3. The Matter of Madder in the Ancient World

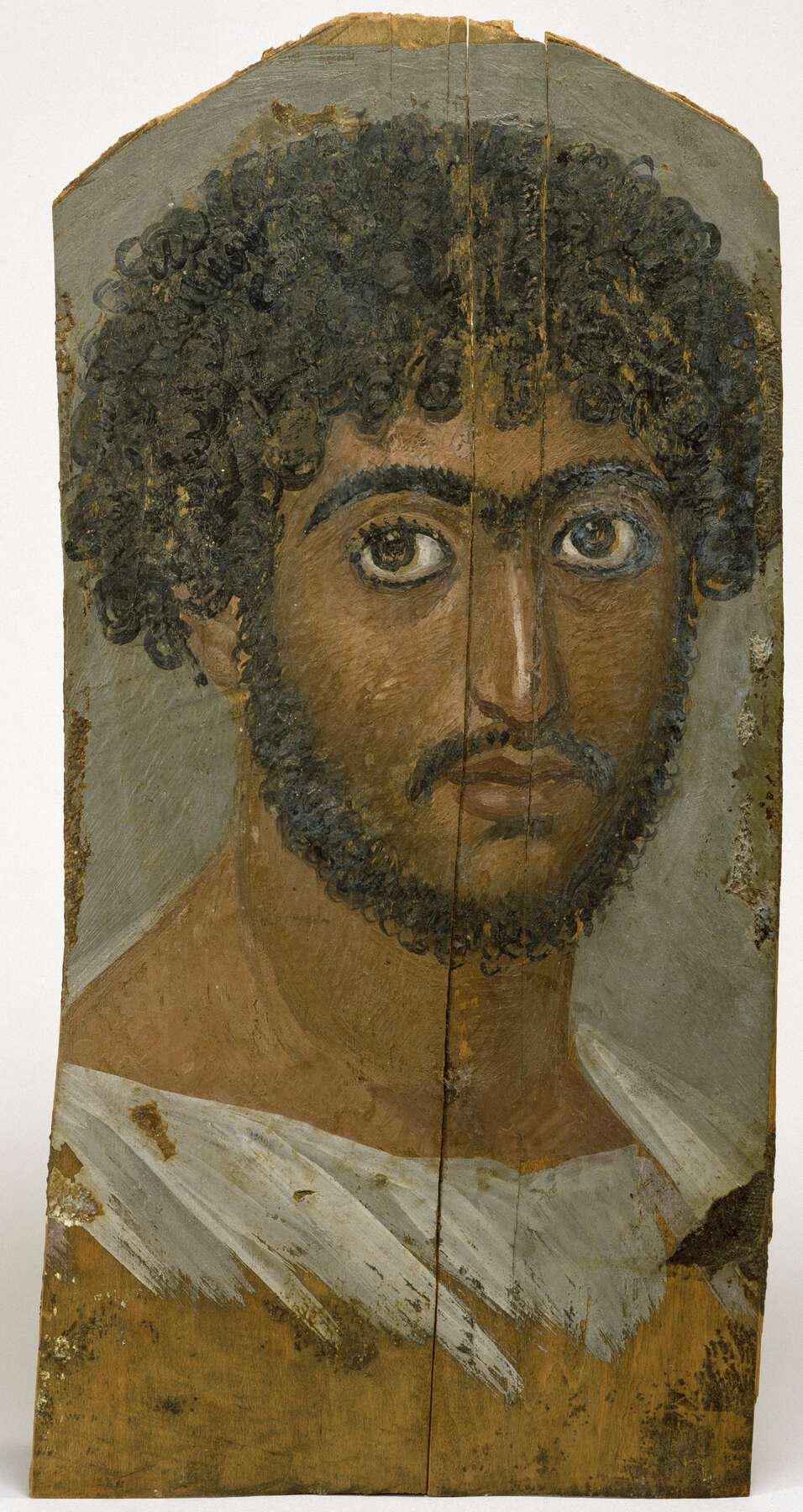

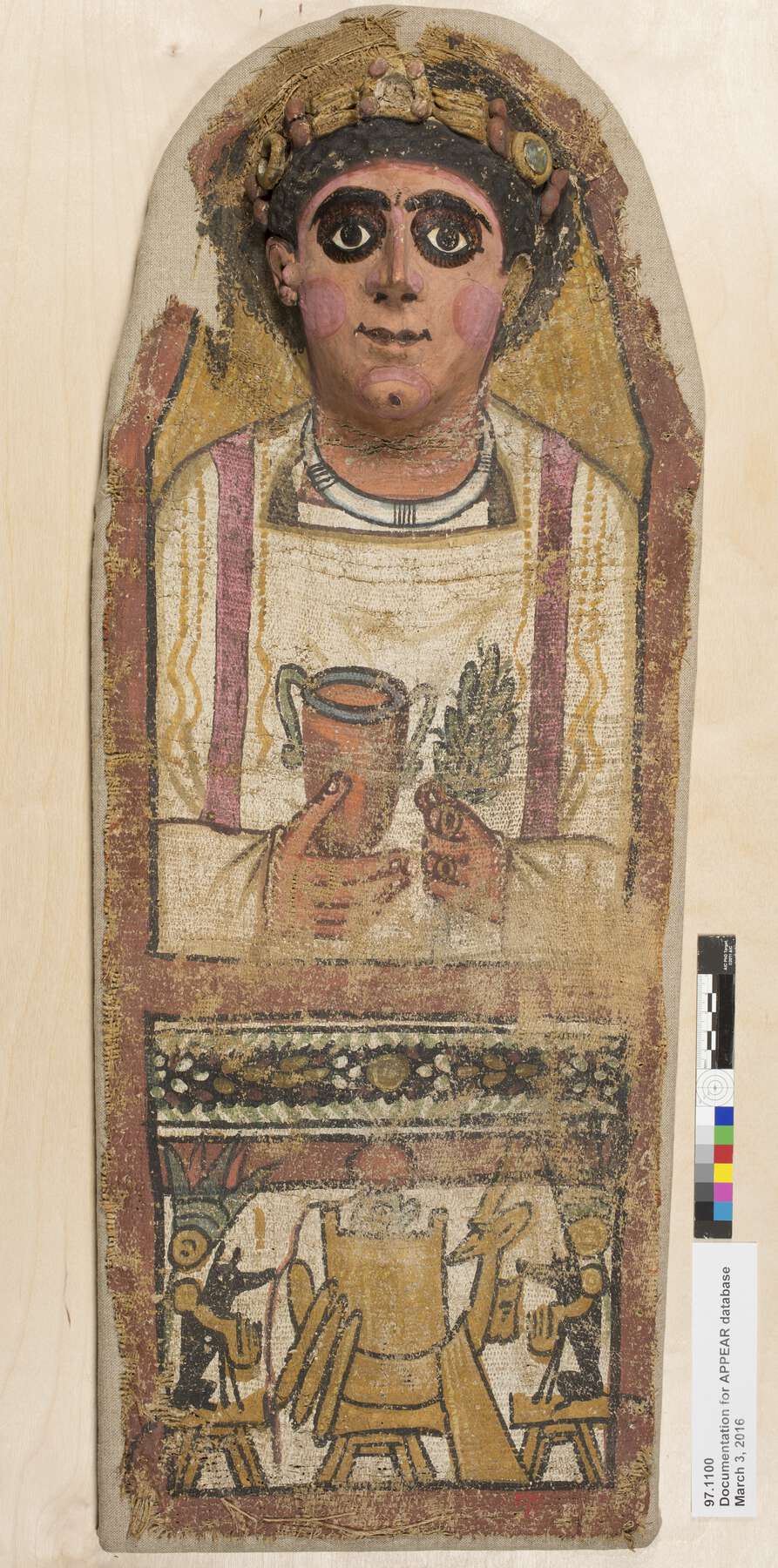

, a , may be one of the more common colorants used in Egyptian mummy portraits. As a pure pigment, it is pink or red, sometimes slightly purplish, and is most often noted as the major coloring in red and purple drapery and (figs. 3.1 and 3.2). Madder has been found mixed with a blue pigment in purple drapery, and it is commonly noted on lips and highlights on faces. Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1 Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2

This paper will briefly review the nature of madder as well as methods by which it can be identified by noninvasive procedures and analyses of samples; a few specific instances of its use in mummy portraits will be described. Madder has been the subject of extensive research, from many points of view, and only a very few selected publications from this rich literature can be cited here.

The Rubiaceae family of plants, comprising more than thirteen thousand species in 617 genera,1 includes many from which red colorants can be extracted. Colorants from Rubiaceae have been utilized in many parts of the world as textile dyes and pigments. In Europe and western Asia, perhaps a half dozen Galium species were likely to have been used as textile dyes.2 In Europe, the dyes from this genus are commonly known as bedstraws and woodruffs; a related dye, Asperula tinctoria L. (often called dyer’s woodruff), was also probably important. Although several Rubia species are found in many of the same regions as Galium, their range does not extend as far north as that of Galium, and they grow in regions farther south. Rubia tinctorum (often referred to as common madder or dyer’s madder) is found in central and southern Europe, northern Africa, and central Asia. Rubia peregrina (wild madder) has a range mostly restricted to central Europe. Rubia cordifolia (Indian madder or munjeet) is found in central and eastern Asia, eastern Africa, and parts of Australia. Pliny the Elder suggested that by the first century AD at least, R. tinctorum was widely grown throughout Italy and the eastern Mediterranean, and it was a ubiquitous source of red dyes for textiles.3 There is less certainty about the relative availability of the other madders.

The word madder is usually restricted to species in the Rubia genus. Because many of the same chemical compounds occur in Rubia, Galium, and Asperula, for the purposes of this paper madder will refer to red colorants extracted from any of these botanical sources.

The colorants are found in the cores of roots and rhizomes (underground stems). At certain times of the growing season, the roots exhibit a pink to strong red color, and it is easy to understand how they would have been attractive as potential color sources (figs. 3.3 and 3.4). Extracting the colorants is simple: dried roots are crushed and soaked in hot water. Simple water extracts, if used alone, would not have been fast to moisture if used as stains or dyes, and it seems likely that early in the historical use of madders as colorants, they were combined with inorganic mordants to attach them to textiles’ fibers.4 Inorganic ions, such as aluminum, form complexes with natural compounds found in the roots that facilitate strong bonds to textile fibers and also typically turn the roots’ colors more reddish shades. For use as pigments, the extracts were probably prepared as lakes, as discussed below.

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3 Figure 3.4

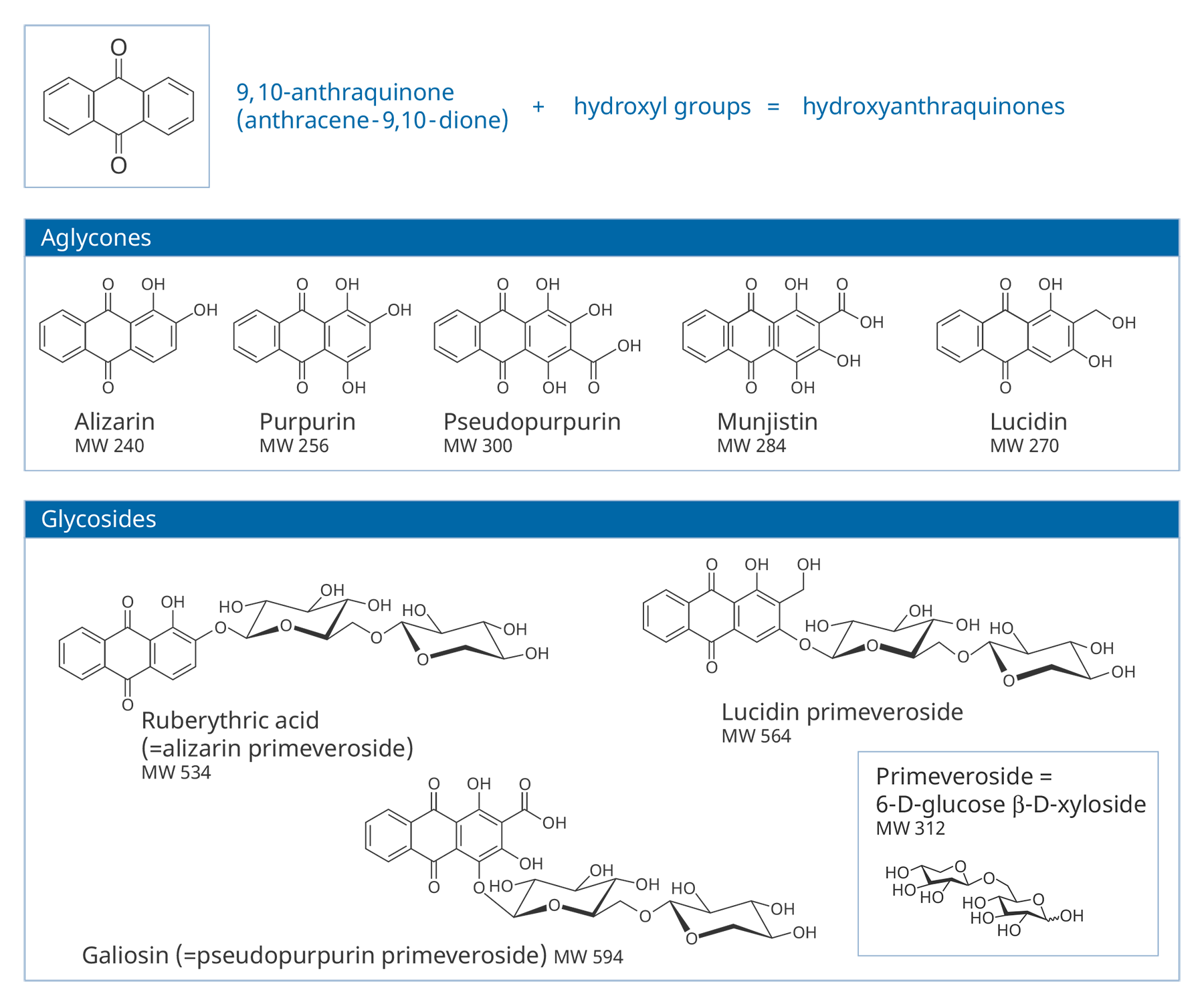

Figure 3.4The compounds responsible for the color are hydroxyanthraquinones (HAs). HAs found in Rubiaceae are derivatives of 9,10-anthraquinone, with hydroxyl (and sometimes other groups) substituted on ring A. In roots, many of these are present mostly in the form of glycosides, in which a HA (or aglycone) is bonded to a sugar molecule (a monosaccharide or disaccharide). Some common glycosides are primeverosides, in which the HA is bonded to the disaccharide primeverose. About three dozen different HAs have been identified in the roots of Rubia tinctorum, the most extensively studied of the madder-producing plants.5 Structures of some common aglycones and glycosides in madders are shown in figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5

Figure 3.5Air-drying of fresh roots leads to hydrolysis of the native glycosides by endogenous enzymes, although glycosides may be preserved if fresh roots are strongly heated, which destroys the enzymes.6 Glycosides can also be easily broken down during other steps by which plant extracts are prepared and attached as dyes to fibers or prepared for use as pigments. As a result, samples of pigments or dyes extracted from textiles usually contain only aglycones. There can be considerable variations in the specific aglycones and their relative amounts found in the end products of their use—be it textile or pigments—even if they were prepared from only one species of plant.7

HAs can also be extracted from a number of types of scale insects, and at least four major types have or may have served as important historical sources of dyes in the ancient world: (from Kermes vermilio), Armenian cochineal (Porphyrophora hamelii), Polish cochineal (Porphyrophora polonica), and lac (Kerria lacca).8 The HAs in these sources, which contain substituents on rings A and C, do not overlap with any found in Rubiaceae.

Identification of specific HAs has been carried out by several techniques. Of them, the one that in principal requires the smallest sample is surface-enhanced (SERS). It has been shown that three of the major HAs found in many Rubiaceae (alizarin, purpurin, and pseudopurpurin) can be identified by SERS; however, if more than one HA is present in a given sample, SERS may detect only one of them.9

Typically, techniques that can confidently identify two or more HAs simultaneously require larger samples than does SERS. (The actual sample size or weight required for any analytical technique depends on many factors, including the concentration of the compounds of interest in the sample.) Liquid chromatography (LC) is a proven workhorse, either with diode array detectors (LC/DAD), mass spectrometer detectors (LC/MS), or both (). Successful applications of LC to Rubiaceae-based dyes and pigments are extensive.10 Other mass spectrometric techniques, not combined with chromatography, have been less commonly utilized to date.11 Noninvasive methods by which the presence of madder can be established or at least hypothesized are discussed later.

Alizarin, purpurin, and/or pseudopurpurin are the HAs most commonly detected in chromatographic analyses of madder pigments. Many researchers have used the types and relative amounts of these HAs, as indicated by peak heights or areas in chromatograms, to hypothesize the botanical source of madder in specific samples.12 Of the various genera and species noted earlier, alizarin is the predominant HA only in certain extracts from R. tinctorum. If alizarin is absent or negligible, then Galium, R. cordifolia, or R. peregrina are the more likely sources. Conclusions can be problematic, as profiles of HAs are profoundly affected by processing of the raw materials, procedures used to prepare a dye or lake, and preparation of samples for analysis. In some instances, certain other HAs, present in minor amounts, may suggest specific botanical sources, but there is no general agreement on how useful the presence or absence of such minor components is for this purpose.13

The earliest published occurrence of a madder dye in a cultural artifact is in some (now unavailable or lost) fragments from Mohenjo-daro, an Indus valley site dated to about 3000 BC.14 However, the analysis may not have been correct given techniques available at that time. The earliest confirmed identification of madder (from an analysis carried out by SERS) is on an Egyptian leather quiver fragment dated to the Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11 (ca. 2124–1981 BC), excavated at Thebes.15 The dye was rich in purpurin.

Some textiles excavated at a late second millennium BC site in the Tarim basin of western China were likely dyed with R. tinctorum.16 This species has also been identified as the source of red dye for some textiles, dated to the eleventh and tenth centuries BC, excavated at Timna, Israel.17

Analyses of textiles, apparently discarded between the first and third centuries by Roman garrisons at eastern desert sites in Egypt, identified two “types” of madder,18 likely from more than one type of plant. Dyers must have been aware of how different plants and manipulations in extraction and preparation procedures could affect the tint of the final product.

Textile dyeing and the making of lake pigments were separate operations, but lakes may have been made in some of the same workshops in which dyed textiles were produced. In later European history, the colorants used to make lakes were at least at times extracted from scraps of dyed textiles, and lakes in the ancient world could also have been made from such scraps.19

The earliest examples in a recent compendium of madder-based pigments in the ancient world are from Cypriot pottery of the eighth and seventh centuries BC; these works reportedly contained alizarin, purpurin, and possibly pseudopurpurin.20 Some paint samples contained significant alizarin, while others contained little or no alizarin. A small bowl of pseudopurpurin-rich madder lake was among several that were excavated at , the region in which many mummy portraits are thought to have been created.21

Analysis by LC/MS of purple pigments from a Hellenistic sculpture identified an alizarin-poor madder mixed with , but traces of insect dyes were also found: a type of cochineal and lac.22 Lakes made exclusively from insect dyes may have been utilized in the ancient world, but there are few examples as yet.

Little is known about how lake pigments were made in the ancient world. Typical later procedures in Europe involved mixing the root extracts with a soluble aluminum sulfate salt (such as alum), then adding an alkali (such as plant ash) to precipitate the lake. The alkali can be used first, followed by addition of the soluble aluminum salt.23 Particles of lakes created by these procedures consist of HAs in complexes with aluminum (possibly also with smaller amounts of other elements, such as calcium) within particles of aluminum sulfate and mostly amorphous aluminum hydroxide.24 , if used as an alkali, can result in a lake that contains calcium sulfate, which would be precipitated during the manufacturing process. After drying, a lake pigment can be ground like a mineral pigment, then mixed with the paint medium.

The substrates of ancient madder-type lakes have been identified as aluminum rich, clay containing, or based on calcium carbonate or calcium sulfate.25 The possible presence of extenders (or white pigments) in samples makes precise identification of the lake substrate difficult, since most published analyses have not been carried out on isolated lake particles.

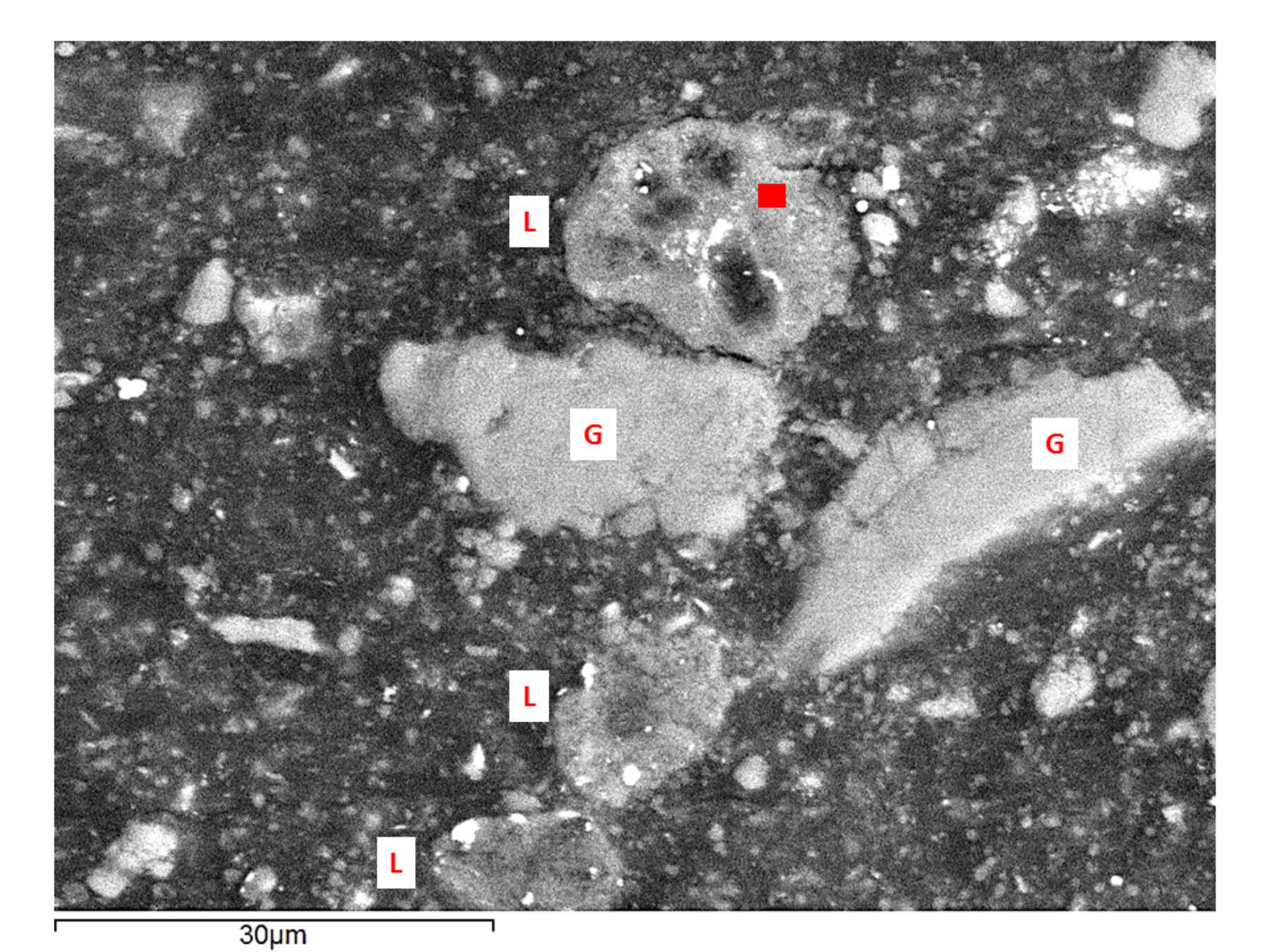

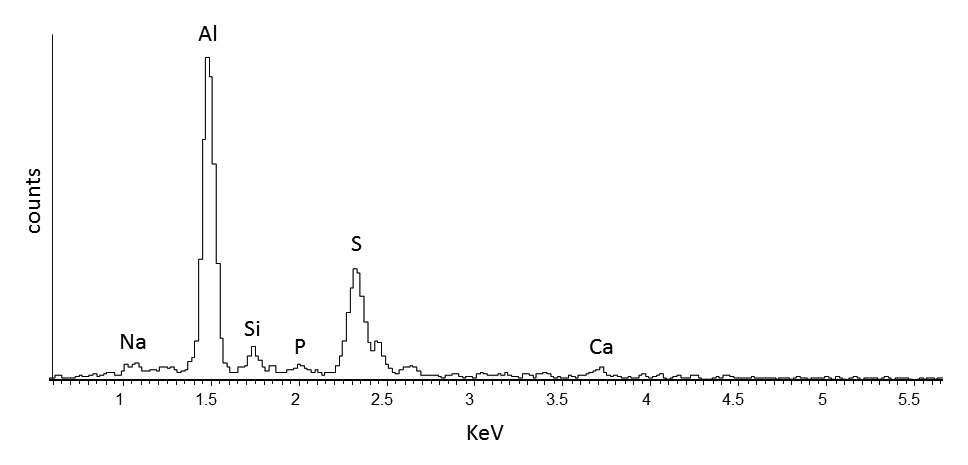

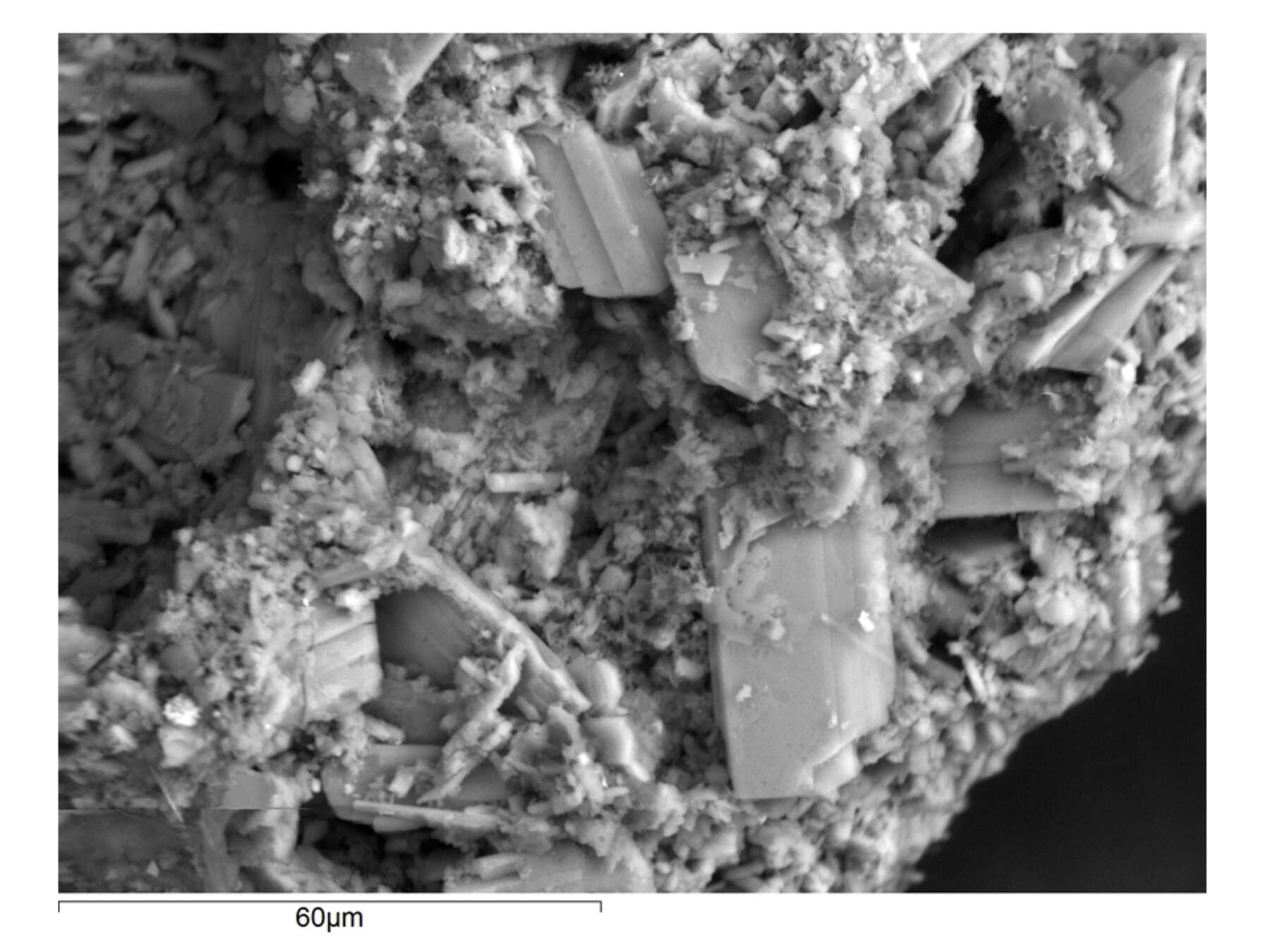

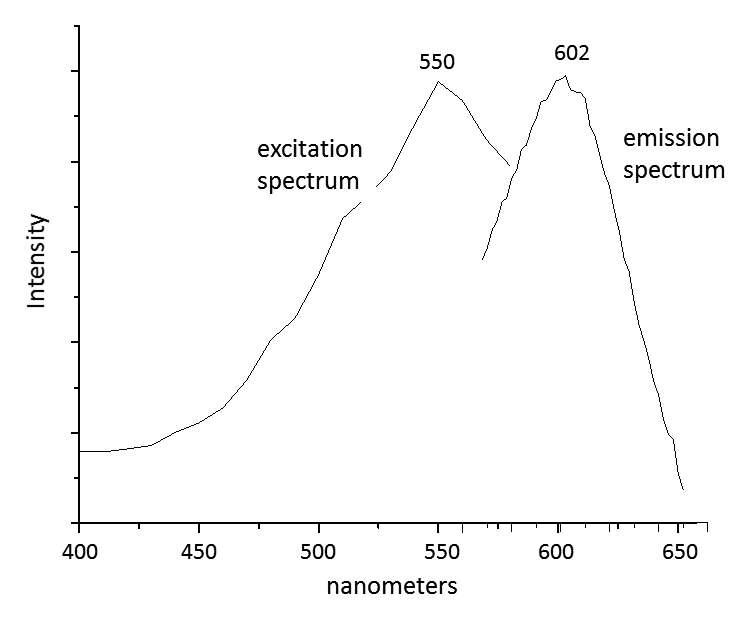

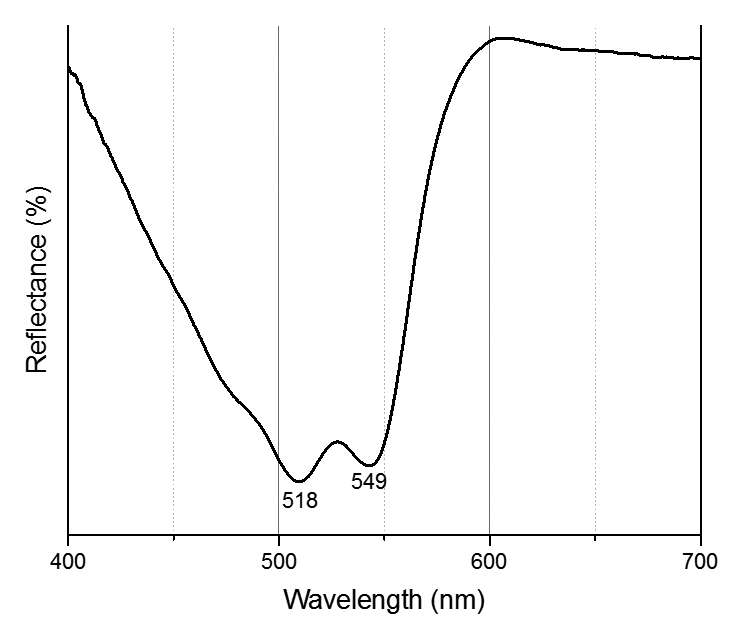

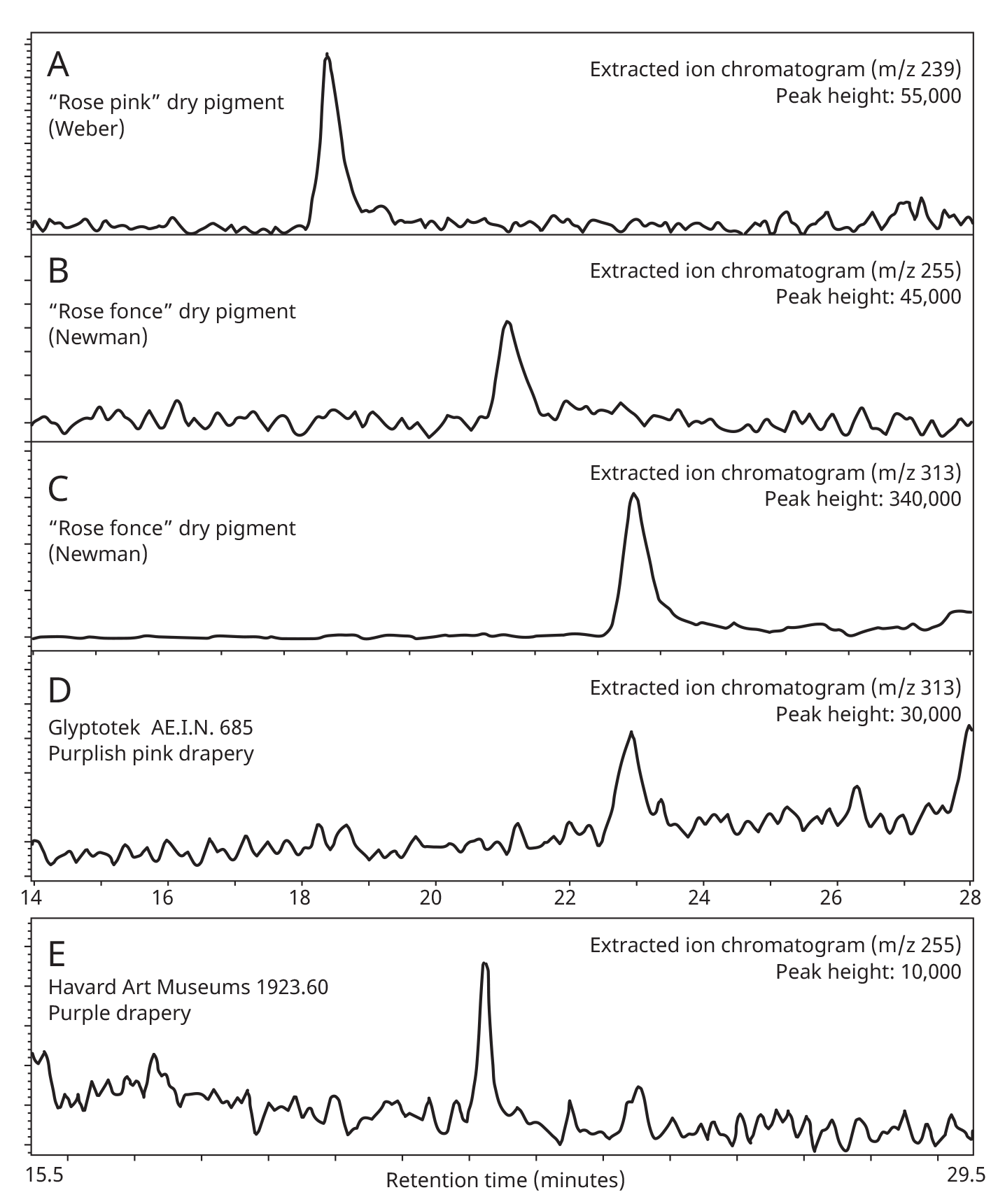

When paint cross sections containing lake particles are available, the substrates of the lake can be studied by scanning electron microscopy / energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (SEM/EDS) with little interference from other compounds present in the paint sample. Figure 3.6 is an image of a cross section from a purple clavus in a mummy portrait (see fig. 3.1). The purple paint contains , natrojarosite, , and a red lake that fluoresces orange. The SEM/EDS spectrum from the largest lake particle in the image (fig. 3.7) is quite similar to spectra from madder lakes in later European paintings: aluminum is the major element, with some sulfur and smaller amounts of several other elements associated with the raw materials that had been used to make the lake. The particle encompasses several very small grains of , perhaps an unintentional component of the lake. Lake-containing samples from mummy portraits examined at the Museum of Fine Arts often contain angular particles of calcium sulfate (usually gypsum) and finer-grained material that is rich in aluminum. The latter regions exhibit orange fluorescence. A chip of one pink paint sample is shown in figure 3.8. In this instance, the gypsum was likely added to the paints as a ground mineral after the lake was manufactured, rather than precipitating during manufacture. A high-resolution transmission electron microscope study of a single, fairly large purplish pink lake particle from a purple clavus in a mummy portrait (see fig. 3.2) suggested that the lake particle, as in the other examples just mentioned, mainly consisted of aluminum compounds.26 But lead-rich particles were detected—perhaps unintentional residues from a pot used in the manufacturing process. In a mummy portrait from Tebtunis, lead white was found to be the predominant white pigment.27 Drapery and clavi that contained substantial red lake were found to contain significant amounts of calcium sulfate and little or no lead white. It was speculated, quite reasonably, that calcium sulfate may have served as the lake substrate. As mentioned above, calcium sulfate could also have been added as a ground mineral to madder lake prepared on an aluminum-rich substrate, to adjust depth of color. The ability to identify pigments without the need to take samples is important in all cultural heritage research. Some madder-based lakes strongly fluoresce orange or orange-pink under ultraviolet radiation (), which has long been utilized by conservators to tentatively identify such lakes on painted objects.28 The pink or purple clavi and fabrics of mummy portraits and facial features (such as lips and cheeks) often exhibit such strong fluorescence, suggesting that madder was commonly used in these areas (figs. 3.9 and 3.10). Noninvasive instrumental analysis techniques that support identifications of madder include fluorescence spectroscopy and reflectance spectroscopy. The former can, in some instrumental setups, record excitation and emission spectra, permitting the excitation and the emission wavelength maxima to be determined—two fundamental properties of fluorescent compounds. Typical for madder lakes that have been studied to date are excitation maxima around 550 nanometers and emission maxima around 600 nanometers (fig. 3.11), but these wavelengths can vary by 10 or more nanometers, depending on plant source, preparation procedures, and other factors. Purpurin fluoresces considerably stronger than does alizarin,29 and the most strongly fluorescing madders are probably those richest in purpurin (or pseudopurpurin, which has a fluorescence probably similar to that of purpurin).30 Some current imaging techniques utilize light sources in the visible range, which are closer to the excitation maximum for the pigment than ultraviolet radiation, as well as filters on digital cameras that restrict the range of captured fluorescence emission.31 Another fundamental property of fluorescent compounds is fluorescence lifetime (usually no more than a few nanoseconds), which has been applied noninvasively to a mummy portrait.32 can distinguish between plant- and insect-derived HAs.33 A spectrum typical for madder is shown in figure 3.12, from the clavus in the mummy in figure 3.9. The valleys in spectra are usually (but not always) shifted to higher wavelengths for insect reds. The exact positions of the valleys can vary, depending on how a given lake was prepared. Relatively few identifications of the specific HAs in red lakes from mummy portraits have been published to date.35 Thus far, madders appear to be purpurin or pseudopurpurin rich. A few analyses carried out by LC/MS for this paper are briefly discussed below. The analyses were performed on a capillary LC with an attached ion trap mass spectrometer, using a column and gradient elution program that is fairly standard for studies of dyes in cultural artifacts.36 Using the most common form of ionization (electrospray ionization, or ESI), the most abundant ion detected by the mass spectrometer for a given compound is usually the pseudomolecular ion. In negative polarity, this ion has a mass of 1 dalton less than that of the molecule being analyzed; in positive polarity, the ion has a mass of 1 dalton more. In order to analyze dye-containing pigments, which are most often in the form of lakes, the lake first must be hydrolyzed, putting the dye molecules into solution. Analyses reported here use a sample preparation procedure (dissolution in boron trifluoride in methanol) first described in 1996.37 Lakes are easily broken down, but acidic compounds are at least partially methylated, the result being that acidic compounds (such as pseudopurpurin and munjistin) may exhibit two peaks: one for the aglycone and one for the methylated aglycone. Extracted ion chromatograms are the most sensitive means of detecting compounds present at very low levels when a mass spectrometer is used as a detector. The signal for the most abundant ion for a given compound (usually the pseudomolecular ion) is selected for display. If such an ion occurs at the expected retention time for a specific compound, that compound can be concluded to be present. For the new analyses discussed here, it is required that a visible peak be apparent in the extracted ion chromatogram at the appropriate retention time. Extracted ion chromatograms for twenty-nine different compounds treated with the boron trifluoride reagent, including all common major and minor HAs in plant and insect sources, are examined. The reference materials were analyzed by the same procedures as the mummy portrait samples. Results for two intentionally small samples (approx. 10 µg) of commercial madder lake pigments on aluminum-containing substrates are shown in figure 3.13. The solutions that were injected into the LC were diluted until nearly colorless, so that the concentrations of colorants would be similar to those encountered in actual samples taken from paintings. With the instrumentation employed, these samples showed no discernable peaks from either the diode array detector or the general displays of the mass spectrometer data (total ion chromatograms and base peak chromatograms). These analyses of very small reference samples reasonably reflect what can be expected from very small paint samples. Details of extracted ion chromatograms from LC/MS analyses of reference pigments and samples from mummy portraits. All analyses carried out using electrospray ionization (ESI) in negative polarity. (A) “Rose pink” dry pigment, manufactured by Weber; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Forbes Collection 16 (B) and (C) “Rose foncé” dry pigment, manufactured by Newman, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Forbes Collection 15 (D) Purplish pink paint from drapery in Mummy Portrait, Romano-Egyptian, AD 100–200, media not identified, 50.2 x 22.4 cm (19 ¾ x 8 13/16 in.), Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, ÆIN 685 (E) Purple paint from drapery on portrait in fig. 3.1 Samples prepared by reacting with approximately 5 percent boron trifluoride in methanol. Vertical scales adjusted individually; actual peak heights are indicated. Compounds plotted: alizarin (m/z 239), purpurin (m/z 255), methyl ester of pseudopurpurin (m/z 313). Instrumental conditions were different for (E), which resulted in shifted retention times. Details of extracted ion chromatograms from LC/MS analyses of reference pigments and samples from mummy portraits. All analyses carried out using electrospray ionization (ESI) in negative polarity. (A) “Rose pink” dry pigment, manufactured by Weber; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Forbes Collection 16 (B) and (C) “Rose foncé” dry pigment, manufactured by Newman, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Forbes Collection 15 (D) Purplish pink paint from drapery in Mummy Portrait, Romano-Egyptian, AD 100–200, media not identified, 50.2 x 22.4 cm (19 ¾ x 8 13/16 in.), Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, ÆIN 685 (E) Purple paint from drapery on portrait in fig. 3.1 Samples prepared by reacting with approximately 5 percent boron trifluoride in methanol. Vertical scales adjusted individually; actual peak heights are indicated. Compounds plotted: alizarin (m/z 239), purpurin (m/z 255), methyl ester of pseudopurpurin (m/z 313). Instrumental conditions were different for (E), which resulted in shifted retention times. Results for samples from two mummy portraits are included in figure 3.13. Purplish pink drapery in one was found by other analysis (SEM/EDS, , and Raman microscopy) to contain a large amount of gypsum, relatively small amounts of red iron oxide, yellowish-brown natrojarosite, and probably some lead white, as well as an orange-fluorescing red lake on an aluminum-rich substrate; only pseudopurpurin was detected by LC/MS. Purple paint from a second painting (see fig. 3.1; see cross section in fig. 3.6) was found to contain contain gypsum, natrojarosite, some lead white, indigo, and an orange-fluorescing red lake; only purpurin was detected by LC/MS. The pink paint from the mummy shroud (see fig. 3.9) was found to contain gypsum, some calcium carbonate (calcite), small amounts of iron oxides, and red lake. LC/MS analysis (not shown) detected pseudopurpurin, with smaller amounts of alizarin and purpurin and, possibly, rubiadin. Of the several samples from mummy portraits that have been successfully analyzed by this same LC/MS procedure, pseudopurpurin has most often been the only HA detected. Although it is only speculation, this result could indicate (as discussed above) that the source may not have been R. tinctorum. In mummy portraits, madder appears to have been the major pigment used for pink draperies, just as the actual fabrics depicted were likely most often dyed with madder. Purple fabrics in mummy portraits were, it appears, often painted with a mixture of madder and indigo, the same mixture probably commonly used to dye fabrics purple. Given the ready availability and low cost of madder, it is not surprising that it was so prevalent in dyed fabrics and painted representations of those same fabrics.38 The APPEAR database contains more than fifty paintings in which madder is said to be present, and the vast majority of these identifications is based solely on UVL imaging.39 In addition to serving as a major pigment in fabrics, madder also is frequently found in highlights on faces and hands; in some portraits, madder is also noted as a major pigment in flowers of and , or representing wine in glasses. Noninvasive analysis can add more certainty than observation of fluorescence; instrumental analysis of samples may provide specific identifications of HAs and provide more insight into the lake substrate. As analysis and noninvasive examination techniques continue to improve, so will knowledge about ancient lake pigments. The matter of madder (and other natural red colorants from insect or other plant sources) is a subject about which there is more to be learned. Figure 3.6

Figure 3.6 Figure 3.7

Figure 3.7 Figure 3.8

Figure 3.8 Figure 3.9

Figure 3.9 Figure 3.10

Figure 3.10 Figure 3.11

Figure 3.11 Figure 3.12

Figure 3.12 Figure 3.13

Figure 3.13Notes

| words