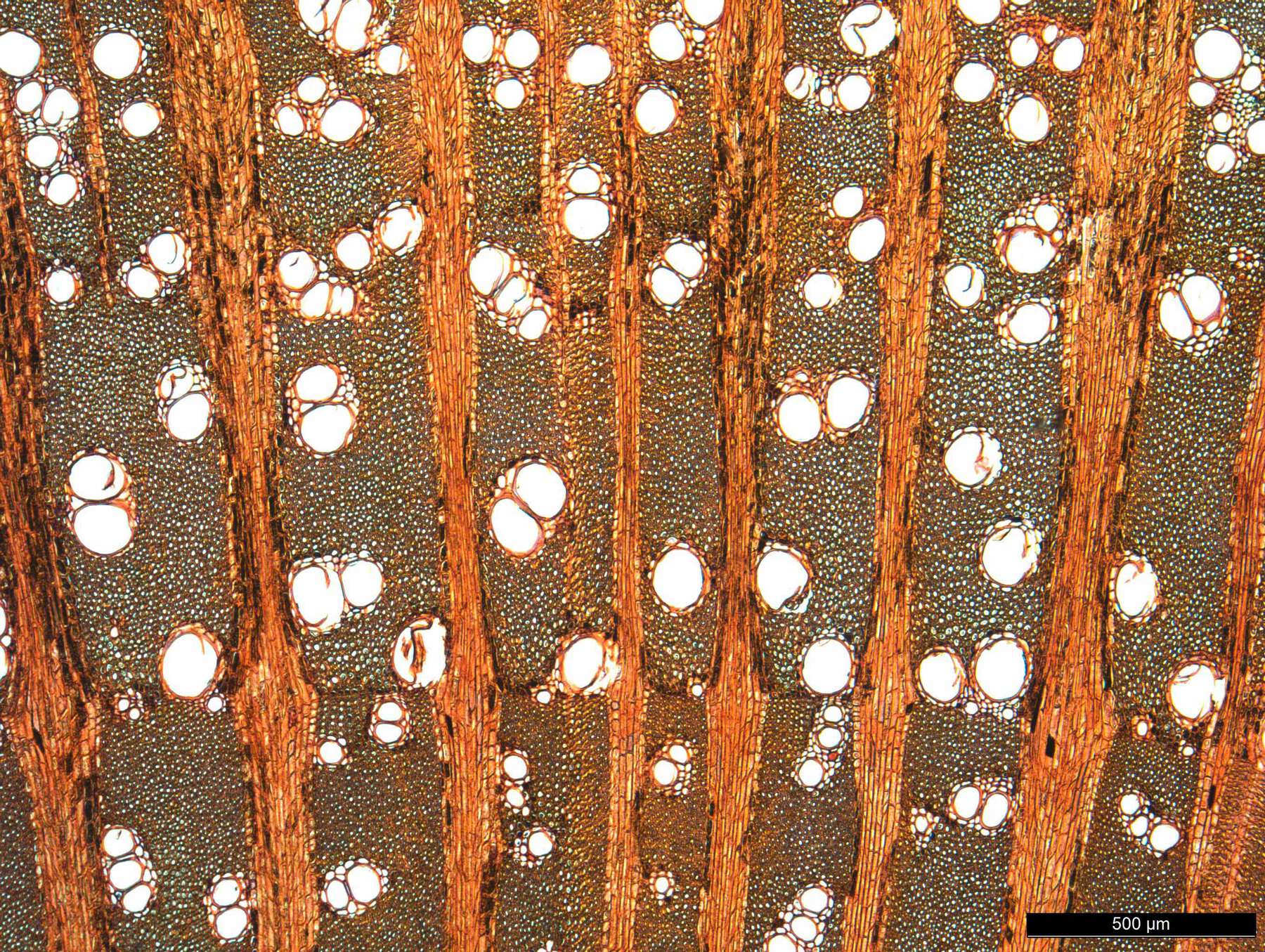

Figure 2.1 shows the current status of mummy portrait and nonportrait panel wood identification results, as of May 2018. The range of woods utilized has been extended, particularly in terms of the use of native woods such as sidr (Ziziphus spina-christi), at 3.1 percent, especially (but not exclusively) for nonportrait painted panels. Tamarisk (Tamarix aphylla), another native Egyptian timber, is represented in small quantities at 1.9 percent of the overall total. By far, the most frequently used native timber is the local fig wood (Ficus sycomorus; fig. 2.2), with 15.6 percent of the total. Five imported European woods are present, dominated by lime wood (Tilia europaea; fig. 2.3), at 69.4 percent; followed by oak (Quercus sp.), at 4.4 percent; cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani; fig. 2.4), at 2.5 percent; fir (Abies sp.), at 1.9 percent; and yew (Taxus baccata), at 1.2 percent. This means that imported European species make up 79.4 percent—principally lime wood, at 69.4 percent—whereas only 20.6 percent are native Egyptian species—principally fig, at 15.6 percent.

Genus | Species | Common Name | Native to Egypt? | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Tilia | europaea | lime, linden | NO | 69.4 |

Quercus | sp. | oak | NO | 4.4 |

Cedrus | libani | cedar of Lebanon | NO | 2.5 |

Abies | sp. | fir | NO | 1.9 |

Taxus | baccata | yew | NO | 1.2 |

Ficus | sycomorus | sycomore fig | YES | 15.6 |

Ziziphus | spina-christi | sidr, Christ’s thorn | YES | 3.1 |

Tamarix | aphylla | tamarisk | YES | 1.9 |

Genus | Species | Common Name | Native to Egypt? | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Tilia | europaea | lime, linden | NO | 69.4 |

Quercus | sp. | oak | NO | 4.4 |

Cedrus | libani | cedar of Lebanon | NO | 2.5 |

Abies | sp. | fir | NO | 1.9 |

Taxus | baccata | yew | NO | 1.2 |

Ficus | sycomorus | sycomore fig | YES | 15.6 |

Ziziphus | spina-christi | sidr, Christ’s thorn | YES | 3.1 |

Tamarix | aphylla | tamarisk | YES | 1.9 |

Figure 2.2

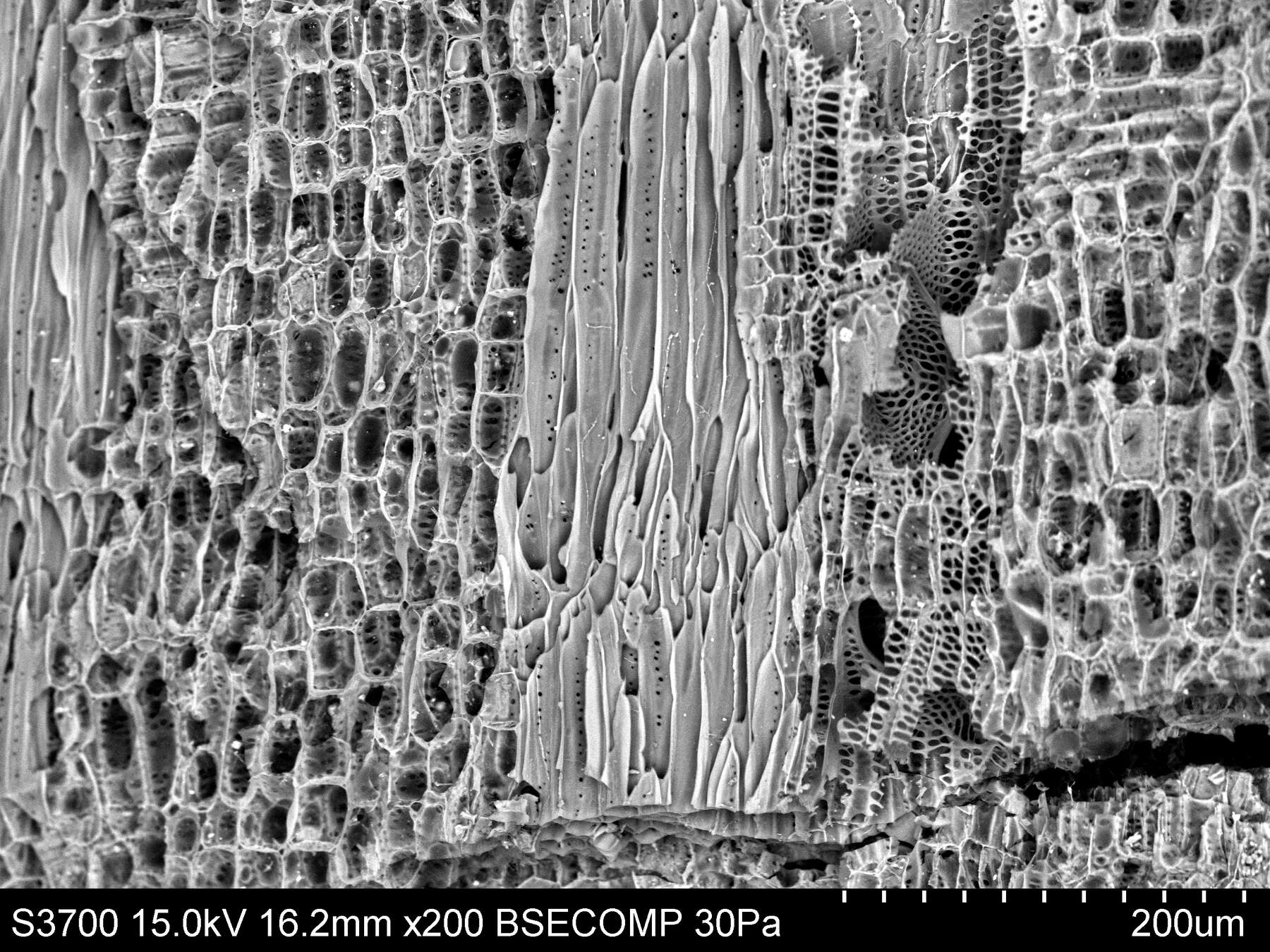

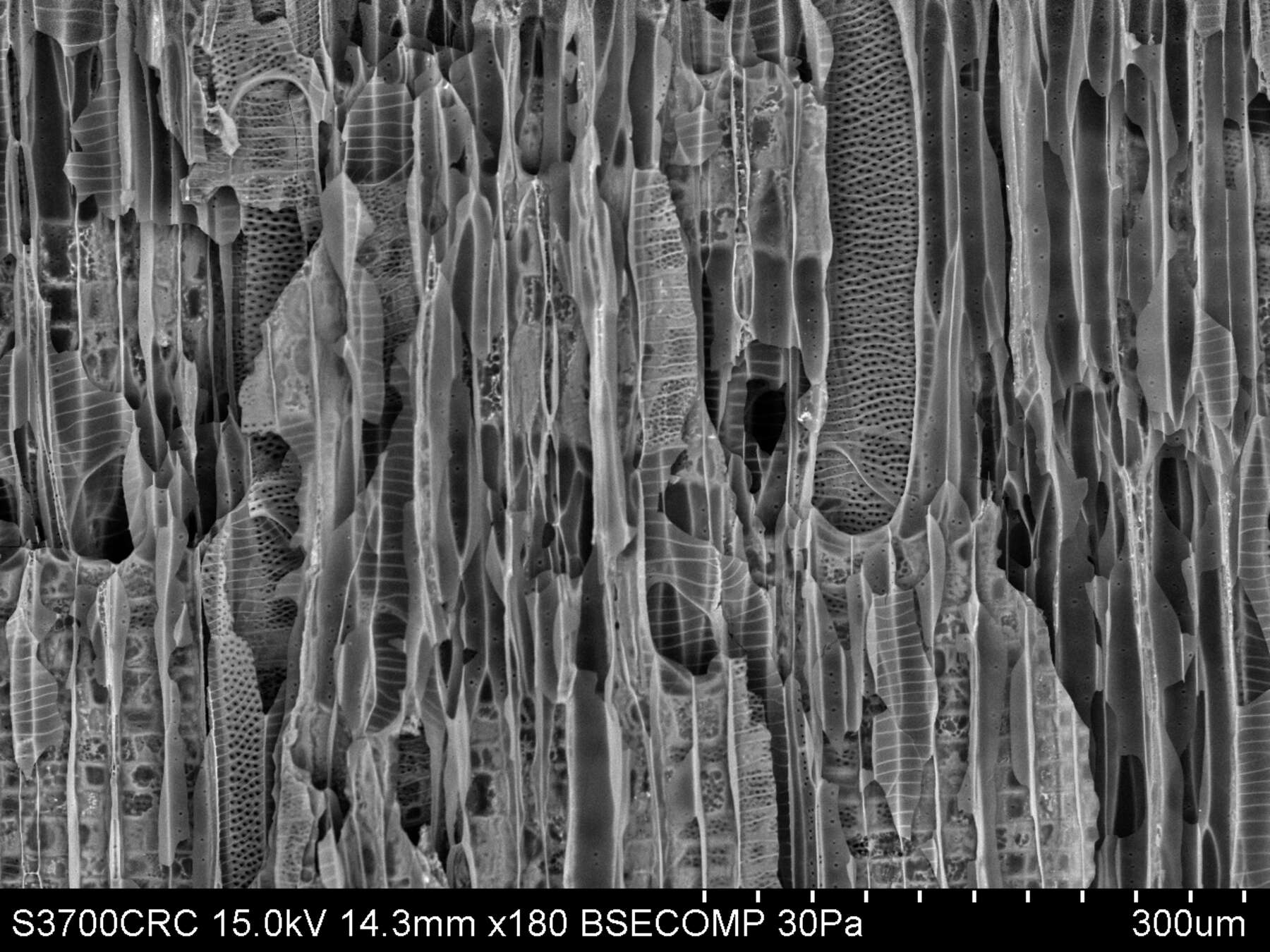

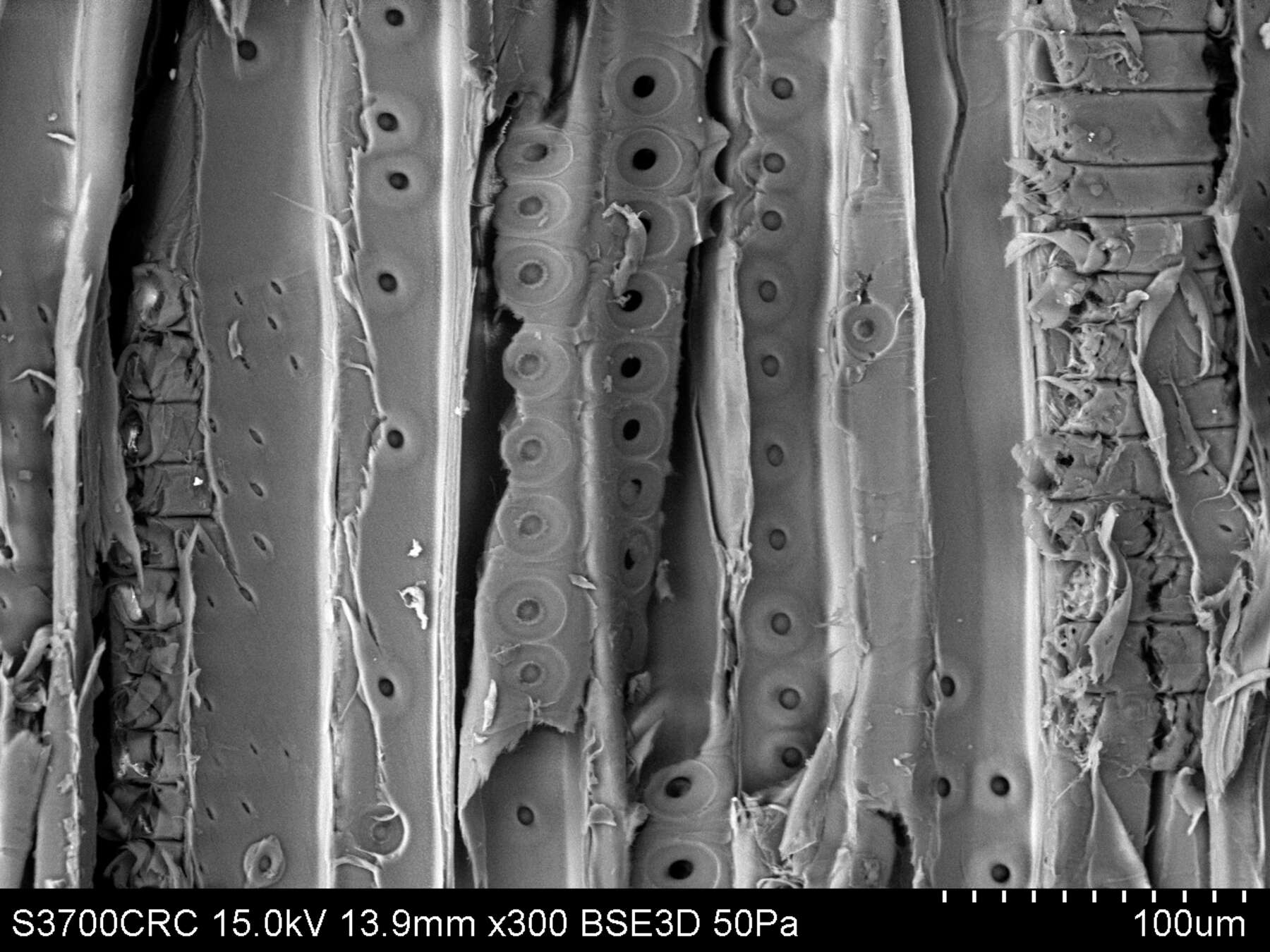

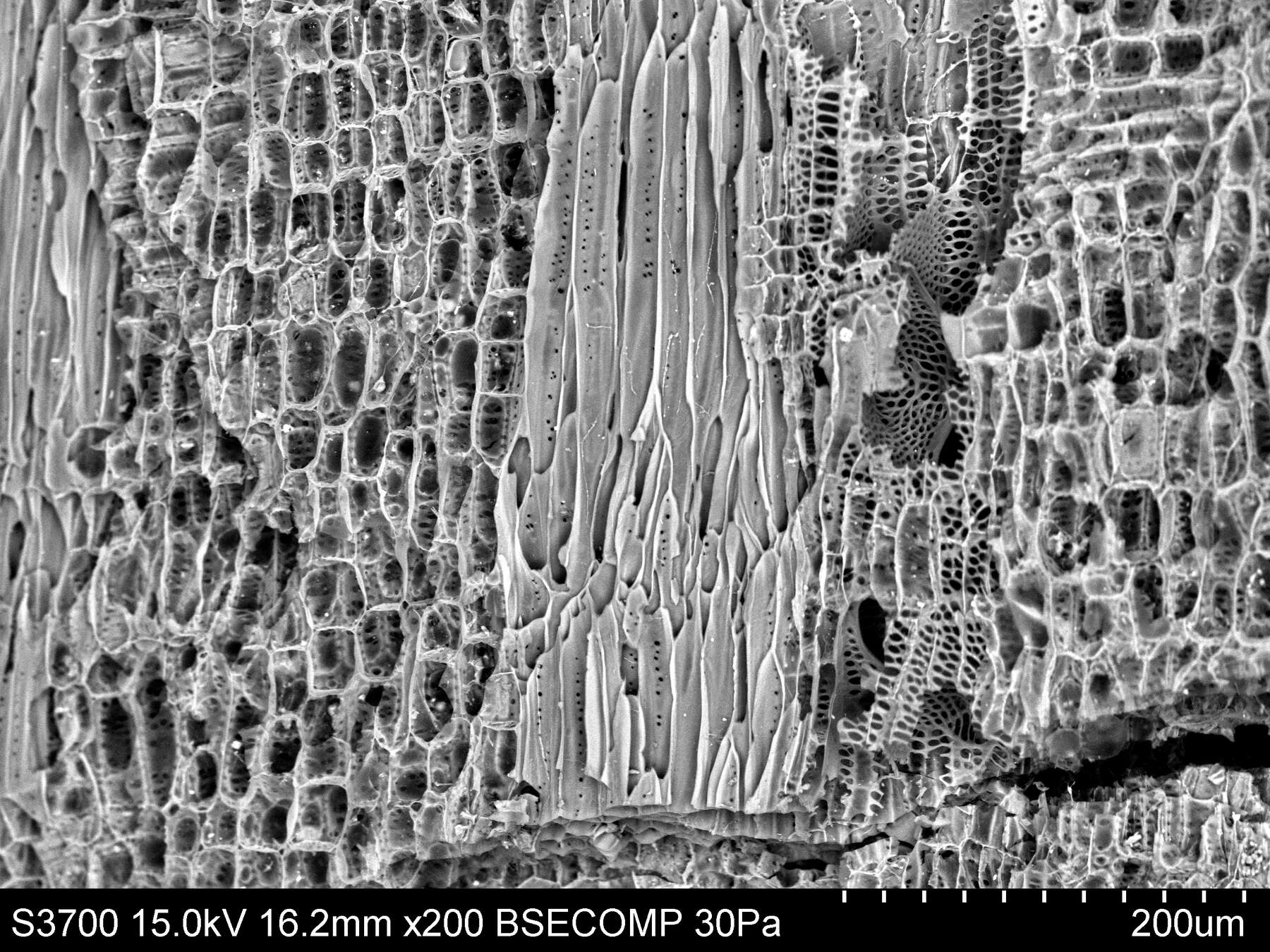

Figure 2.2 Figure 2.3

Figure 2.3 Figure 2.4

Figure 2.4 Figure 2.2

Figure 2.2 Figure 2.3

Figure 2.3 Figure 2.4

Figure 2.4

Why Was Lime Wood So Desirable?

Tilia europaea (including Tilia platyphyllos and Tilia cordata) trees have a long history of wide distribution across Europe and were a ready source of timber over time. Some lime trees can reach heights of 30 meters (100 ft.) and diameters of 1.3 meters (4 ft.). Many have a clear trunk for 15 meters (50 ft.), thus offering good-quality, straight-grown timber for planks, panels, and boards (fig. 2.5). Lime wood planks benefit from being seasoned before use. Controlled seasoning reduces the moisture content in the timber to the required level. As a consequence, strength and elasticity are developed—qualities that maximize the wood’s mechanical and working properties for the carpenter or woodworker. Seasoning lime wood can also minimize its susceptibility to insect attack, permeability, or reduced durability. The color of lime heartwood varies from white or gray to shades of brown, and its sapwood is virtually indistinguishable in color from the heartwood.

Figure 2.5

Figure 2.5 Figure 2.5

Figure 2.5After examining the TS, RLS, and TLS of lime wood in more detail, it is interesting to see how directly the anatomical features contribute to making it such a desirable woodworking resource. Thin sections of Tilia europaea wood (from the reference collections in the wood anatomy laboratories of the Department of Scientific Research at the British Museum) are used here to demonstrate these features (figs. 2.6–2.8).

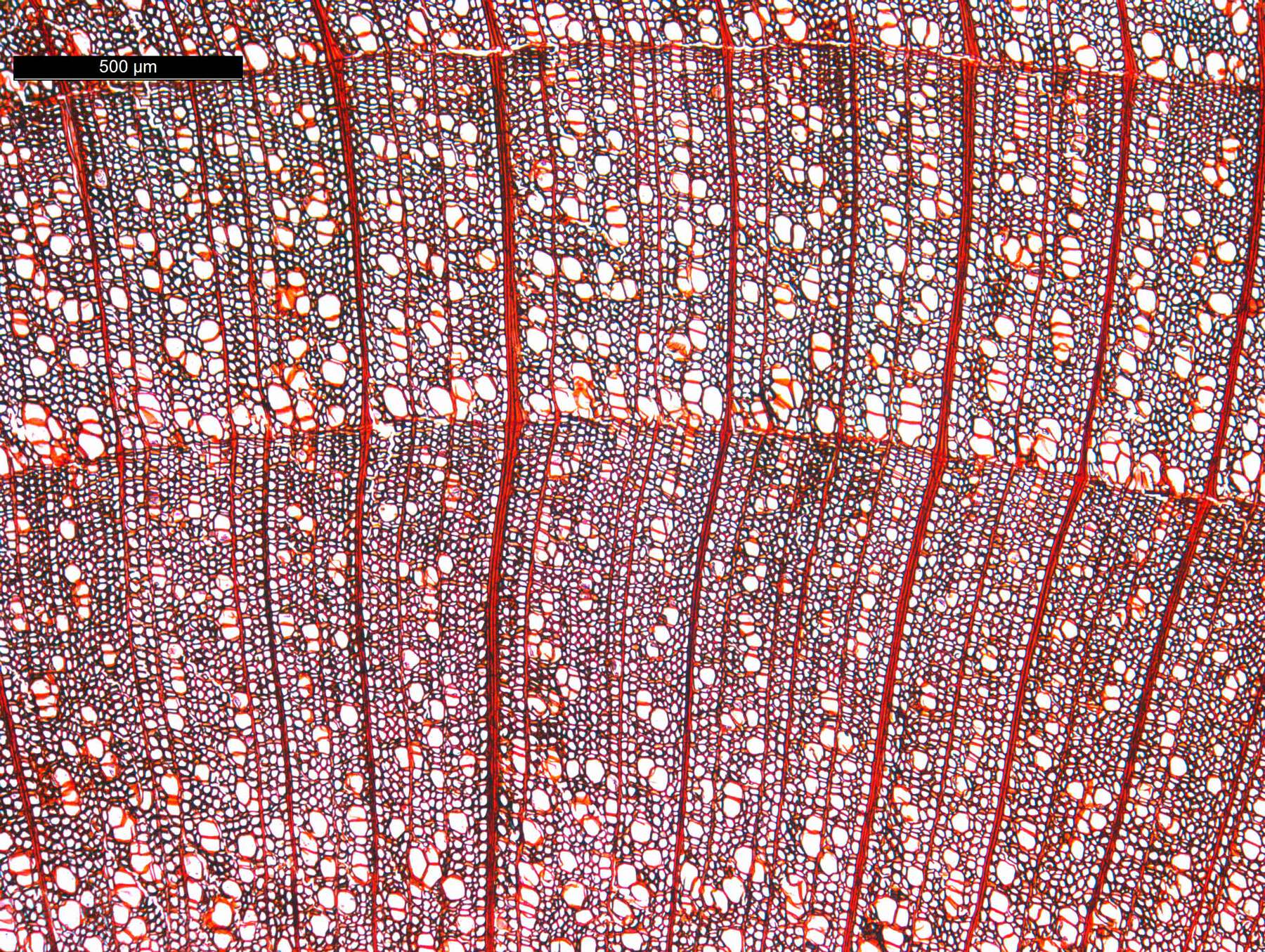

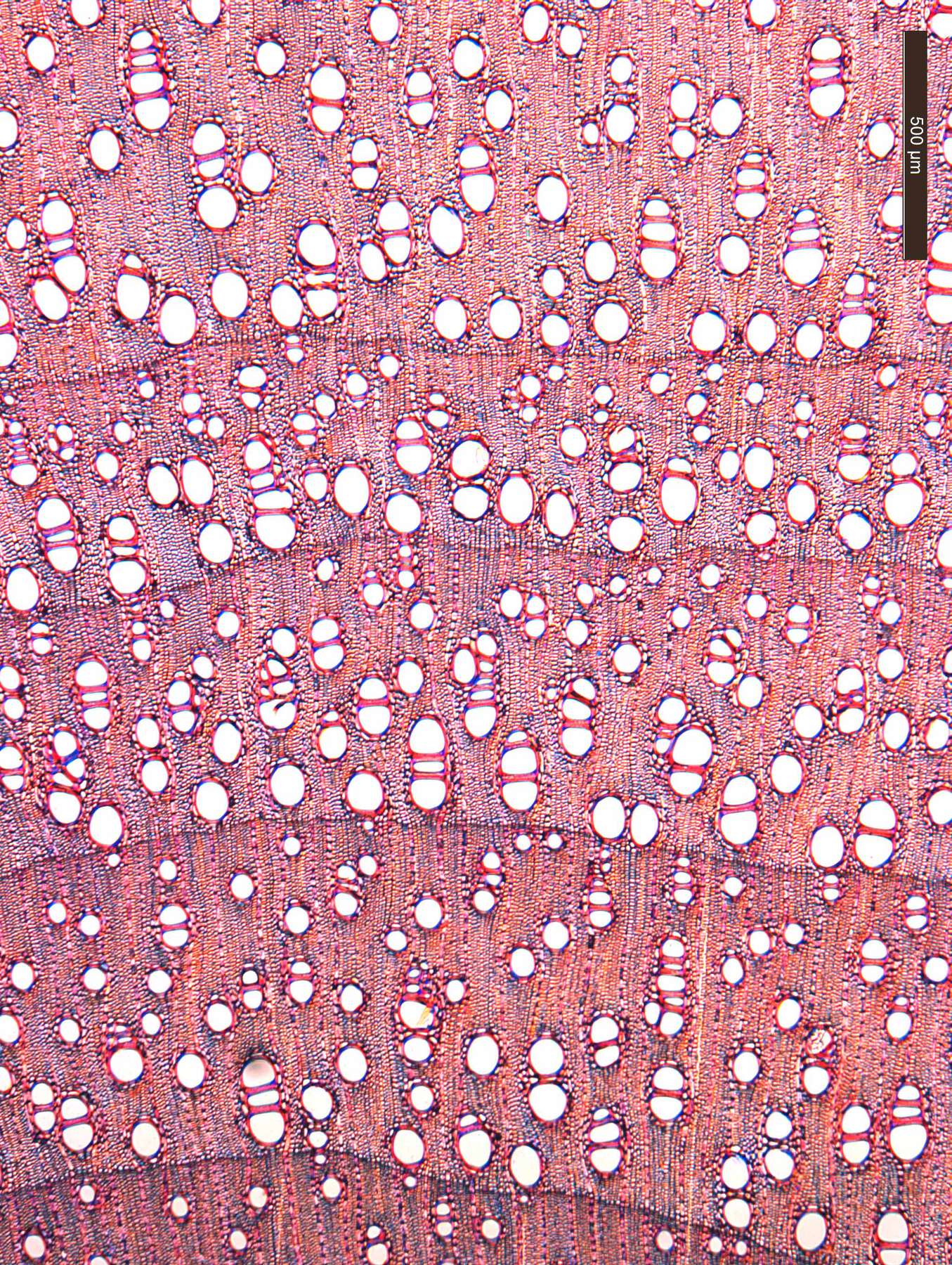

Figure 2.6 shows a transverse thin section of Tilia europaea wood seen in transmitted light in the optical microscope (in this instance, the Leitz Aristomet, modified for biological applications). The growth rings are distinct, and although there is a tendency for a ring-porous distribution of slightly larger vessels at the beginning of the growth ring, most of the vessels are diffuse-porous and have similar diameter size throughout the growth ring. The mean tangential diameter of the vessels varies between 50 to 100 micrometers (microns). Solitary vessels (often angular in outline), clusters, and small vessel chains are present. There are usually between 40 and 100 vessels per square millimeter, sometimes more. Axial parenchyma is present as diffuse-in-aggregates, in narrow bands or lines up to three cells wide, and in marginal or in seemingly marginal bands. There are between 4 and 12 axial rays per millimeter and, although best described from the TLS, narrow rays of 1 to 2 cells wide can be seen in the TS, as can larger rays with widths varying between 4 and 10 cells wide. Some rays show a tendency to flare out at growth ring boundaries.

Figure 2.6

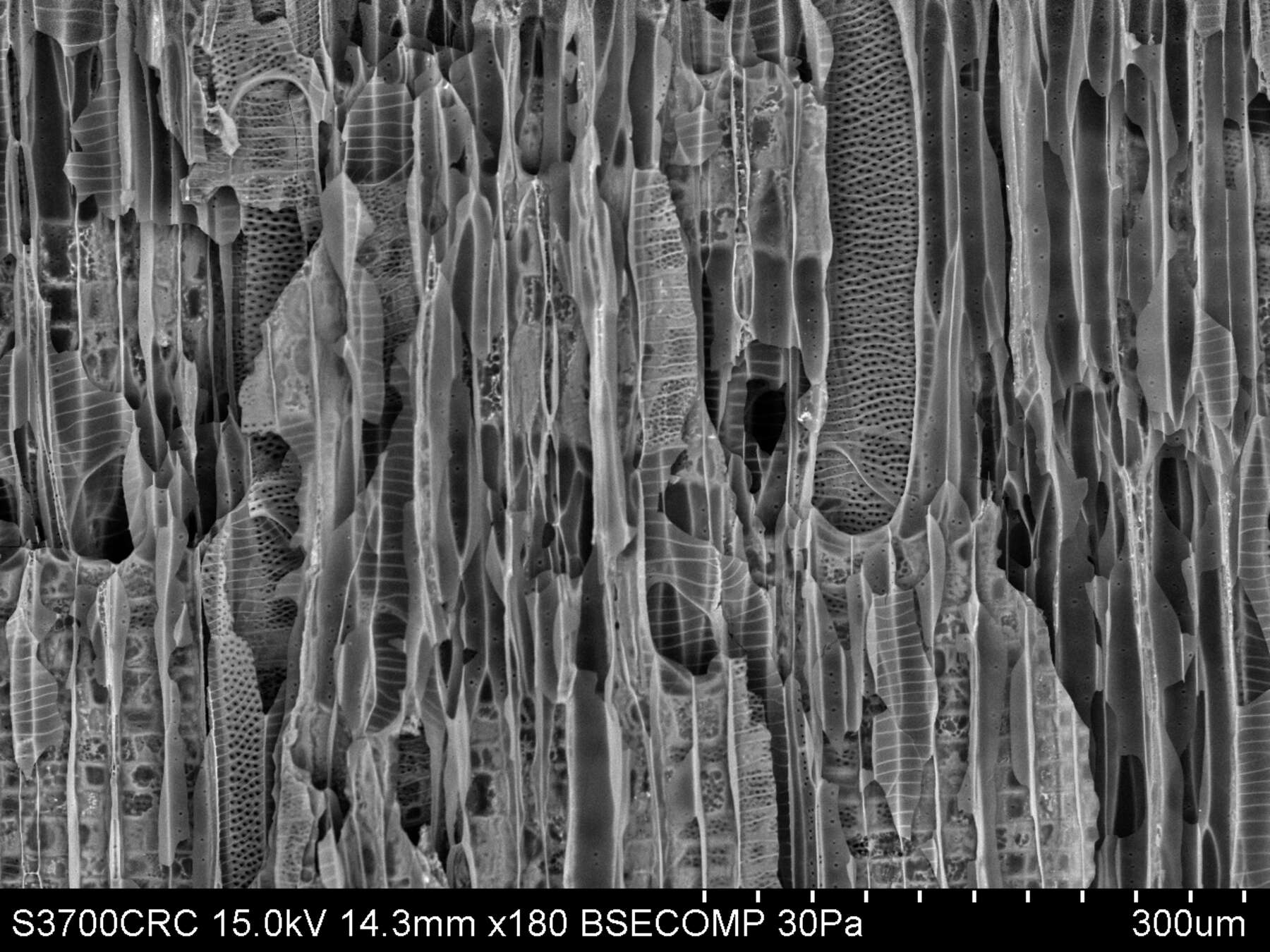

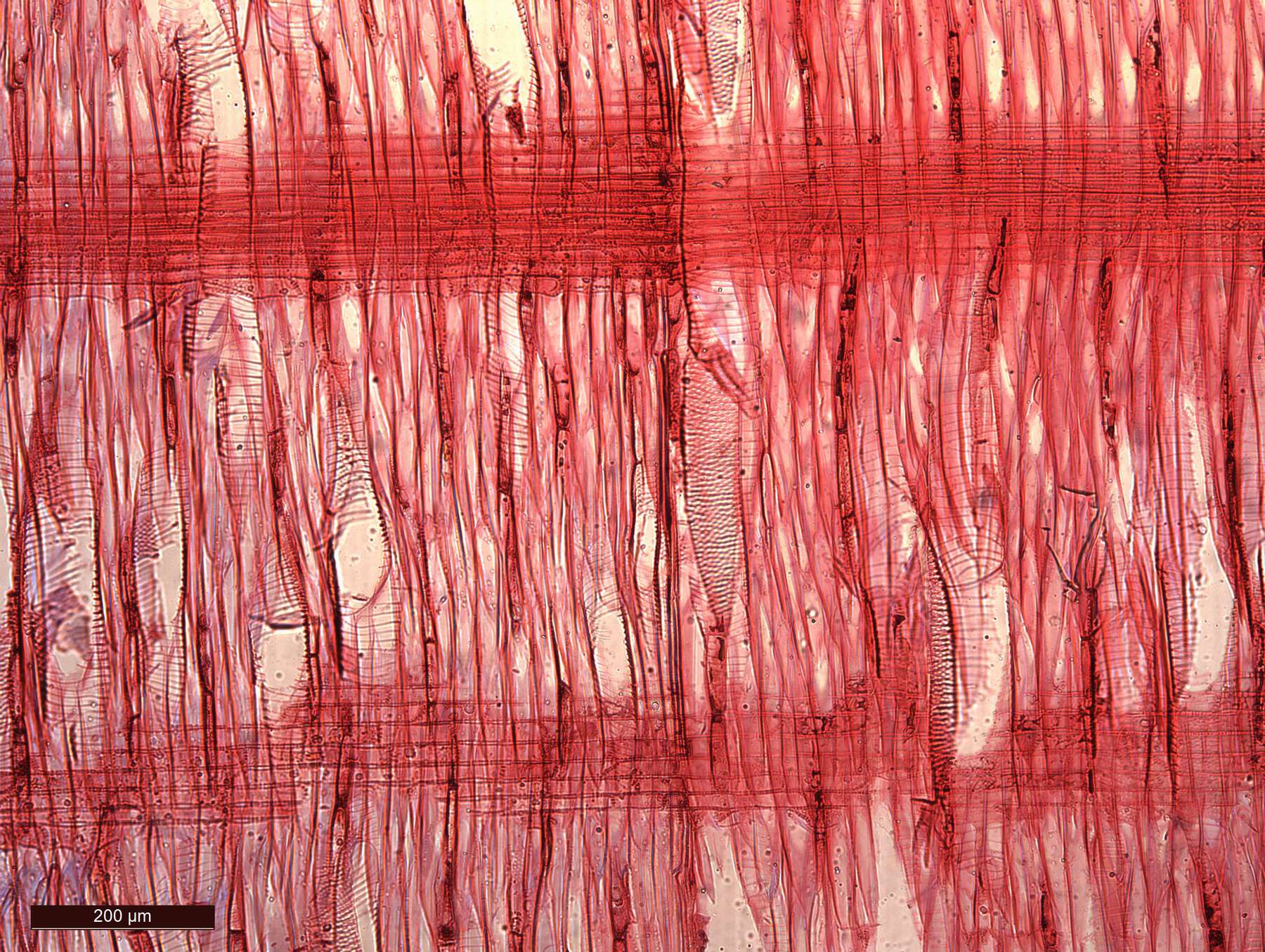

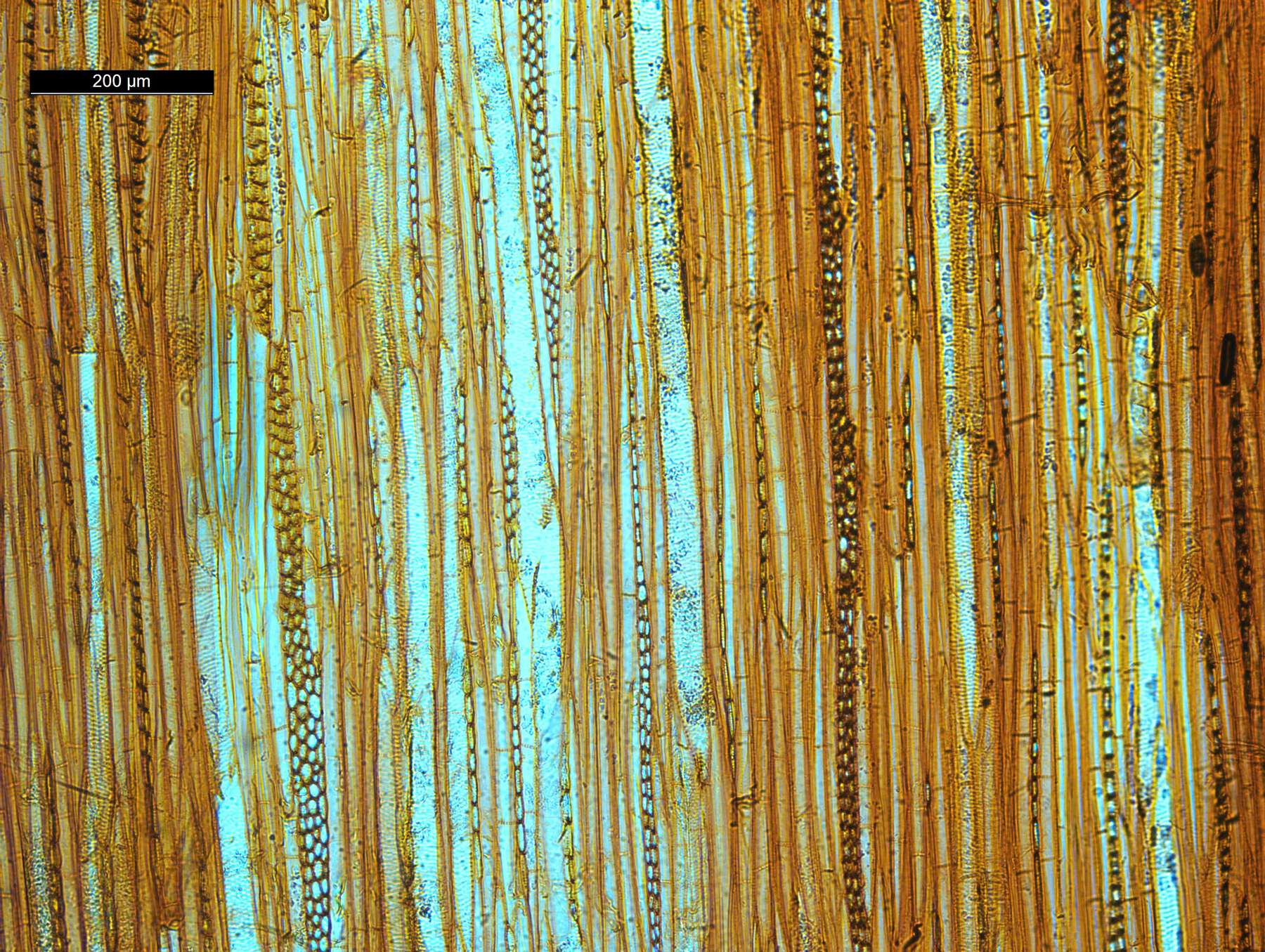

Figure 2.6Figure 2.7 shows a radial longitudinal thin section of Tilia europaea wood seen in transmitted (polarized) light in the optical microscope. The radial longitudinal plane of lime wood was the one most often selected for the prepared surface of the mummy portraits, onto which the and paint layers were applied. By examining the anatomical features, it is possible to appreciate (as it was for those features visible in the TS, as detailed above) why this even-grained wood was so popular. In some rays the ray parenchyma cells are all procumbent, while in others the body ray cells are procumbent with one row of upright and/or square marginal cells. Simple perforation plates with a single circular or elliptical opening are present in the vessels. The mean vessel element length can vary between 350 and 800 microns (µm). Intervessel pits are present in an alternate arrangement. Many of these vessel-to-vessel alternate pits are polygonal in shape and may be small (4–7 µm in diameter) or medium (7–10 µm) in size. Vessel-to-ray pits have distinct borders and are similar to intervessel pits in size and shape throughout the ray cell. Helical (spiral) thickenings—that is, ridges on the inner cell wall—are present in the vessels. The fibers have simple to minutely bordered pits, often found in both radial and tangential walls. These nonseptate fibers may be very thin walled, thin walled, or thick walled. The mean fiber length varies between 900 and 1600 microns.

Figure 2.7

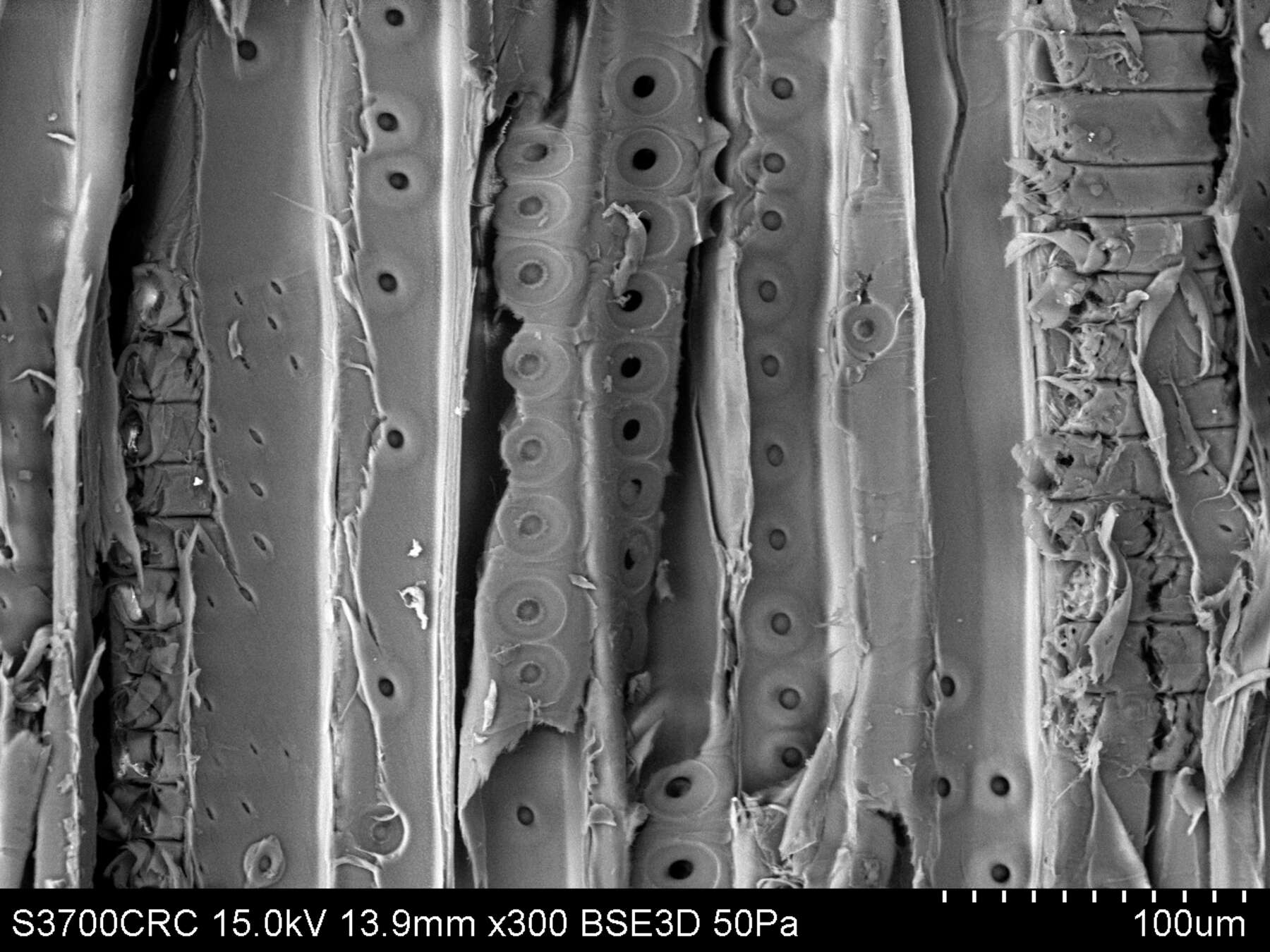

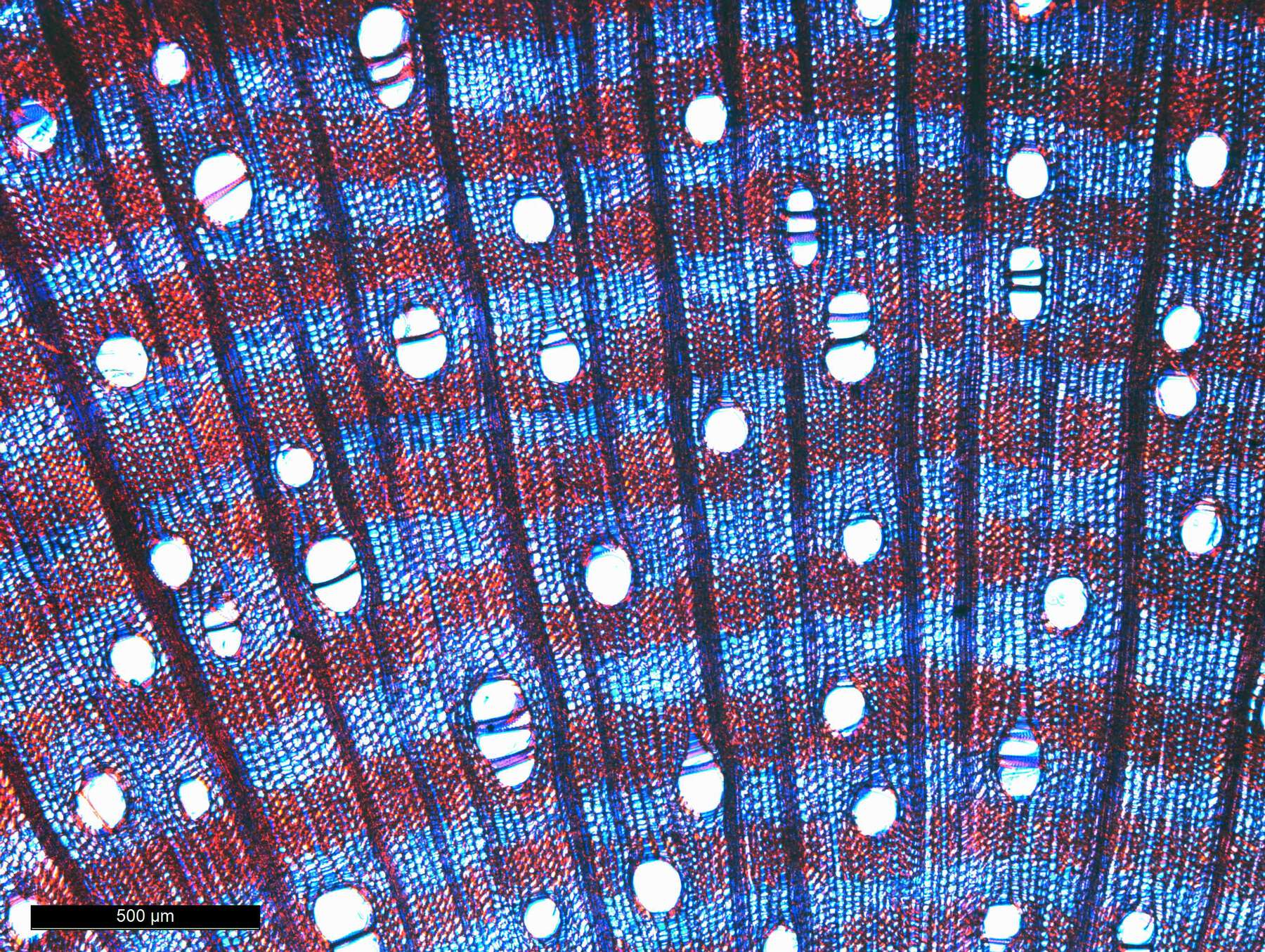

Figure 2.7Some anatomical features are visible in both the RLS and TLS, so for figure 2.8, which shows a tangential longitudinal thin section of Tilia europaea wood seen in transmitted (polarized) light in the optical microscope, the descriptions that follow are of only those characteristics discernible in detail in the TLS. Uniseriate rays (1 cell wide) are common, as are multiseriate rays between 4 and 10 cells wide. Ray height may exceed a millimeter. Some parenchyma strands are composed of 3 to 4 cells; others, 5 to 8 cells.

Figure 2.8

Figure 2.8The combination of these anatomical features is the key to lime wood’s popularity. The even distribution of ray parenchyma cells in their characteristic bricklike arrangement oriented at right angles to the equally evenly distributed vessels, fibers, and axial parenchyma cells results in a highly consistent and uniform cellular structure. These characteristics allow lime wood to perform predictably well when sawn or crosscut, which makes it an ideal timber for those mummy portraits that are fine, thin, light panels, curved to fit snugly in cartonnage wrapping over the face of the mummy.

Other Woods Imported from Europe or Western Asia: Why Choose Them?

Several species of oak are distributed across Europe and into western Asia. Characterized by its strength and sturdiness, oak is often considered to be an all-purpose carving wood, particularly for furniture, doors, and construction. It can be problematic to work on account of the large size of its vessels and the width of its multiseriate rays, which are often more than ten cells wide. Although wide rays may allow for easy radial longitudinal splitting of oak wood, its generally coarse grain means that using oak for mummy portraits required much thicker panels to be cut than those necessary when using lime wood.

Cedar of Lebanon wood had a long tradition of being imported into Pharaonic Egypt for use in high-status coffins and other funerary artifacts. It is often regarded as easy to carve, plane, and polish, although large knots and ingrowing bark can make woodworking difficult, and the wood may be rather brittle. Some cedar wood is renowned for being strongly aromatic and resinous (and therefore insect repellent); these may be useful properties for coffin wood planks but could cause problems for the painted areas of the mummy portrait and other painted panels if the resin seeped through to the surface. It is possible that the continued occasional use of cedar wood, even for portrait panels, reflected in some way its earlier prestige in Egypt. It is believed that cedar of Lebanon wood was traditionally sourced from mountainous forests in Lebanon, but it should be noted that Atlantic cedar, native to the Atlas Mountains in North Africa, is indistinguishable, anatomically speaking, from cedar of Lebanon wood. Closely related to cedars are firs. The most common species of fir tree in Europe is Abies alba, but from an anatomical perspective, the various Abies species cannot be distinguished. Although easy to work, fir tree wood is not durable and has little resistance to insect attack—not a prime choice for portrait panels, therefore.

Yew wood is dense, strong, and heavy but with remarkable flexibility, which makes it a good raw material for archery bows. Most yew wood has many knots and imperfections, so small turned, decorative objects are usually made from it. However, despite a high waste factor during preparation (and consequent higher costs), yew wood, on account of its quality, has been used for cabinetry, furniture veneers, carvings, and musical instruments. The use of yew wood for mummy portrait panels is unusual and may have a particular family or cultural significance.

Native Egyptian Woods: Why Were They Used?

As noted above, by far the most frequently used native Egyptian timber is the local fig wood (Ficus sycomorus), at 15.6 percent of the total number of mummy portraits and painted panels (fig. 2.9). Before discussing fig wood’s properties, the issue of correct botanical taxonomic nomenclature must be addressed. It is important to insist on correct terminology and spelling of Ficus sycomorus, sycomore fig, as attested by international botanical taxonomic authority.5 This type of fig tree, belonging to the Moraceae family, is completely unrelated botanically to the true sycamore tree, Acer pseudoplatanus, which is part of the Sapindaceae family and is mainly distributed across central Europe. It is only correct to write about ancient Egyptian sycamore timber if it has been scientifically identified as Acer pseudoplatanus—the inference being that the wood was imported into Egypt from Europe. It is incorrect to describe indigenous Ficus sycomorus wood as sycamore. Sycamore, spelled with an a, is not a fig tree; it refers to Acer pseudoplatanus, a completely different tree that is not present in Egypt and is anatomically distinct from fig. The spelling is not interchangeable: Ficus sycomorus is spelled with an o, and its common name is sycomore fig (not just “sycomore”).

Figure 2.9

Figure 2.9Fig wood is light, not of high quality, and prone to insect attack. In Pharaonic Egypt thick layers of gesso and covering coffin wood planks minimized these adverse properties to an extent. The popularity of native fig wood in the funerary tradition of Pharaonic Egypt was in part due to the fact that these trees were among the few to attain heights that allowed long coffin planks to be cut. In the Middle Kingdom period particularly, this type of fig tree had considerable religious significance, when it and its fruits (although much smaller than those of the cultivated fig, Ficus carica), were associated with the goddess Nut. Being such an important tree in Egyptian funerary practices of earlier periods, native fig wood’s use for mummy portrait panels could be explained in terms of a fusion of old and new traditions in Roman Egypt. However, like those of imported oak, native fig wood panels would need to be much thicker than those of lime wood, and thus it would be very difficult to make them curve over the mummy head in the same manner as a thin lime wood panel. There may be no single reason for the choice of native fig wood for portrait panels; selection may have been reliant on money and status, or perhaps whether the panel was used as a domestic portrait rather than a funerary one—hence those examples of fig wood portraits in fig wood frames (such as the one from in the British Museum, 1889,1018.1).

The use of the native wood sidr (Ziziphus spina-christi; fig. 2.10) for painted panels is interesting. In Pharaonic Egypt it was unusual to choose woods for the joining elements, which are denser than the planks, and sidr was particularly sought after for creating tight carpentry joins. Sidr, found in tree and shrub forms, inhabits riverbanks, desert wadis, and scrubland thickets. Some of these more marginal habitats may restrict the straight growth of sidr, resulting in twisted or knotty (albeit very dense) timber, with wood suitable for planks or, later, painted flat panels, though the latter are more of a rarity. Figure 2.10

Figure 2.10

Tamarisk (Tamarix aphylla), another native Egyptian timber, is represented in small quantities for painted mummy portraits and panels. Tamarisk wood shows little resistance to attack by fungi and insects, although it is easy to work and would have been readily obtainable from the vegetation of the Nile bank. Its properties include medium bending and compression strength as well as moderate hardness, but its coarse and fibrous texture (fig. 2.11) makes tamarisk a more suitable wood for domestic articles or agricultural tools than for creating mummy portraits or painted panels, which, as with imported oak and native fig, would need to be much thicker than lime wood panels. Figure 2.11

Figure 2.11

Where Are We Now, and What Research Lies Ahead?

In Roman-period Egypt, it is clear that despite maintaining the traditional practice of mummification, there was a fashion for funerary portraiture that echoed Greek and Roman traditions in the Mediterranean region. The excellent condition of preservation of the wood anatomy of these mummy portraits enabled an unexpected revelation from their identifications—the majority of these works are made from European timbers such as lime wood rather than native Egyptian woods. Over the last twenty-one years, the innovative use of high-performance SEM has facilitated the taking of microsamples from mummy portraits and other painted wood panels. The abundance of institutions participating in APPEAR has fostered and supported vital scientific consistency and comparability for the wood identifications. Although more types of woods are being identified as the research progresses, it is remarkable to see that the predominant choice, at around 70 percent, is still Tilia europaea, lime wood, imported from Europe. Currently (as of May 2018), the total of all imported European woods is 79.4 percent, whereas the total for all native Egyptian woods is 20.6 percent. The factors determining individual wood choices constitute intriguing and somewhat elusive elements framing this scientific research, but the search for enlightenment continues.

Interpretation remains the highest priority, preferably in collaboration with APPEAR colleagues. It remains to be seen how far cultural or even regional preferences can be documented, and from what type of evidence. Economic choices need to be evaluated in terms of which wood(s) people could afford to buy or commission. There is a general interest in trying to understand whether workshops, specialist artisans, and carpenters operated alongside or were employed by different stylistic schools of artists and, if so, how, when, and where. Of particular interest are the panels on lime wood and whether they were imported into Egypt as raw timber or prepared panels, or even whether some of the lime wood mummy portraits could have been entirely crafted in Europe.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all those in the APPEAR project who are actively supporting this research, including those institutions that have permitted microsampling of their mummy portraits and nonportrait painted panels. Thanks are due to British Museum colleagues who collaborated in the pre-APPEAR phases of the mummy portrait wood identification project.

Notes

- See ; ; ; ; ; ; . ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- See the International Plant Names Index (IPNI) at http://ipni.org and specifically Ficus sycomorus L. at http://ipni.org/n/853797-1. ↩