5. Egyptian Blue in Romano-Egyptian Mummy Portraits

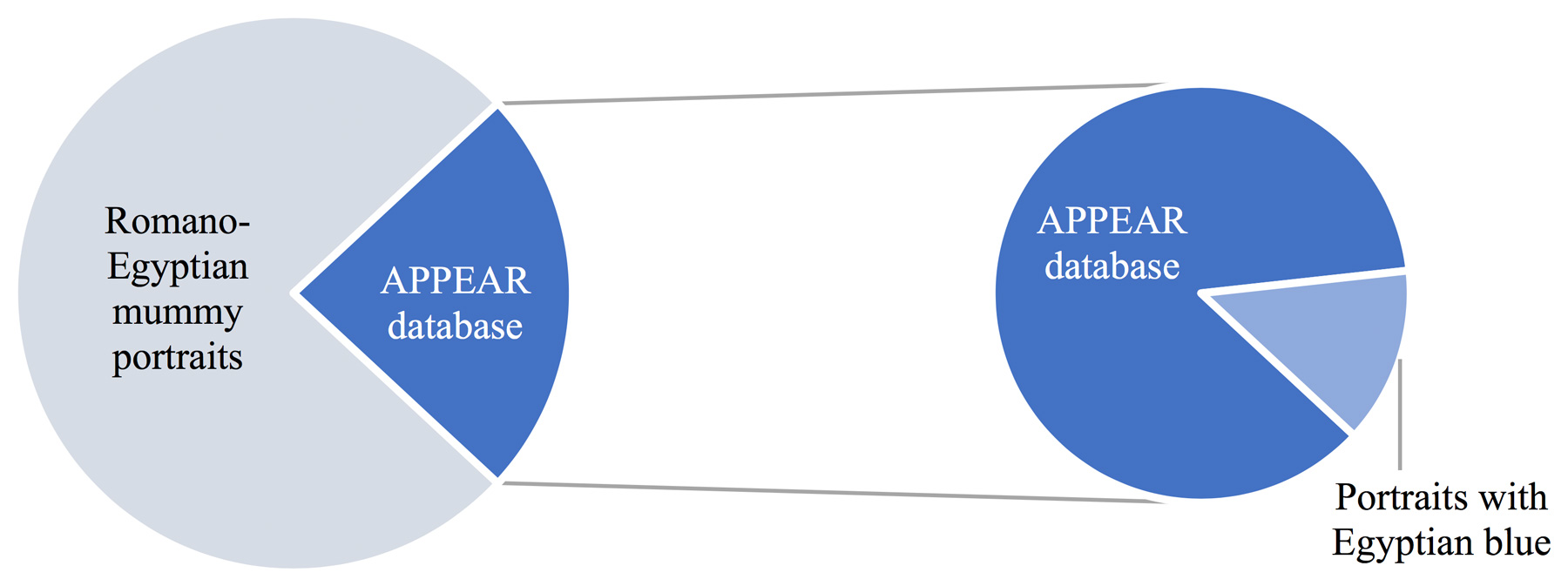

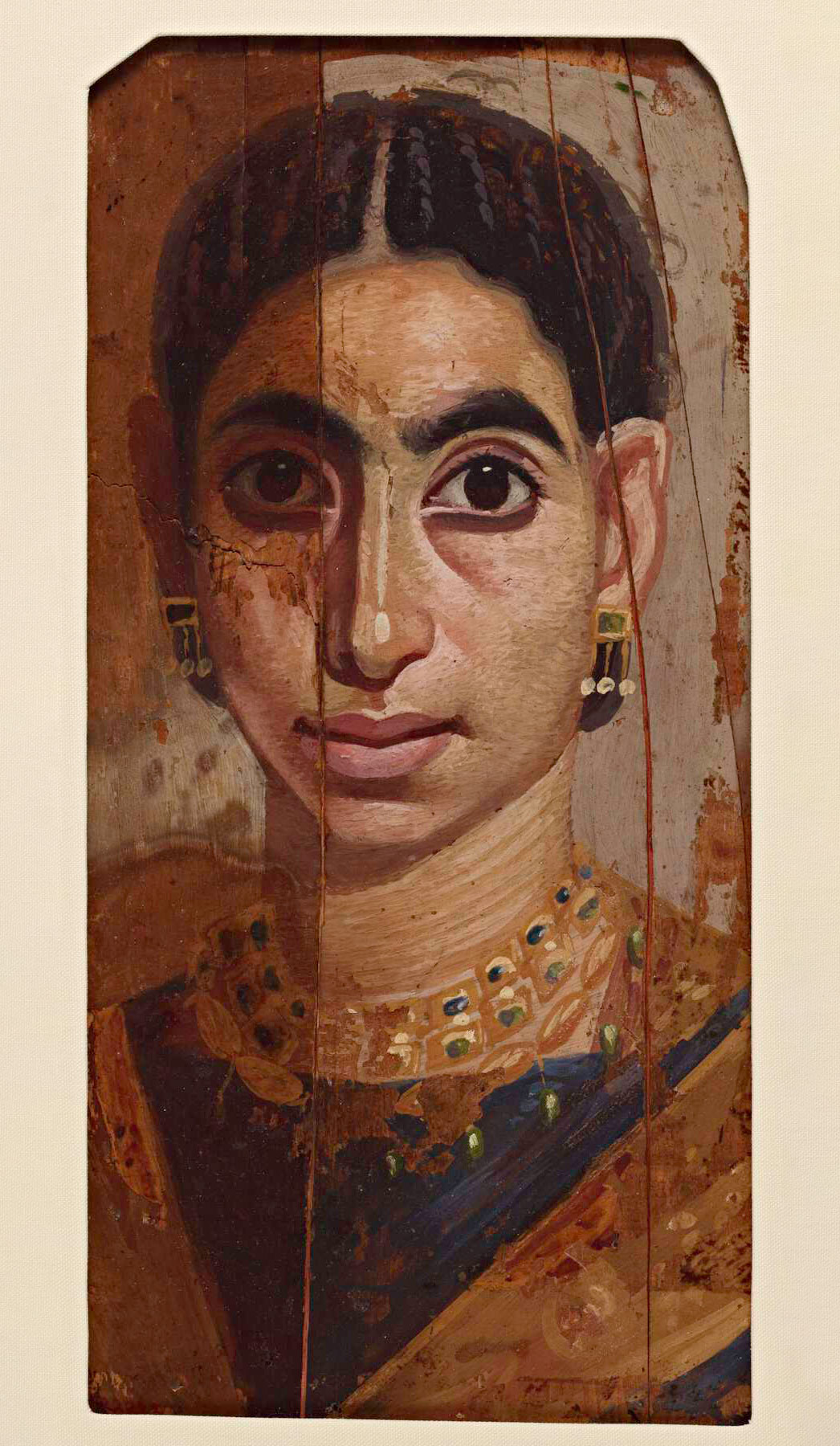

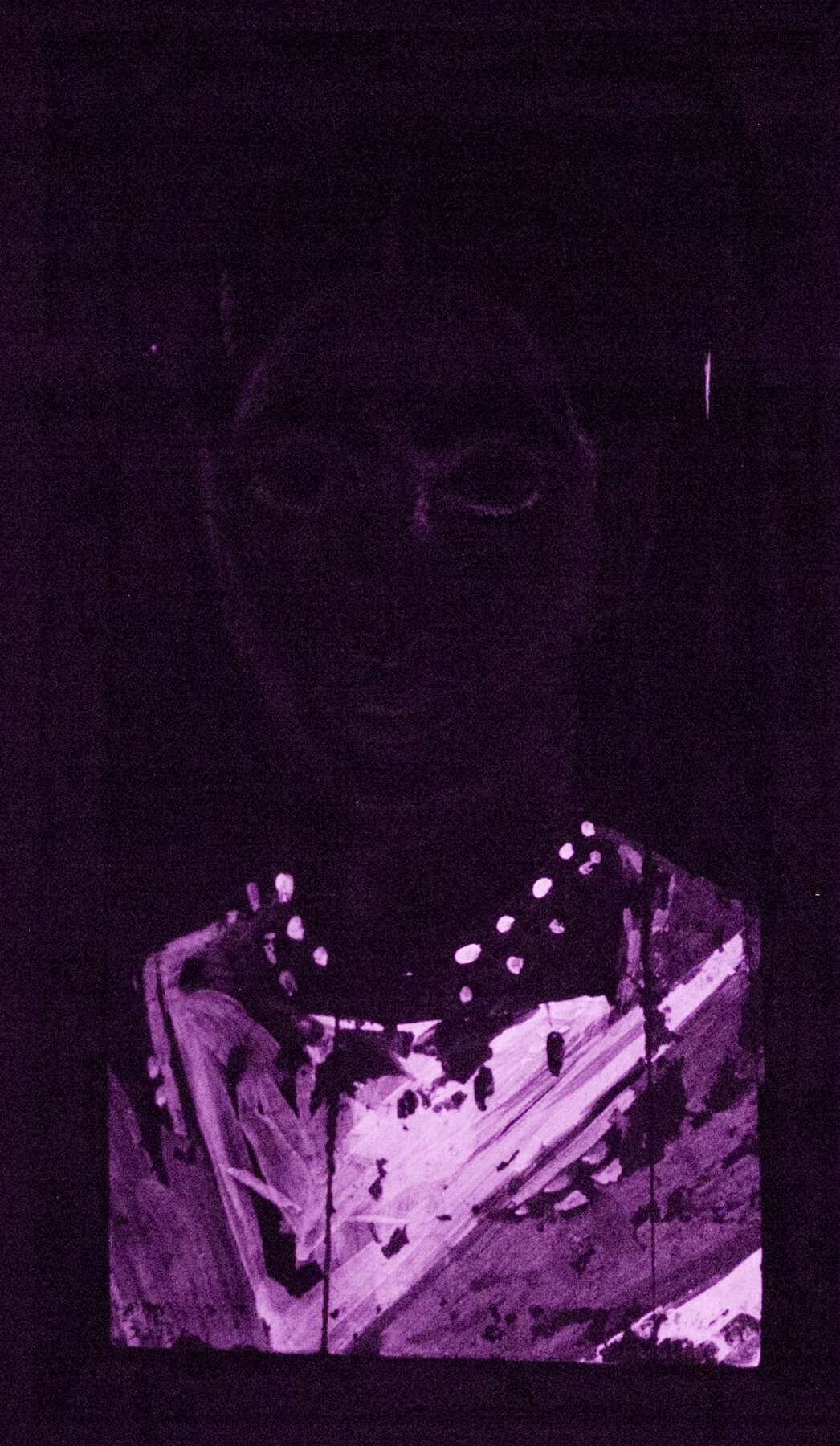

Two blues were used in Romano-Egyptian mummy portraits: , an artificial copper-based , and , a natural dye.1 Research conducted by APPEAR project participants has demonstrated that at least 20 percent of the mummy portraits were made using one or the other (or both), shedding new light on the production process of mummy portraits. The discovery of significant amounts of Egyptian blue on the so-called Mummy Portrait of a Woman (figs. 5.1 and 5.2) at the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts (Cantor Arts Center) confirmed trends visible in portraits from other collections and raised larger questions about patterns of use across find sites and time periods. This paper examines some of the results obtained by APPEAR participants and offers a preliminary discussion of how Egyptian blue was used in mummy portraits. The goal of this essay is to situate the use of the pigment in its broader artistic, social, and economic context(s), giving special consideration to its value and the range of meanings of blue in ancient sources. Such contextualization allows for a better understanding of Romano-Egyptian funerary portraiture and its place in the wider spectrum of ancient painting. Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1 Figure 5.2

Figure 5.2

Production of Egyptian Blue

Egyptian blue, a copper calcium silicate (CaCuSi4O10), is a glassy blue pigment with a hue ranging from light to dark, depending on the size of its grains, that is made by firing quartz, sand, lime, natron or plant ash, and copper or bronze at 900 to 1,000 degrees Celsius for more than 24 hours, probably in a cylindrical open vessel.2 It is the world’s oldest synthetic pigment, dating from at least the First Dynasty in Egypt, although an even earlier instance was found on a predynastic alabaster bowl at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.3 The latest production date of Egyptian blue is debated, but it has been found in Rome and Switzerland on wall paintings that date from the eighth to ninth centuries AD.4 In terms of geographic distribution, Egyptian blue has been found on objects around the Mediterranean and beyond—even as far as the Arctic Circle in the north of Norway, where it was used on a shield of the Bo people made around AD 250.5 The trade of the pigment is well attested in the Roman period, and it has been found with other pigments and goods in multiple shipwrecks, including Planier 3 and La Chrétienne M.6 Archaeological evidence for the production of Egyptian blue was uncovered at Memphis and Amarna in Egypt, Cumae in Italy, and Kos in Greece, while early authors mention the pigment was also produced in Scythia, Cyprus, and Spain.7 In ancient literature, three sources discuss Egyptian blue in detail: Pliny the Elder, Theophrastus, and Vitruvius, who refer to it as κύανος in Greek and caeruleum in Latin—two words that have broad semantic ranges and that should be translated carefully according to context.8 For art historians, the enduring popularity of Egyptian blue and its wide-ranging distribution offer privileged insight into technical and stylistic changes, both at a local and at a pan-Mediterranean scale, as the pigment was used in idiosyncratic ways that can be tracked across different time periods and regions.

Egyptian Blue in the APPEAR Database

Many APPEAR project participants, including the Cantor Arts Center, the British Museum, and the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, have detected Egyptian blue noninvasively on mummy portraits via several techniques, including .9 Developed by Giovanni Verri, this imaging technique relies on the fact that Egyptian blue has strong photo-induced near-infrared (NIR) luminescence; it displays a strong emission in the NIR range, with an emission maximum at 910 nanometers, when excited in the visible range.10 VIL can detect particles of Egyptian blue even when it is mixed with other pigments, covered by substances such as varnishes, or otherwise invisible to the naked eye.11 Beyond providing evidence for the presence and absence of luminescence, however, VIL images taken by APPEAR participants are usually not directly comparable because the equipment, capture conditions, and post-processing protocols of individual teams vary.12

At the time of writing (May 2018), approximately 284 paintings have been entered into the APPEAR database—a little less than 30 percent of the corpus of known painted mummy portraits from Roman Egypt.13 Few of these portraits display blue hues, except to render blue gems in jewelry (see figs. 6.9a and 5.1). Some portraits depict individuals wearing blue garments, usually or mantles (e.g., Berlin Antikensammlung 31161.26, Pushkin Museum 1a 5771). More rarely, portraits represent individuals with blue eyes (e.g., Pushkin Museum 1a 5771). It is therefore surprising that, so far, at least forty-four portraits in the APPEAR database have been found to display the VIL characteristic of Egyptian blue (fig. 5.3).14 While this tally is much smaller than that of other pigments, such as ochre (found on at least seventy-two portraits) and (found on at least sixty-six portraits), it is likely to rise in the future as institutions continue to analyze their portraits and share their results on the database.15 In total, at least forty-seven mummy portraits are now known to have Egyptian blue—forty-four portraits in the APPEAR database and three portraits at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (C.G. 33232, 33240, 33267).16 Based on how the pigment has been used on the portraits, we can safely assume that its inclusion was deliberate. Because the APPEAR project is ongoing, and participating institutions hold the rights to their VIL images, the following section will discuss results in general and preliminary terms—individual publications must be consulted for more details.

Date, Provenience, and Style

The forty-seven portraits with Egyptian blue vary in date, , and style. In terms of date range, it is now clear that the pigment was used throughout the whole period of production of painted mummy portraits, from the mid-first century AD, as in the Menil Collection’s late portrait (MFAH 2009.16) on which the pearl earrings are highlighted with Egyptian blue, to at least the mid-third century AD, as in the Cantor portrait (see figs. 5.1 and 5.2).

In terms of provenience, of the forty-seven portraits with Egyptian blue, fifteen are from , eleven from , seven from Tebtunis, one from , one possibly from Saqqara, and one possibly from ; eleven have no known . This distribution indicates that Egyptian blue was used on portraits found at all the major find sites and suggests that the pigment was used in all of the known production centers of funerary panel paintings.

All the portraits on which Egyptian blue was found so far were painted on wood panels, with the exception of a work from the Ashmolean Museum (AN1913.512). Interestingly, the portraits with Egyptian blue were more likely to be executed in : forty-one are made with a wax-based binder (87%), whereas only five are (10.6%) and one is of unknown media (2%). In the known corpus as a whole, at least 618 portraits are in encaustic (59%), 398 are in tempera (38%), and 25 are unknown (2.4%); therefore, there seems to be a correlation between the use of Egyptian blue and wax binders (fig. 5.4). These preliminary observations warrant further investigation by APPEAR participants.17 Figure 5.4

Figure 5.4

Uses of Egyptian Blue in the Mummy Portraits

Figure 5.5 lists the ways, in order of frequency, that Egyptian blue is used in the forty-seven panel paintings that contain it. Three salient points emerge from this list.18

(1) Egyptian blue is most often mixed with other pigments and rarely achieves the hue we would consider blue, which, as mentioned above, is mostly absent from the portraits except in the few instances when blue gems, eyes, or garments are depicted.

(2) Egyptian blue is often mixed with pigments and to create green, white, purple, pink, rosy beige, black, and brown, although the most frequently found hues are grayish and beige-hued white.

(3) Clear patterns of use are visible, whereby Egyptian blue is most often used in backgrounds and to model faces, both of men and women. Uses of Egyptian Blue Instances Shading of cool flesh tones 31 Background (gray) 27 White/grayish white garments 13 White of eyes 10 Contour of the face 9 Dark hair highlights 9 Purple/pink garments 8 Pink of lips 5 White pearls 5 Purple clavus 3 Blue gems 2 Blue garment 2 Hazel irises 2 Green gems 2 Green leaves 1 Pupil highlight 1 Pink garland 1 Gray-white hair 1 Uses of Egyptian Blue Instances Shading of cool flesh tones 31 Background (gray) 27 White/grayish white garments 13 White of eyes 10 Contour of the face 9 Dark hair highlights 9 Purple/pink garments 8 Pink of lips 5 White pearls 5 Purple clavus 3 Blue gems 2 Blue garment 2 Hazel irises 2 Green gems 2 Green leaves 1 Pupil highlight 1 Pink garland 1 Gray-white hair 1

Interpretation

The use of Egyptian blue in mixtures rather than on its own should not necessarily be taken as evidence that the artists or commissioners of the mummy portraits favored the classical / early Hellenistic tetrachromatic palette of red, yellow, white, and black, as has been proposed.19 All the ways in which Egyptian blue is used on the mummy portraits have parallels in other artistic media from the Roman period, including painted statuary and wall paintings, which places the portraits firmly in a Roman artistic tradition and suggests that strong material, technical, and aesthetic ties united painting practices across the Mediterranean in this period.20

The popularity of Egyptian blue in the mummy portraits may partly be explained by its affordability. Despite frequent suggestions that the pigment was expensive because of its complex manufacturing process, the archaeological and literary evidence indicate otherwise. The pigment was often used to decorate objects of little monetary value, such as mass-produced terracotta figurines, confirming that the pigment was neither rare nor prohibitively expensive. In fact, Egyptian blue is the third most commonly found raw pigment in Pompeii, right behind and and far ahead of other pigments.21 Lucian uses the Greek word for Egyptian blue, κύανος, in a dialogue in which Lycinus admonishes Lexiphanes for his oratory style, telling him it resembles figurines sold in the agora, stained (κεχρωσμένος) with blue (κύανος) and red (μίλτος) and made of fragile (εὔθρυπτος) clay inside.22 The comment is meant to be derogatory, likening blue and red pigments with cheap efforts to dress up a worthless core.

In the 70s AD, Pliny the Elder mentions a price range of eight to eleven denarii per pound of caeruleum, Egyptian blue, depending on the pigment’s quality—almost exactly the same price as good red ochre, sinopis, which sold for twelve denarii per pound, and about half the price of indigo, indicum, which cost seventeen to twenty denarii per pound.23 Naturally, these costs fluctuated according to demand, availability, and inflation. The price of Egyptian blue had increased tenfold by AD 301, when the Edict of Diocletian set a maximum price of one hundred fifty denarii for a pound of cyanus vestorianus, Vestorian or Egyptian blue.24 Although this figure seems dramatically higher than Pliny’s, inflation and the devaluation of currency over this 225-year period means that the actual value of the pigment had gone down by as much as 80 to 90 percent, making it quite affordable.25 These prices are relatively consistent with the pigment bills found on papyri. It is interesting to note that the price ranges indicate there were degrees of pigment quality, and that the price varied accordingly. Although it has not been possible to detect variations in the quality of Egyptian blue used in the mummy portraits so far, the ancient sources cited above attest that it was relatively inexpensive during the period of production of mummy portraits.

Beyond the affordability of the pigment, there may have been material and cultural reasons for the use of Egyptian blue in the portraits. The results obtained by APPEAR participants demonstrate that in at least ten instances, Egyptian blue was mixed with other pigments to represent , or purple tunics (e.g., Cairo Egyptian Museum C.G. 33240 and British Museum EA74832).26 This trick is described by Pliny and Vitruvius, who claim that caeruleum (Egyptian blue) could be mixed with purpurissum (a red dye) to create purple.27 Interestingly, indigo—despite its different optical properties—is also frequently mixed with organic red colorants to obtain similar results, as has been found in the clavi of three of the portraits at the Hearst Museum and in the garments of eight portraits at the Getty.28 The choice of one blue pigment over the other in mixtures does not seem to indicate that the other pigment was unavailable; indeed, the Tebtunis portraits that have indigo in the clavi also have Egyptian blue in the backgrounds. The frequent use of indigo in clavi therefore seems deliberate, perhaps following a pattern whereby the artists tended to prefer painting materials that were close to the real-life objects they were meant to depict: gold leaf to represent gold jewelry, natural dyes for garments, Egyptian blue for gems, and lead white, which could be used for makeup, to model faces. This association between everyday materials and the choice of pigments is particularly visible in the use of madder lake, which in dye form is frequently used on textiles, to depict pink garments in the mummy portraits.29 Choosing painting materials according to how closely they evoked their real-life counterparts may have been a strategy to heighten the portraits’ mimetic impact.

The use of Egyptian blue in flesh tones is perhaps the most interesting of all. It is more often found in female portraits, where skin tones are traditionally ruddier (eighteen instances in female portraits to thirteen instances in male portraits). In his Natural History, Pliny tells us that a pigment named anularian white was used for giving a brilliant whiteness to female figures. According to him, this pigment was prepared from a chalk combined with the glassy paste “[that] the lower classes wear in their rings; hence it is, that it has the name anulare.”30 This passage is traditionally interpreted as referring to makeup that women would wear, similar to the lead-based ceruse Pliny describes in 34.54.31 However, it is possible that this glassy paste may, in fact, be Egyptian blue, as its manufacturing process is very close to that of glass, and it could be molded to fit into jewelry instead of a gem.32 In this case, Pliny’s anularian white could be the white-and-blue mixture used to create highlights on the faces of some mummy portraits.33 It is notable that mixtures of Egyptian blue and chalk (usually calcite and aragonite) were found in Pompeii; color merchants likely sold them pre-mixed on account of their popularity.34

The use of Egyptian blue in the flesh tones of mummy portraits may have something to do with the pigment’s optical brightness, which had a special significance in an Egyptian funerary context. In the Pharaonic period, blue was associated with the sun, life, and immortality; in art, it was often used to depict the flesh of particular deities, such as Amun, while in literature, blue highlights in dark hair signified great beauty. Lorelei Corcoran notes that blue is associated consistently with “the scintillating effect” it produces, which “imbues an inanimate work of art with a sense of living presence,” and concludes that the glassy particles in Egyptian blue were probably appreciated for their ability to reflect light.35 Classical authors also often refer to the shimmery quality of blue. For instance, in the Timaeus, Plato defines κύανος as a mix between black, white, and τον λαμπρrόν (shininess).36 The use of blue in flesh tones also had a symbolic meaning in classical literature, in which blue often refers to youth or to a divine-like appearance, as in Pharaonic art. Zeus, Poseidon, and other gods are described as having blue hair and beards, while their skin is often said to have a blue quality to it—probably referring more to the shimmery quality of blue than its actual hue. In the Odyssey, Athena alters Odysseus’ appearance upon his return to Ithaka, making his hair and skin κύανος (blue/shimmering), thereby elevating him above his mortal self and causing his son, Telemachus, to wonder if he is a god.37

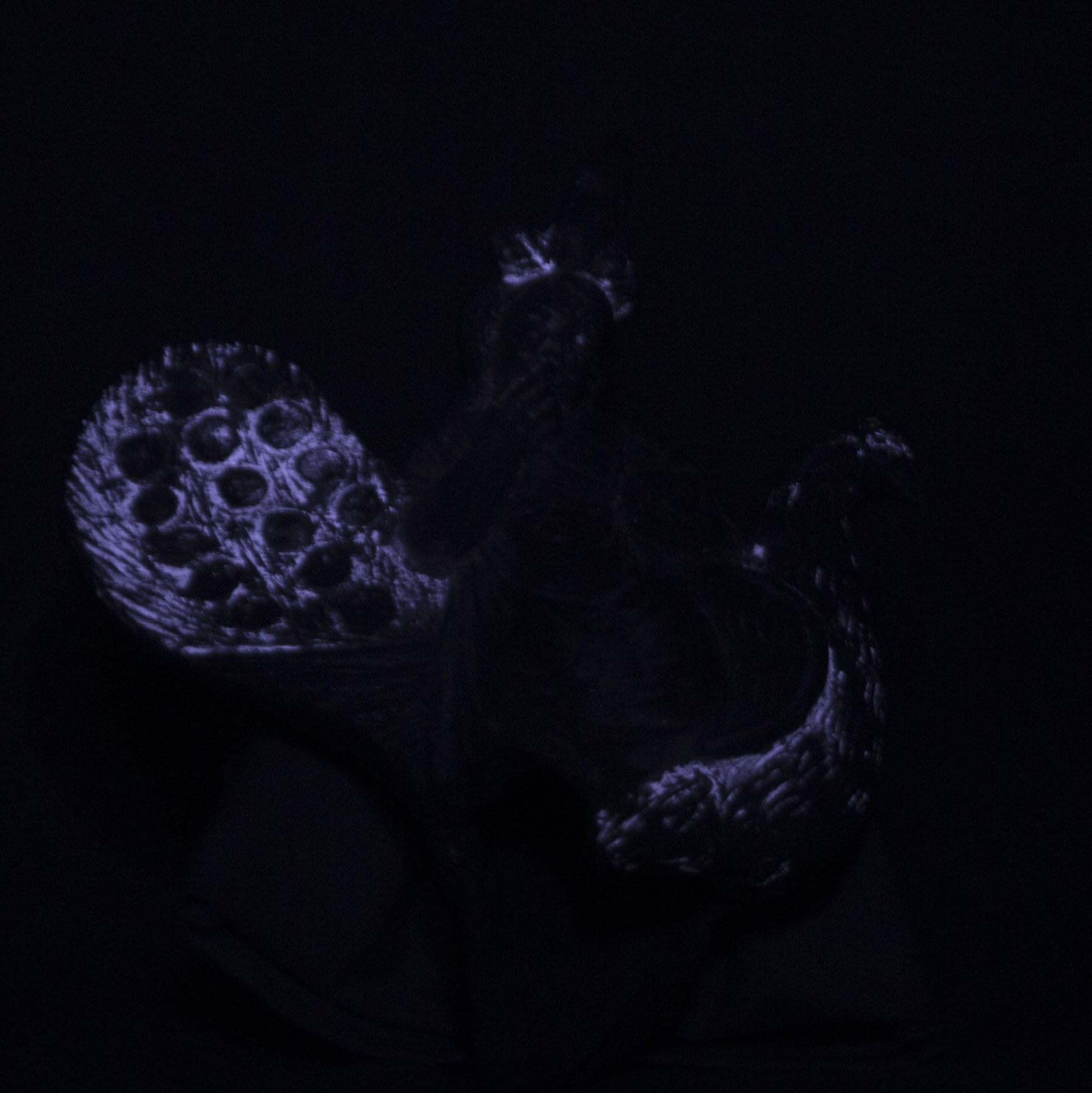

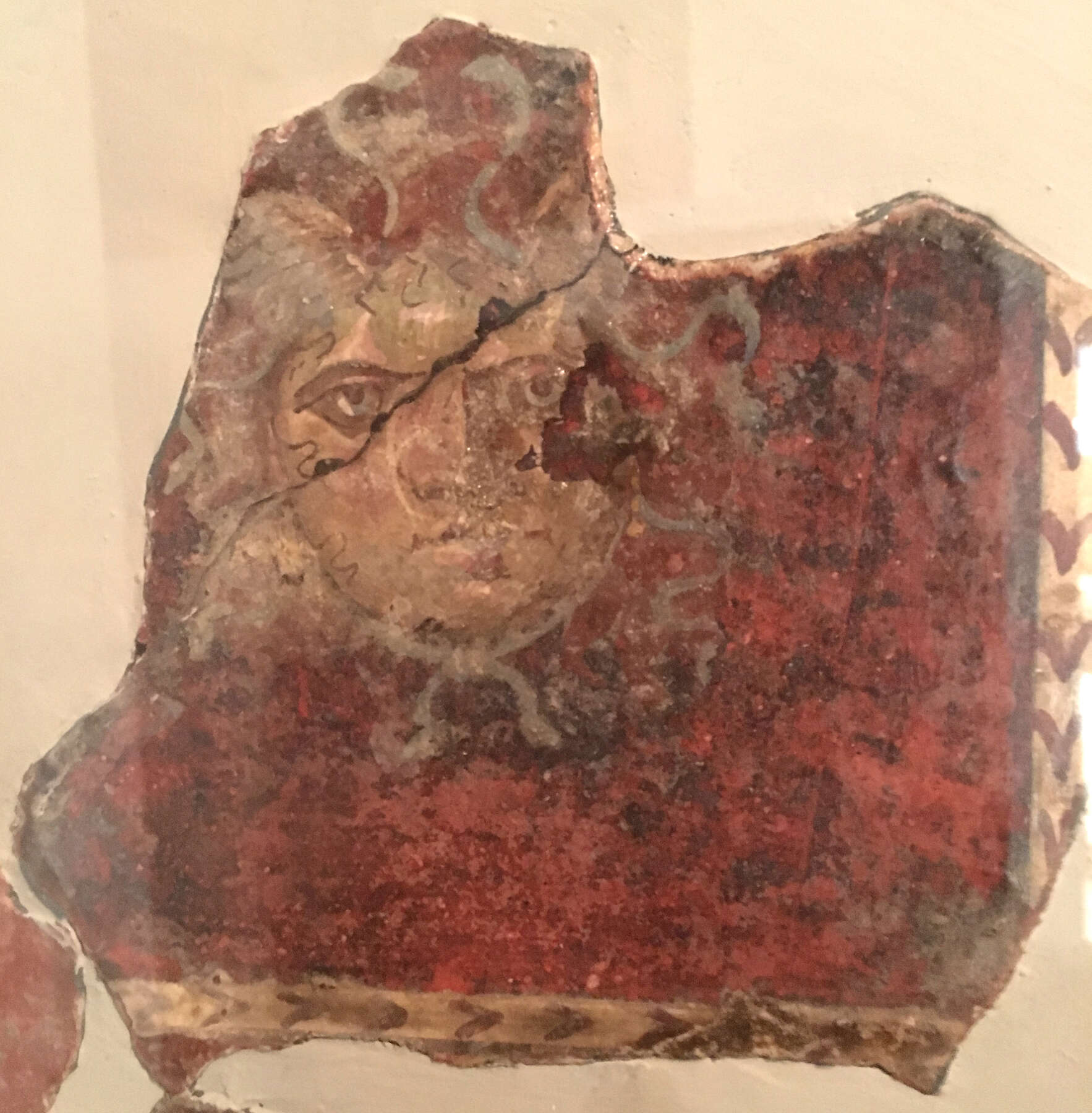

Mixed with white, Egyptian blue also contributes to giving a “liquid” quality to the white of the eyes of certain mummy portraits, including British Museum EA74832, Phoebe A. Hearst Museum 6-21380, and Cairo C.G. 33232, a technique that has been observed in the eyes of statues from the classical period onward. The mixture of Egyptian blue and white may serve to achieve an effect akin to the epithet associated with Athena, γλανκῶπις, which is sometimes translated as “blue/gray/green-eyed” but most likely means “flashing/bright-eyed.”38 It is notable that the technique was frequently used on gorgoneia, including on a Campanian wall-painting fragment at the Allard Pierson Museum, considering that their eyes were notoriously fearsome (figs. 5.6a and 5.6b; figs. 5.7a and 5.7b). Eyes that are moist and luminous—two effects achieved by adding Egyptian blue—are extolled by ancient authors as signifying beauty and intelligence.39

Figure 5.6a

Figure 5.6a Figure 5.6b

Figure 5.6b Figure 5.7a

Figure 5.7a Figure 5.7b

Figure 5.7bThe naturalism achieved by using Egyptian blue in flesh tones and for the whites of eyes may have been an end in itself, as one of the primary goals of mummification was to make the body recognizable to the soul (the ba and the ka) of the deceased after death. The use of a blue pigment in flesh tones also finds strong echoes in literary and artistic depictions of both Greek and Egyptian gods as having blue/shimmering faces and eyes, which suggests that the pigment allowed the deceased to present an idealized version of themselves, ready for the journey to the afterlife and having already acquired the divine qualities of κύανος skin and hair. After all, in Egyptian beliefs, mummy masks served to protect the deceased, grant them the ability to see and speak in the afterlife, and make them “beautiful of face among the gods.”40 While the artists of the mummy portraits might not have had Pharaonic art or Homeric texts in mind when using Egyptian blue, their choice may have been influenced by certain subtle cultural constructs, which shaped their understanding of the symbolic properties of the pigment.41

Conclusion

The APPEAR project provides an extraordinary opportunity to reexamine mummy portraits and compare analytical results obtained by multiple institutions. The data gathered by APPEAR participants can then be interpreted through the lens of archaeological, literary, and documentary sources to better understand the use of individual pigments and also to reinterpret ancient sources through material evidence.

This close examination of the VIL results obtained by APPEAR participants has revealed that Egyptian blue was used in portraits that were found in all the major find sites and that date from the entire production period of mummy portraits. VIL results also confirmed that the pigment was used in idiosyncratic ways: in flesh tones, garments, and eyes. Ancient sources suggest that the pigment may have been popular on account of its affordability and optical properties, which allowed painters to obtain the cool shades characteristic of the naturalistic style of the portraits. A closer examination of literary sources reveals that it is also likely that the pigment was prized for its shining/shimmering quality, which possessed strong associations with the divine. In this context, the use of Egyptian blue in the mummy portraits allowed painters to reproduce reality more closely and brought a symbolic potency to the portraits, perhaps in an attempt to help the deceased access the afterlife.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible thanks to the support of Susan K. Manganelli, Samantha Li, and Maria-Olivia Stanton-Davalos at the Cantor Arts Center Art+Science Learning Lab and to the staff at the Allard Pierson Museum, who allowed me to examine objects in their collection in 2017. Sincere thanks are also due to the editors and to the reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Notes

- . ↩

- ; . ↩

- ; . ↩

- . As early as the sixth century AD, authors display confusion as to how the pigment was made. Isidore of Seville mentions it was made of sand and natron with the optional addition of a Cypriot pigment called cyprium (Isid., Etymologies 19.17.14). Later instances include an eleventh-century wall painting in Spain and a 1524 painting of Saint Margaret by Giovanni Battista Benvenuto. These instances are generally explained as reuses of pigment samples, although some scholars believe the technology to make Egyptian blue was not lost, just extremely limited and localized. See ; . ↩

- . ↩

- ; . ↩

- ; ; ; ; Pliny, Natural History 33.57. ↩

- Pliny, Natural History 33.57; Theophrastus, De Lapidibus 55.1–12; Vitruvius, De Architectura 7.11. ↩

- ; Dyer and Newman, this volume. ↩

- , ; ; . ↩

- , ; , 220. For more examples, see ; . ↩

- The filters used by APPEAR project participants for VIL include the Hoya R72, Peca 904, Peca 908, Schott RG830 longpass filter, and XNite850—all of which have slightly different cutoffs. This, along with exposure time and the intensity of light sources, has an impact on the luminescence that can be detected by converted cameras. One step in the direction of standardization is the British Museum’s 2013 CHARISMA protocol. See . ↩

- For an almost complete catalogue, see . ↩

- The number of portraits that were tested but found to contain no Egyptian blue is unknown, since not all participants upload negative results to the database. ↩

- APPEAR database, as of November 2018. ↩

- The three portraits in Cairo were part of a group of ten portraits examined by the author in February 2017. ↩

- This correlation is also found in documentary evidence. A Ptolemaic-period bill for the painting of a house in the Fayum, P.Cair. Zen. 4 59763, mentions the price of (κηρός) and of pigments including lead white (ψιμύθιον), yellow ochre (ὤχρα), red ochre (μίλτος), and Egyptian blue (κύανος). A bill from Oxyrhynchus, HGV SB 14.11958, mentions fees to renovate a temple, including the prices of pigments, notably Egyptian blue, as well as sponges, pumice stones, and wax. This juxtaposition suggests that Egyptian blue was often used in conjunction with wax outside of mummy portraits, with wax used either as a binder or as a protective coating for wall paintings, as described by Vitruvius in De Architectura 7.9.3–4. ↩

- If Egyptian blue appears on a single portrait in multiple places—for instance, in a green gem and in a pink tunic—it is counted as two different instances. It is important to note that hues may have altered with time because of chemical interactions between pigments and , substrate, or environmental pollutants. ↩

- , 820. For a discussion of the contradictions in the sources considering this palette, see . ↩

- , 133; and ; , 1019. ↩

- See , 92. Forty-seven samples of raw Egyptian blue in a wide range of saturation were found in Pompeii in three forms: blocks, balls, and powders. ↩

- Lucian, Lexiphanes 22. ↩

- Pliny, Natural History 33.162; for indigo, see 33.163, 35.46. ↩

- Price Edict of Diocletian, De pigmentis 34. ↩

- , 90. ↩

- , fig. 5. ↩

- Pliny, Natural History 35.45; Vitruvius, De Architectura 7.14.1–2. ↩

- . ↩

- ; . ↩

- Pliny, Natural History 35.48. ↩

- , 260. ↩

- See, for instance, a number of blue frit bezel rings in the Fitzwilliam Museum and Egyptian blue beads found at Amarna, Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham, and Tell Brak (). For “glassy” substances being used to imitate gemstones, see Pliny, Natural History 37.22. ↩

- Anularian white is also described by Isidore of Seville, who says it brightens women’s cosmetics and is made from clay and “glassy gems.” Isid., Etymologies 19.17.22. ↩

- , 28. ↩

- , 42. ↩

- Plato, Timaeus 68c. ↩

- Homer, Odyssey 16.176. ↩

- , fig. 4c; . ↩

- E.g., Pseudo-Aristotle 807b.19. ↩

- Book of the Dead, Spell 151. ↩

- Petrie found a mummified woman whose head rested on a papyrus scroll containing a carefully transcribed copy of part of the second book of the Iliad (the “Hawara Homer”). , 24; Bodleian Library MS. Gr. class. a. 1 (P)/1-10. ↩