6. Multispectral Imaging Techniques Applied to the Study of Romano‑Egyptian Funerary Portraits at the British Museum

The British Museum (BM) holds a collection of about thirty Greco-Roman funerary portraits from Egypt dating from the first to the third centuries AD.1 Acquired between 1856 and 1994, they comprise eighteen female and twelve male portraits. Of them, two-thirds are classified as painted in (20) and just over a quarter in (8), with the use of both encaustic and tempera identified in the remaining examples. To date, these classifications have mostly been made by visual inspection alone, as so far very little analysis has been possible. In terms of supports, the portraits are mostly on Tilia, or lime wood, , which is in keeping with findings more generally, with a few painted on or linen cartonnage.2 More than half of the portraits are from (16), excavated by Petrie; a third are from (10) and reached the collection as a result of bequests by the Mond family to both the BM and the National Gallery, London; and the others (4) are from Thebes or Saqqara or of unknown origin.

In 2011 a condition survey of the BM’s portrait collection led to an extensive conservation campaign during which four portraits that had sustained considerable damage, as a result of being fixed to rigid supports since the 1930s, were removed from these wooden “pseudo-cradles.”3 As part of this endeavor, analysis was carried out to understand past interventions, which were largely undocumented and made for surfaces that were particularly difficult to interpret, even under a microscope. techniques were crucial to the understanding of these surfaces and in mapping the distribution of both restoration and original materials on the portraits.4

Since then, the BM has led in developing standardized methodologies for both the acquisition and the post-processing of multispectral images.5 These practices ensure that the images produced not only are consistent but adhere to a series of internationally established standards. Such guidelines greatly facilitate the reproducibility of the methodology by the user, but more importantly, enable the images produced by different users to be compared with each other and exchanged with others adopting this systematic approach. Within the framework of the APPEAR project this consistency is of crucial importance: collaborative scholarship via the comparison of images and data is a key element of the aims of the project and central to the creation of a useful and sustainable database.

In this essay current MSI methods in use at the BM, some of which were pioneered in-house,6 are described. In 2015 these techniques were applied to twenty-six portraits7 from the BM collection as part of the museum’s contribution to the APPEAR project. A summary of the results obtained is described using an innovative approach: the development of workflows that aid in the more standardized interpretation of these images and that enable new ways to interrogate the MSI data sets.

MSI Techniques

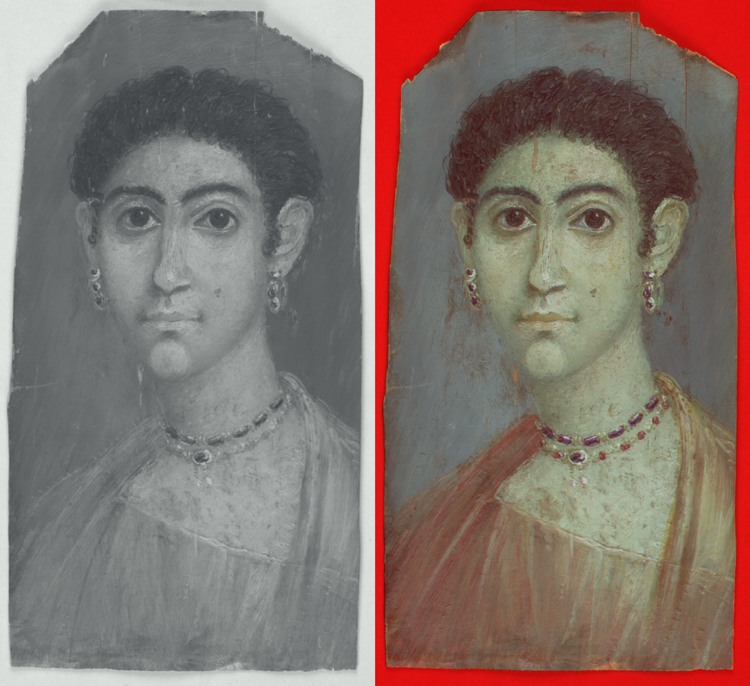

Multispectral imaging is a set of procedures used to observe an object by employing wavelength ranges that include and extend beyond the capabilities of the human eye. These techniques are increasingly being regarded as a powerful method with which to survey collections, as they allow the visualization and spatial localization of materials under different wavelengths of illumination. The resultant MSI sets often act as “maps” that highlight particular physical properties, allowing the objects to be viewed in a completely novel manner and emphasizing relationships between materials within the object and, often, between similar materials within a collection of related objects.

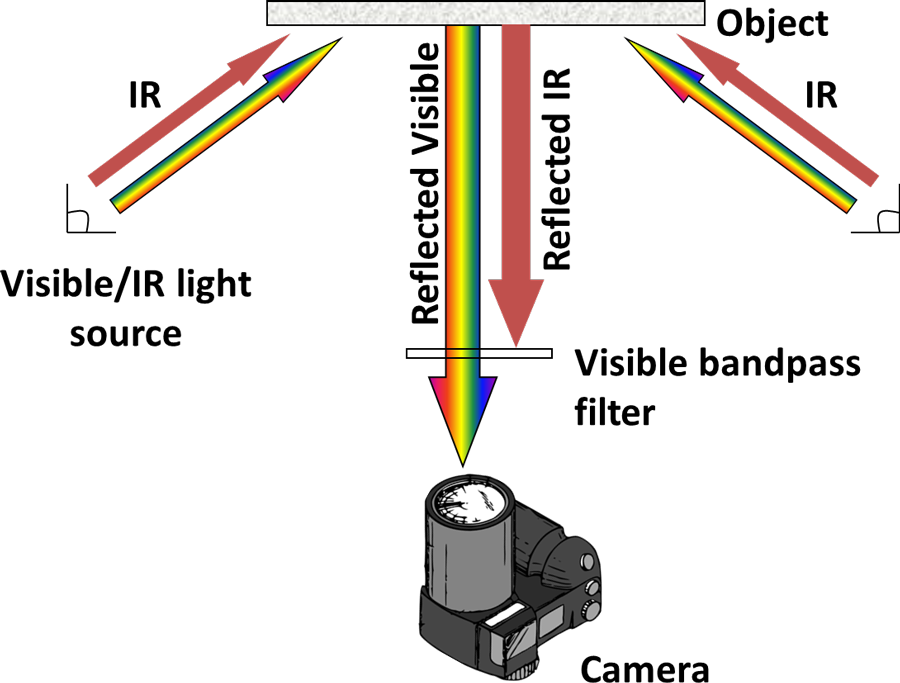

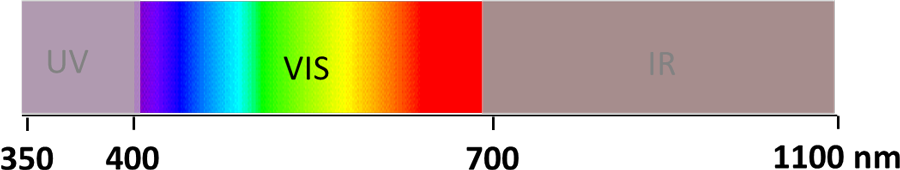

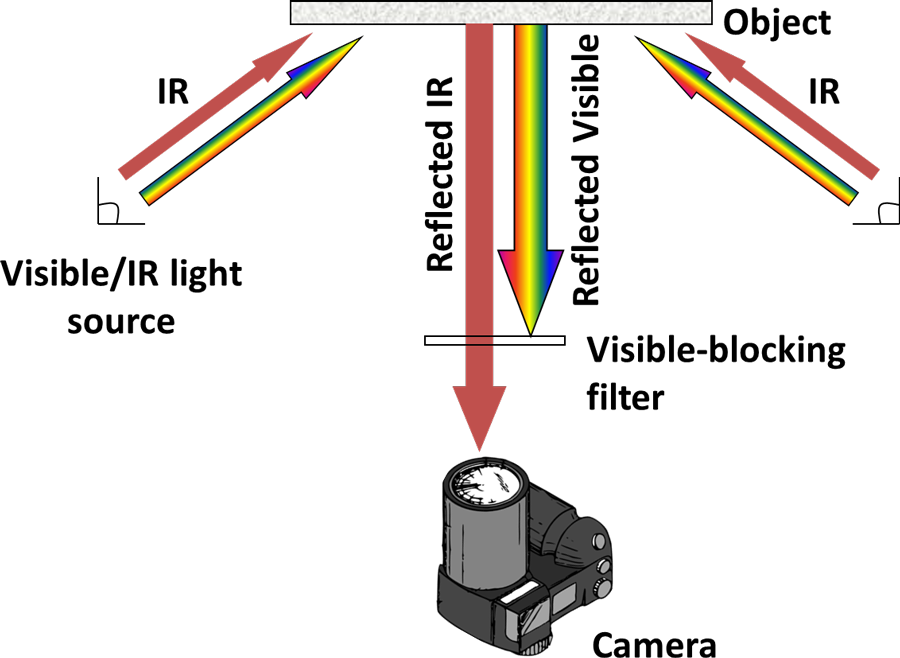

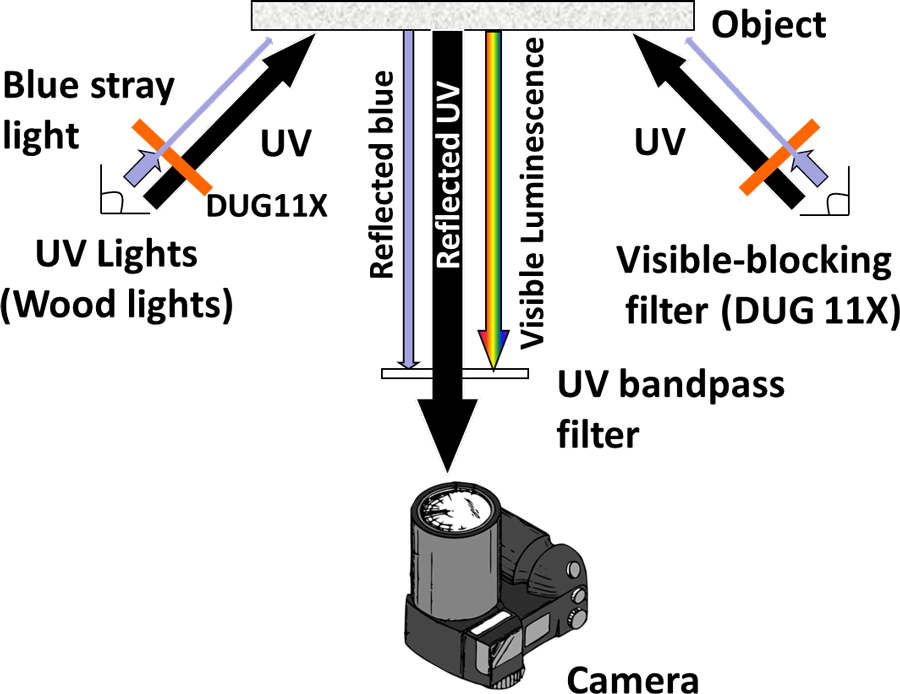

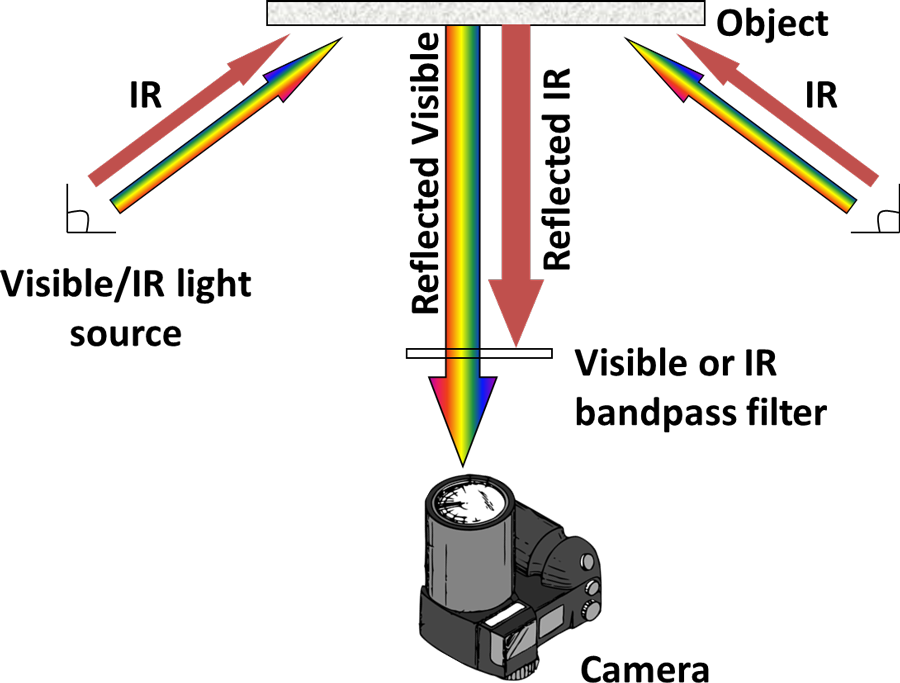

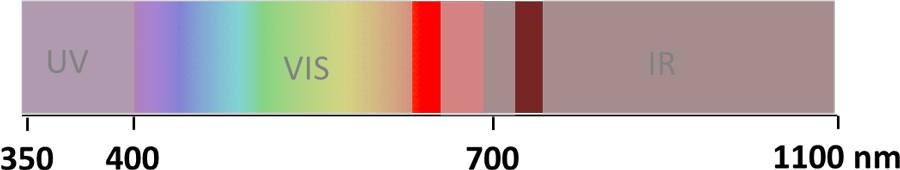

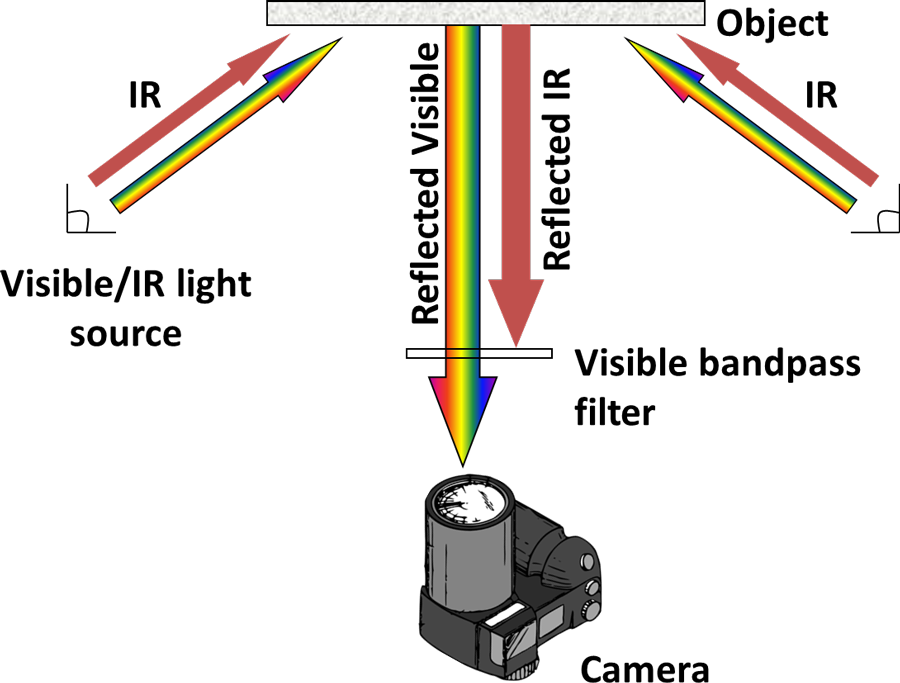

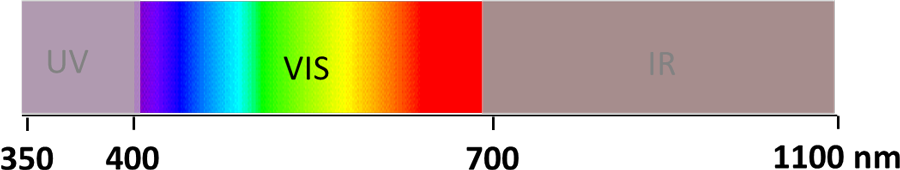

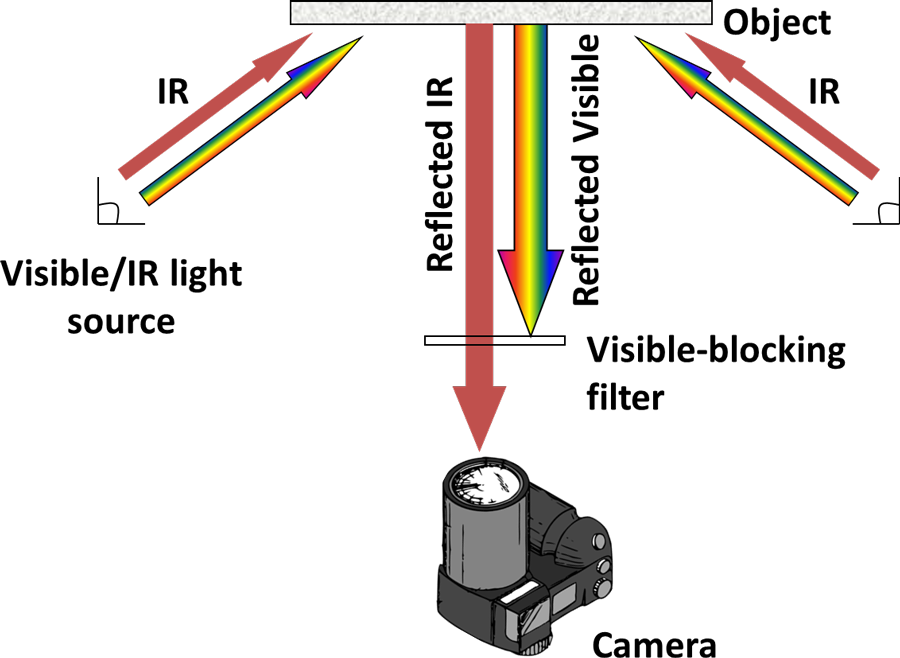

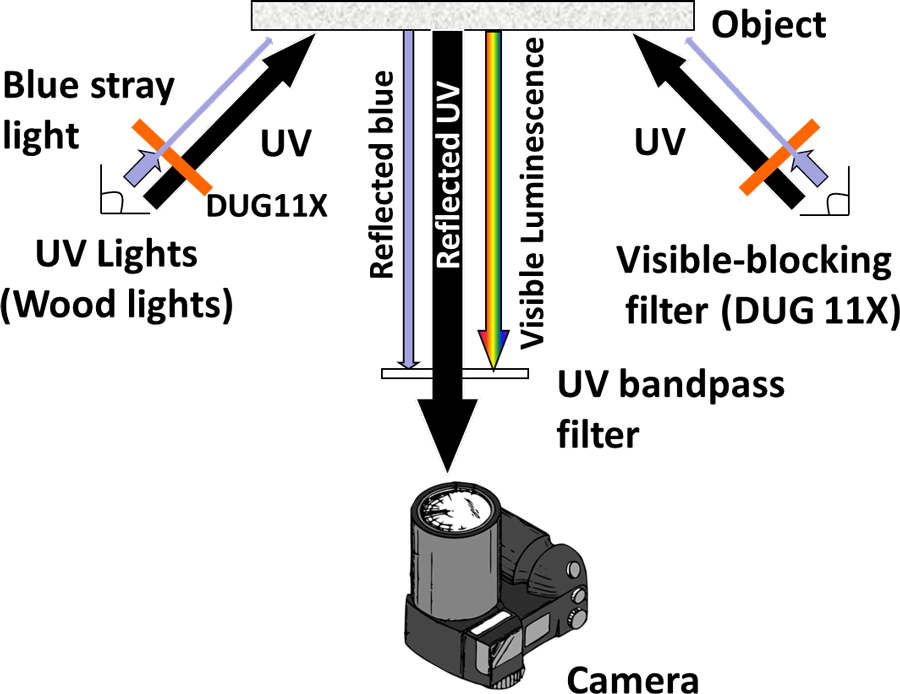

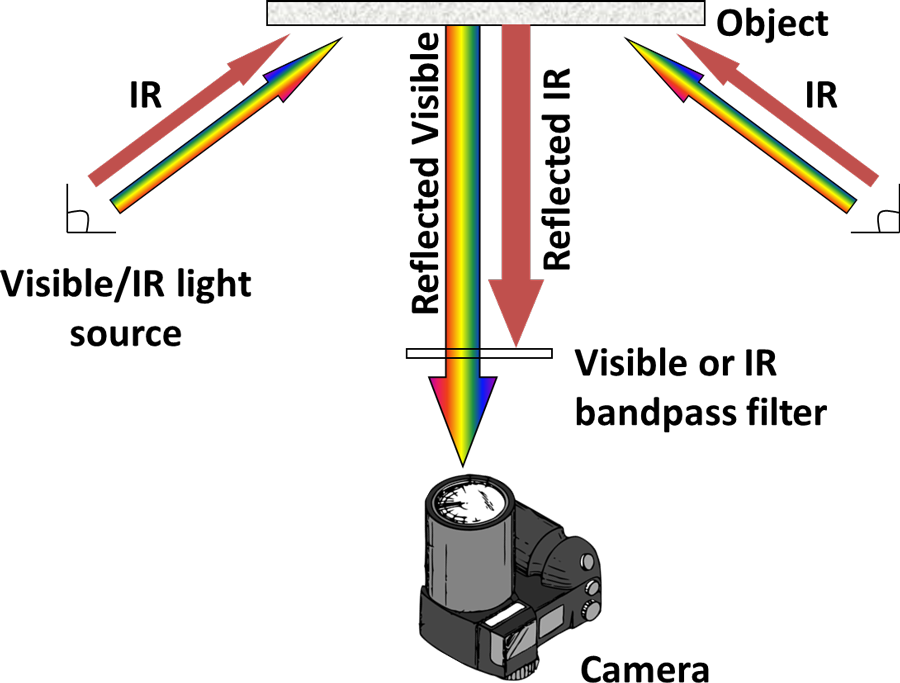

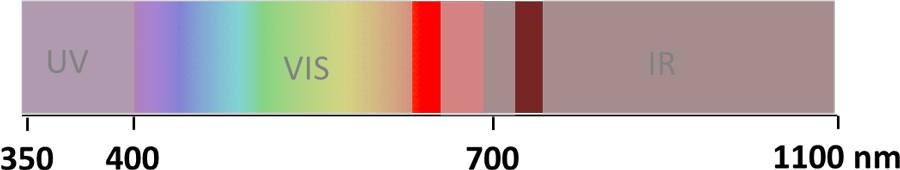

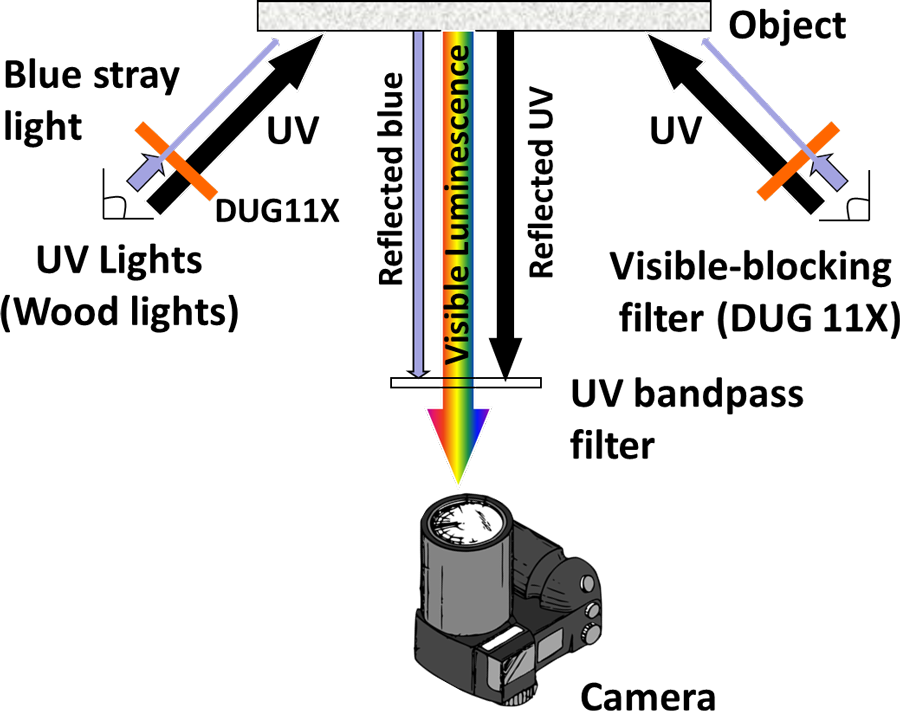

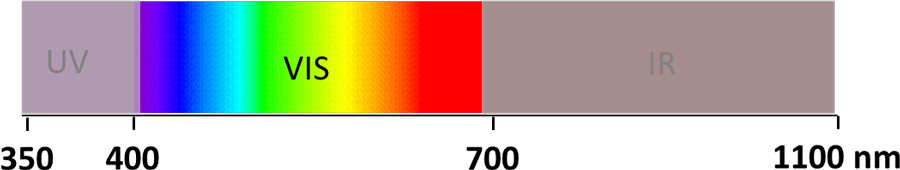

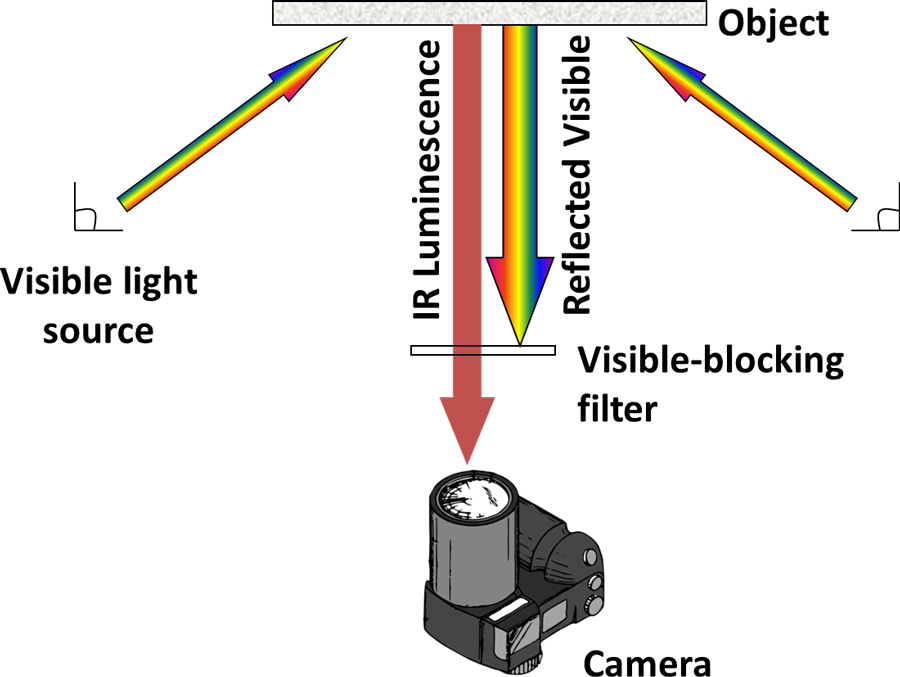

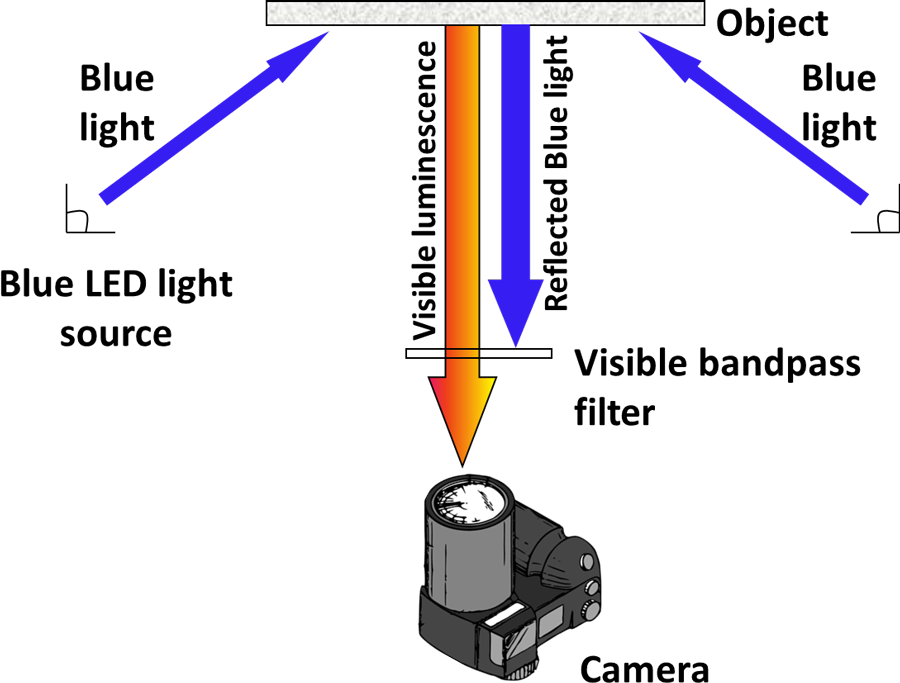

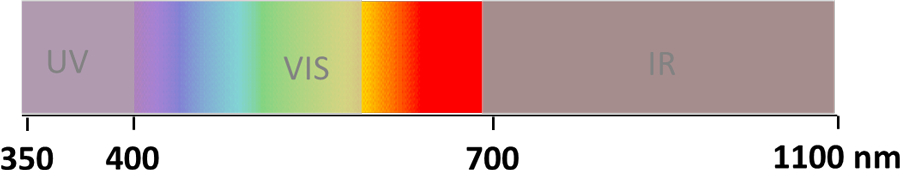

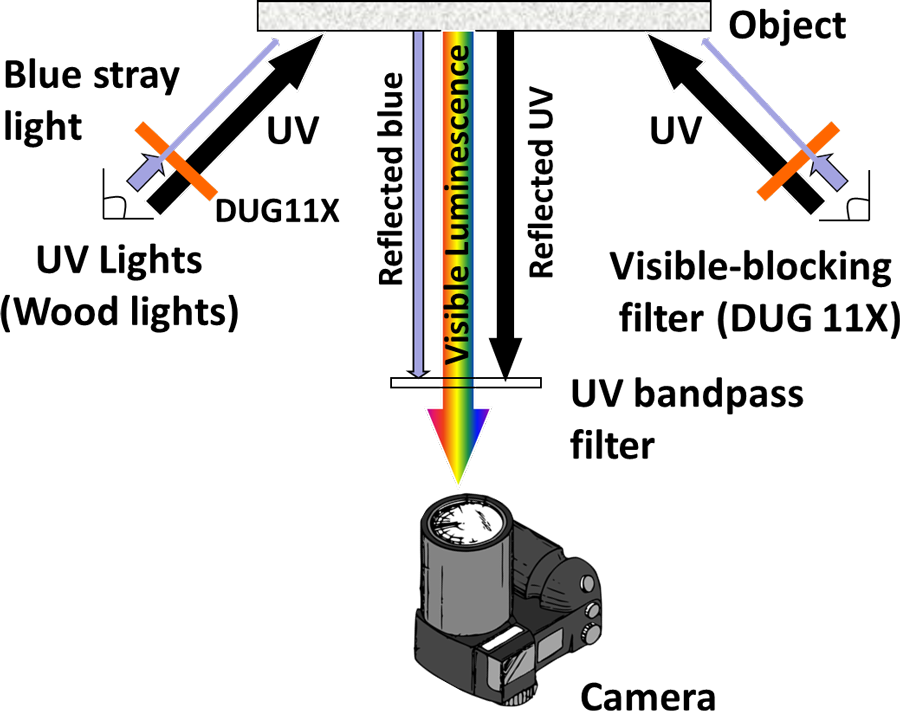

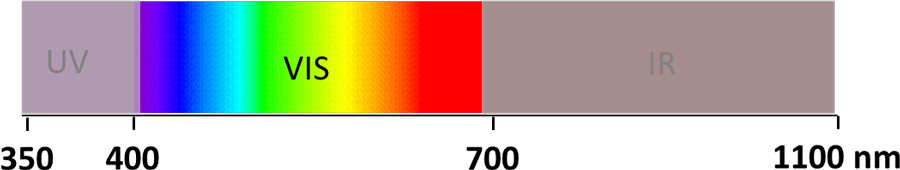

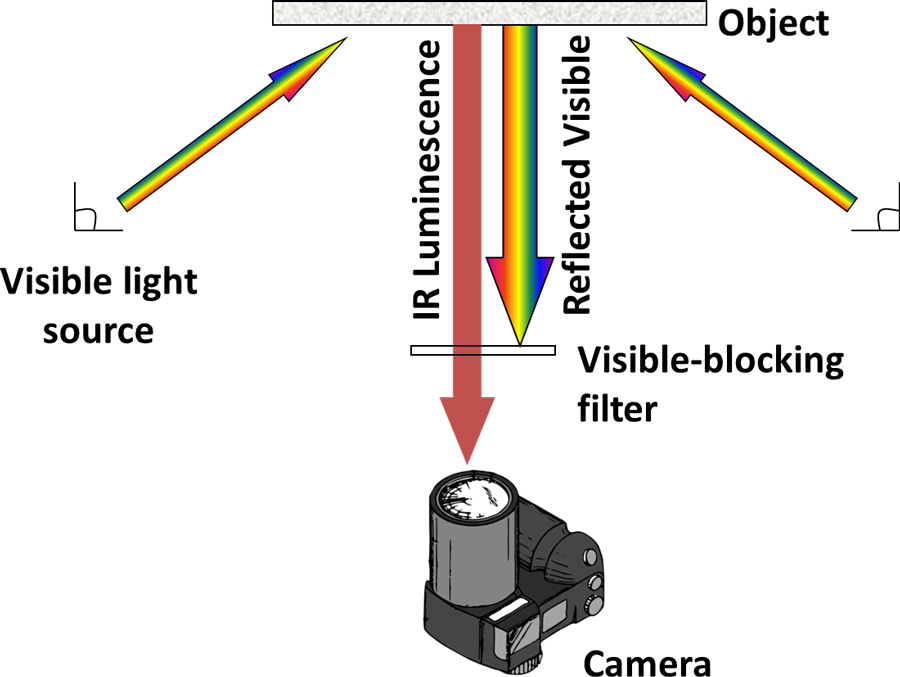

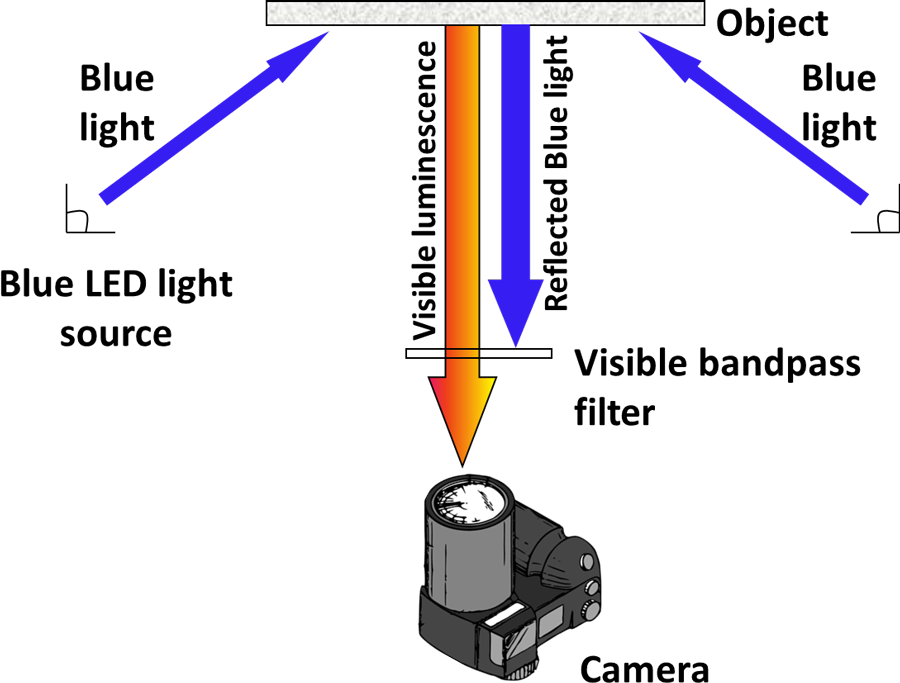

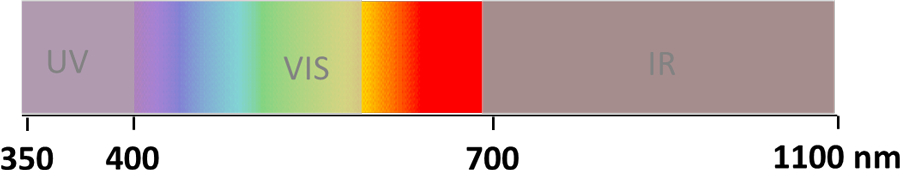

In contrast to methods, which have recently been applied to the study of portraits8 and that require specialized equipment, the procedures described here are based on readily accessible, inexpensive, broadband methods, which cover large sections within the wavelength range that can be observed using modified commercially available cameras. These devices typically employ silicon-based sensors and glass lenses, resulting in an available wavelength range for image acquisition between 350 and 1100 nanometers—that is, from the ultraviolet into the near infrared. The object is illuminated by two radiation sources symmetrically positioned at approximately 45 degrees with respect to the focal axis of the modified camera and at about the same height. The incoming radiation travels toward, and interacts with, the object. Following this interaction, the outgoing radiation travels from the object to the camera. A filter, or a combination of filters, is placed in front of the camera lens in order to select the wavelength range of interest. The experimental setup and the combinations of radiation sources and filter(s) used at the BM for each MSI technique are summarized in figures 6.1 and 6.2. The images are divided into two categories: reflected images and luminescence images.

Reflected images are defined as images in which the wavelength range of the incoming radiation and that of the outgoing radiation are the same (see fig. 6.1). They include:

a) Visible (VIS) images, which correspond to standard photography and record the reflected light in the visible region (400–700 nm) when the object is illuminated with visible light.

b) images, which record the reflected radiation in the infrared region (700–1100 nm) under infrared illumination. By combining components of the VIS and the IRR images, images are produced. As certain colorants can yield a characteristic appearance in false color, these IRRFC images can often be used for their tentative identification.9

c) images, which record the reflected radiation in the ultraviolet region (200–400 nm, depending on the camera lens used) when an object is illuminated with ultraviolet radiation. Components of the VIS and the UVR images can also be combined to produce images.10

d) images, which record reflectance images taken in two different bands or wavelength ranges—in this case, the red region of the visible and the near-infrared region—and subtracts them to give a map of the reflectance of one particular colorant: .11

| MSI Technique and Experimental Setup | Radiation Sources | Filter(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a. VIS |

| 2 x Classic Elinchrom 500 Xenon flashlights, each equipped with a softbox (diffuser) | IDAS-UIBAR interference UV-IR blocking bandpass filter (c. 380–700 nm) |

| b. IRR |

| 2 x Classic Elinchrom 500 Xenon flashlights, each equipped with a softbox (diffuser) | Schott RG830 cut-on filter (50% transmittance at c. 830 nm) |

| c. UVR |

| 2 x Wood’s radiation sources (365 nm) filtered with a Schott DUG11X interference bandpass filter (280–400 nm) | Schott DUG11X interference bandpass filter (280–400 nm) |

| d. MBR |

| 2 x Classic Elinchrom 500 Xenon flashlights, each equipped with a softbox (diffuser) | MidOpt BP 660 dark red bandpass filter (c. 640–680nm) then MidOpt BP735 infrared bandpass filter (715–780nm) |

| MSI Technique and Experimental Setup | Radiation Sources | Filter(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a. VIS |

| 2 x Classic Elinchrom 500 Xenon flashlights, each equipped with a softbox (diffuser) | IDAS-UIBAR interference UV-IR blocking bandpass filter (c. 380–700 nm) |

| b. IRR |

| 2 x Classic Elinchrom 500 Xenon flashlights, each equipped with a softbox (diffuser) | Schott RG830 cut-on filter (50% transmittance at c. 830 nm) |

| c. UVR |

| 2 x Wood’s radiation sources (365 nm) filtered with a Schott DUG11X interference bandpass filter (280–400 nm) | Schott DUG11X interference bandpass filter (280–400 nm) |

| d. MBR |

| 2 x Classic Elinchrom 500 Xenon flashlights, each equipped with a softbox (diffuser) | MidOpt BP 660 dark red bandpass filter (c. 640–680nm) then MidOpt BP735 infrared bandpass filter (715–780nm) |

Luminescence images are defined as images in which the wavelength range of the incoming radiation and that of the outgoing radiation differ (see fig. 6.2). They include:

e) images, which record the emission of light in the visible region (400–700 nm) when the object is illuminated with ultraviolet radiation. UVL images are used to investigate the distribution of luminescent materials—for example, organic binders and colorants, such as —as well as varnishes, coatings, and adhesives.

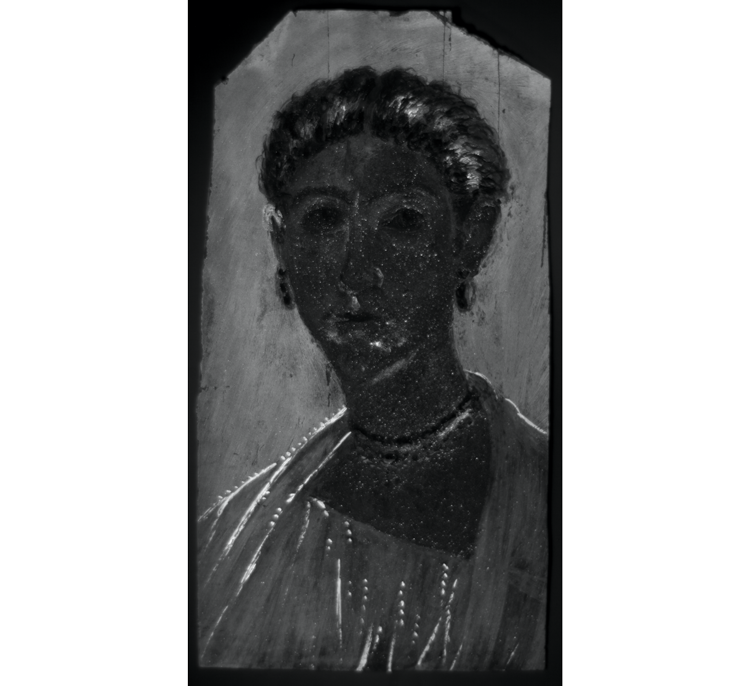

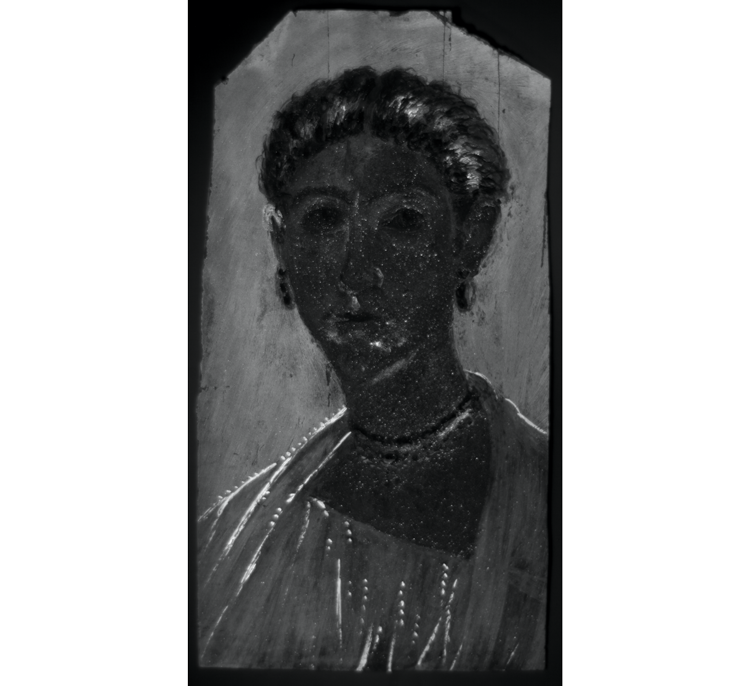

f) images, which record the emission of radiation (luminescence) in the infrared region (700–1100 nm) when the object is illuminated with visible light. Very few materials display this property,12 and in this context the only candidate is the pigment known as , which appears bright white in VIL images.

g) images record the emission of light in a portion of the visible region (here, 500–700 nm) when the object is illuminated with visible light (here, blue light, 400–500 nm). A VIVL image is in many ways analogous to a UVL image, but the emission range makes it particularly useful in characterizing the spatial distribution of yellow and red lake pigments, such as . VIVL images can be processed to produce maps of the distribution of these pigments, in either color or grayscale.13

| MSI Technique and Experimental Setup | Radiation Sources | Filter(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| e. UVL |

| 2 x Wood’s radiation sources (365 nm) filtered with a Schott DUG11X interference bandpass filter (280–400 nm) | Schott KV418 cut-on filter (50% transmission at c. 418 nm) + IDAS-UIBAR bandpass filter (c. 380–700 nm) |

| f. VIL |

| 2 x high power LED (red, green, and blue) light sources (Eurolite LED PAR56 RGB spots 20W, 151 LEDs, beam angle 21°) | Schott RG830 cut-on filter (50% transmittance at c. 830 nm) |

| g. VIVL |

| 2 x high power LED (red, green, and blue) light sources (Eurolite LED PAR56 RGB spots 20W, 151 LEDs, beam angle 21°). Blue LEDs | IDAS-UIBAR bandpass filter (400–700 nm) + Tiffen Orange 21 filter (50% transmission at 550 nm) |

| MSI Technique and Experimental Setup | Radiation Sources | Filter(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| e. UVL |

| 2 x Wood’s radiation sources (365 nm) filtered with a Schott DUG11X interference bandpass filter (280–400 nm) | Schott KV418 cut-on filter (50% transmission at c. 418 nm) + IDAS-UIBAR bandpass filter (c. 380–700 nm) |

| f. VIL |

| 2 x high power LED (red, green, and blue) light sources (Eurolite LED PAR56 RGB spots 20W, 151 LEDs, beam angle 21°) | Schott RG830 cut-on filter (50% transmittance at c. 830 nm) |

| g. VIVL |

| 2 x high power LED (red, green, and blue) light sources (Eurolite LED PAR56 RGB spots 20W, 151 LEDs, beam angle 21°). Blue LEDs | IDAS-UIBAR bandpass filter (400–700 nm) + Tiffen Orange 21 filter (50% transmission at 550 nm) |

MSI techniques have increasingly become a part of the range of examination and analytical methodologies that conservation professionals have at their disposal, yet there are certain issues to be aware of with MSI techniques. In general, without standardization, the images obtained from these methods very much depend on the individual users and the setup employed, making cross-comparison between different institutions and researchers very difficult and decreasing the value of these data sets as documentation aids. This need for standardization was one that was identified by CHARISMA,14 a recent European project, which strived to establish standards in areas that have traditionally lacked guidelines, such as MSI. Research was undertaken to develop new optimized methodologies for both the acquisition and the processing of images, to improve their reproducibility and comparability both within and between institutions. The outcomes of this research were distilled into a set of completely open-access user resources downloadable from the BM website.15

However, standardization does not end with producing these images—their interpretation also requires guidelines and a methodical approach to recording the information observed in order to derive useful data and objective comparisons. Workflows are a practical solution, as they provide a framework for systematically analyzing data and are already a familiar approach to conservation professionals who acquire and process images.16 A workflow was thus devised, which could be followed for each portrait, allowing certain characteristic physical properties and their spatial distribution to be recorded and interpreted in an informed and impartial manner across the collection.

Workflows for MSI Interpretation

As a first approach, pigments were selected that are considered typical of the palette used in these portraits; the distinctive properties of these pigments—such as particular reflectance or luminescence in particular regions—can be used for their preliminary identification. Other materials related to conservation treatments and past restoration interventions, particularly those using modern materials, could also be addressed in this manner; however, it was initially decided to simplify the approach to this class of materials. The pigments selected were Egyptian blue, pink lake, , ochres, , indigo, and copper-based greens.

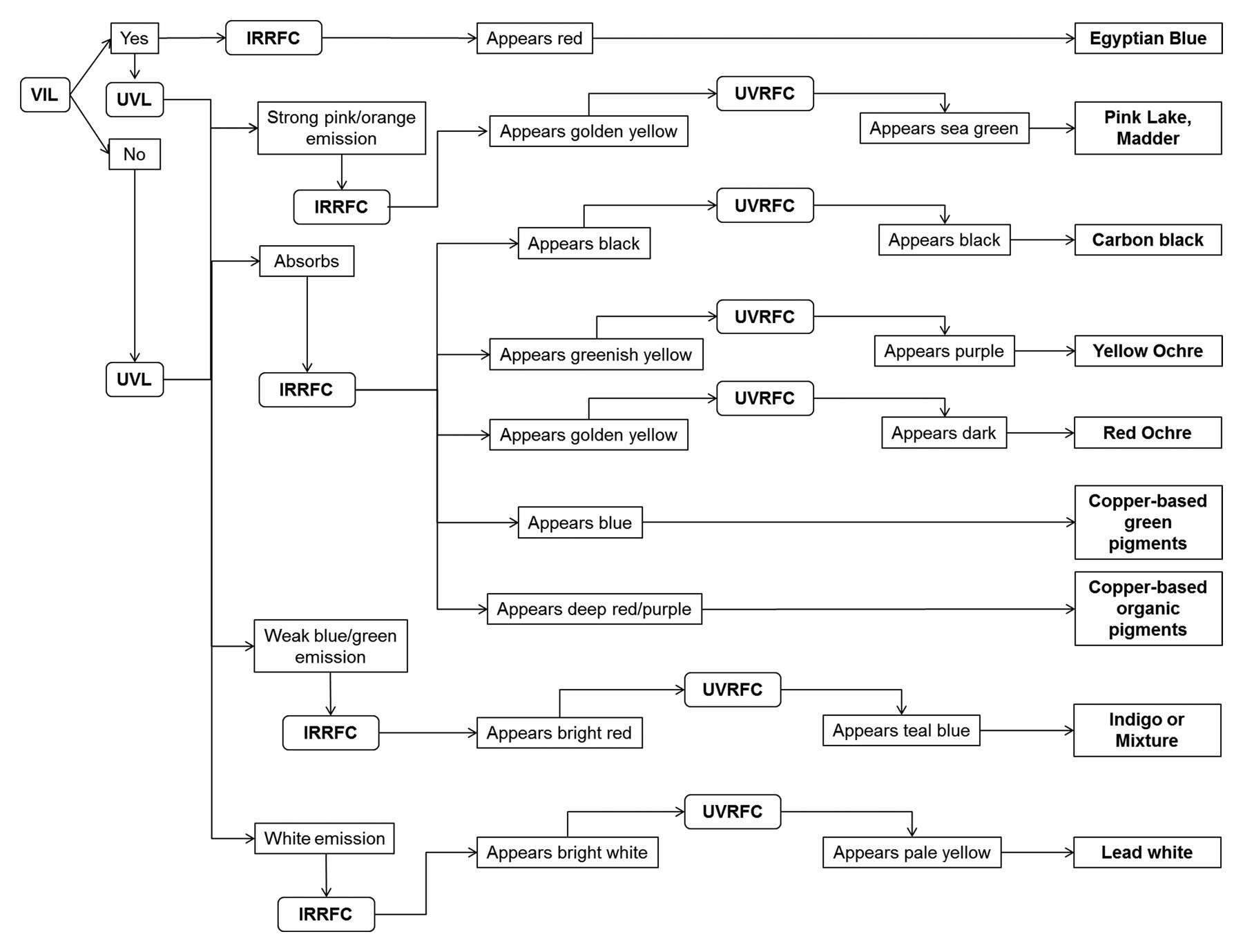

In general, it was evident that the most useful approach involved compiling a combination of the photophysical properties observed into a signature behavior for each of the materials in question; this methodology was synthesized into a basic initial workflow, shown in figure 6.3. Although not a comprehensive list of every pigment known to occur in the production of these portraits, this inventory does represent a key subset, and the workflow was invaluable in assessing the presence or absence of these significant pigments. Their distribution and use were then documented according to a set of criteria optimized for each pigment. The results were tabulated and expressed as bar charts showing the key trends observed from portraits in the BM collection and the number of portraits that exhibit them. These trends, and the representative portraits that display them, are discussed in more detail below.

Figure 6.3

Figure 6.3Egyptian Blue

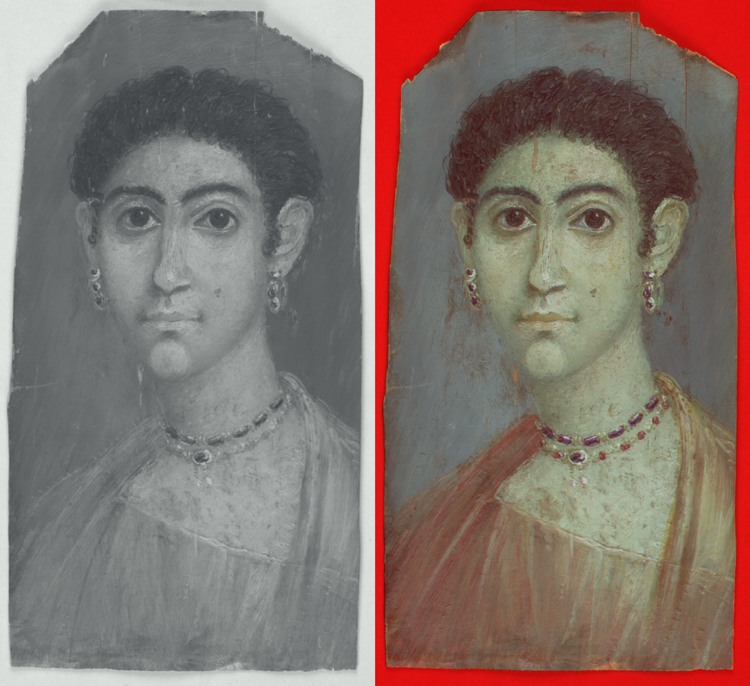

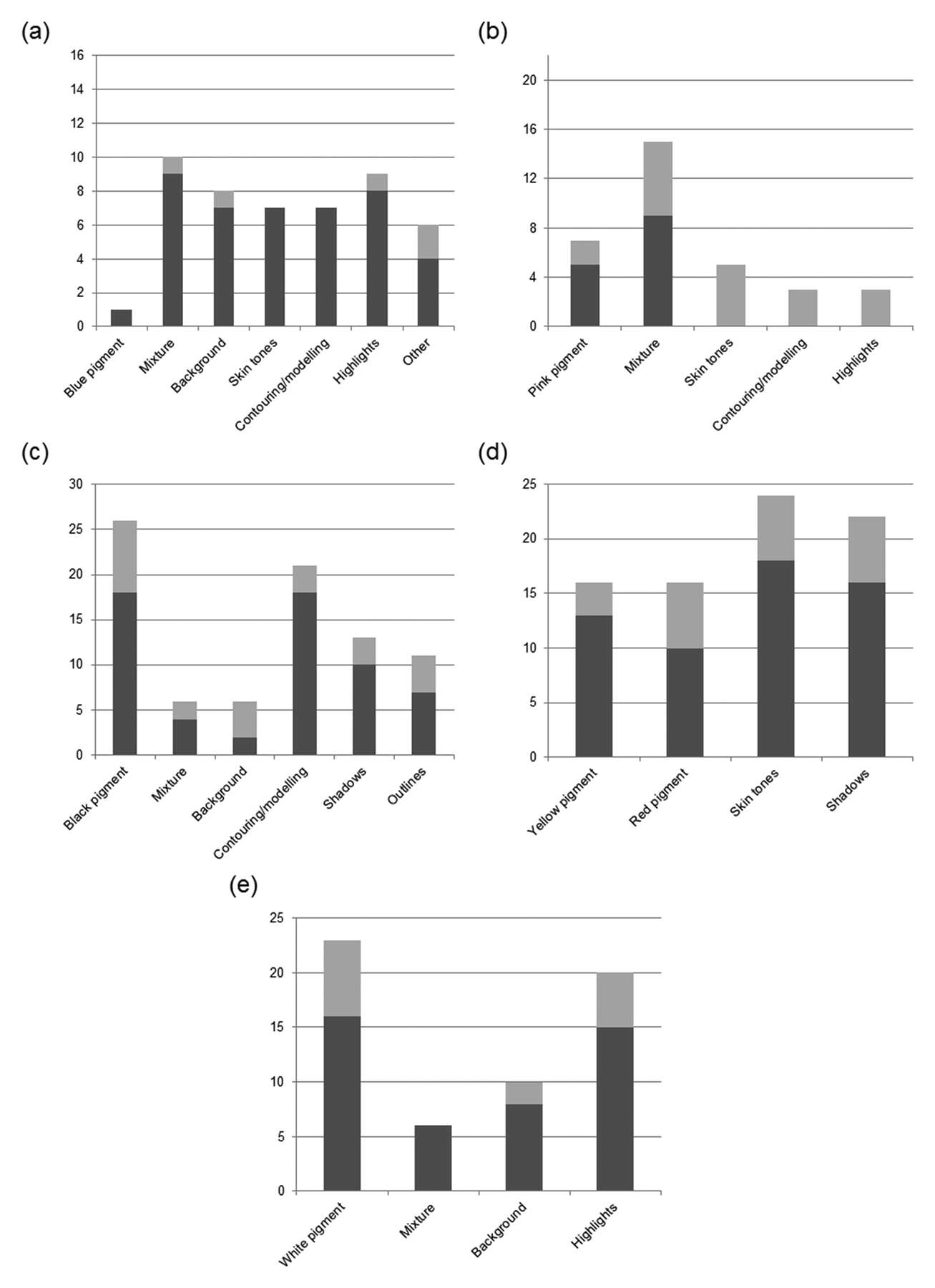

As discussed, the pigment Egyptian blue produces signature visible-induced luminescence in the infrared region, but it also demonstrates characteristic behavior in IRRFC images (see fig. 6.3) due to its high reflectance17 beyond the visible. Egyptian blue was identified in sixteen of the portraits imaged, with a fairly even spread chronologically and in its use for both male and female portraits. In addition, the pigment appears to be more prevalent in encaustic portraits, with only three of the tempera and one of the encaustic and tempera portraits containing it; however, what soon becomes evident from looking at the VIL images themselves is the diversity of usage of the pigment within these portraits. Use of Egyptian blue ranges from its presence in mixtures—for the backgrounds and in the depiction of garments and gemstones—to its use in a variety of subtle and highly painterly ways of modeling, contouring, and highlighting different aspects of the compositions. To systemically document this wide-ranging use of Egyptian blue pigment, a set of criteria was employed that considered not only how, but also where, it is being used within the portraits; this allowed key trends to be documented, as summarized in figure 6.4a, which plots the number of portraits displaying each identified use of the pigment.

Figure 6.4

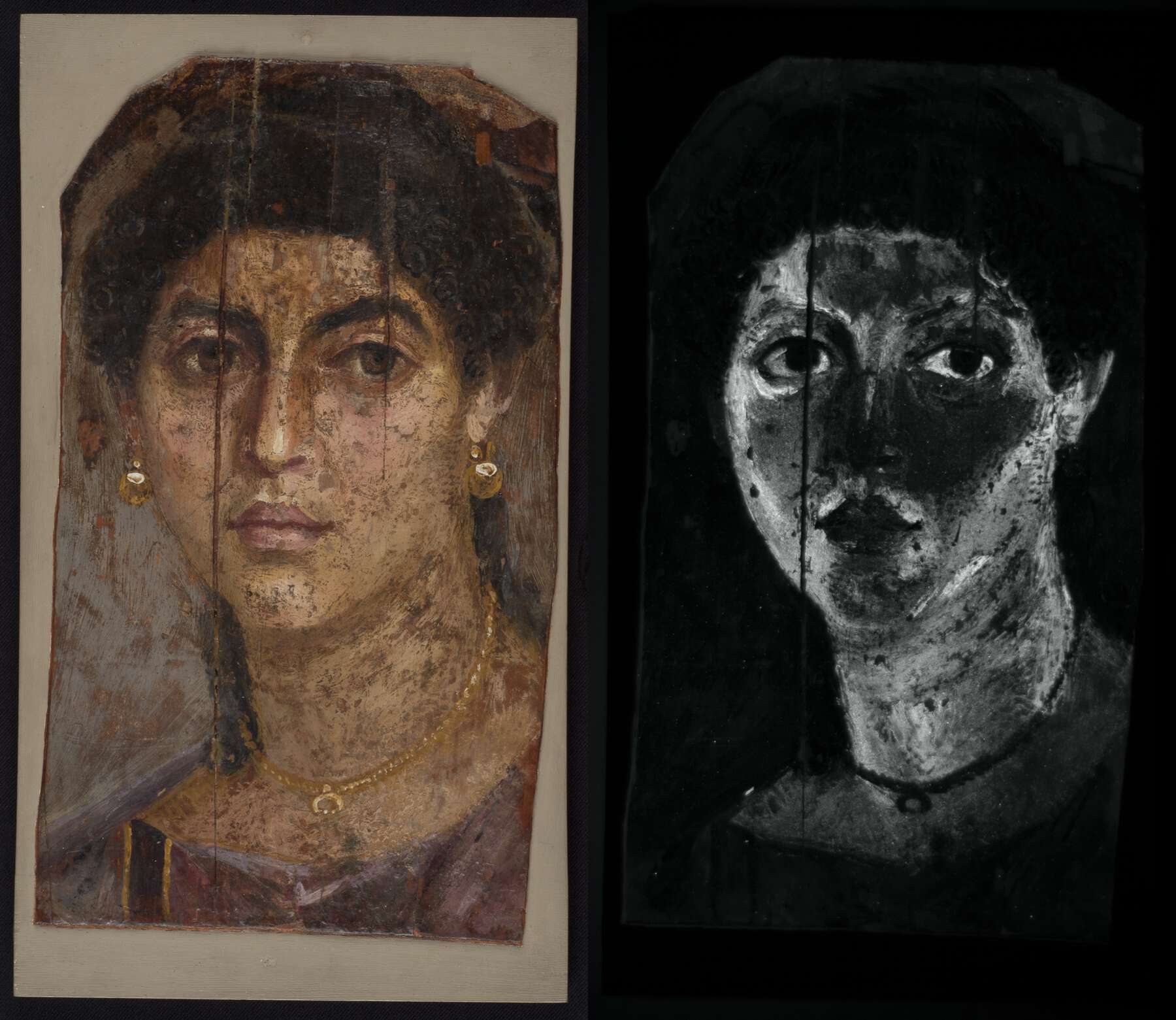

Figure 6.4From this analysis, it was possible to deduce that within the BM portrait collection, Egyptian blue is only sparingly employed as a pure blue pigment and, in fact, can only be found in one portrait (see fig. 6.4a), in the garment of the so-called Portrait of a Lady, shown in figure 6.5a. In this same portrait, Egyptian blue was also used as a component of a mixture with yellow to depict the green jewels in the necklace and earrings. Mixtures were indeed found to be the most popular use of the pigment, identified in ten portraits (see fig. 6.4a). Mixtures with white were observed in the whites of the eyes and in areas of the drapery (as in fig. 6.5a) in several portraits, whereas mixtures with pink lake were less prevalent and observed in only two portraits: in the garment of a female portrait (fig. 6.5b) and in the of a male portrait (EA74832, not shown).

Extensive use of Egyptian blue was also detected mixed into skin tones (see fig. 6.4a), as a means to create both light and shade (figs. 6.5c-1 and 6.5c-2). Additionally, widespread use of the pigment in mixtures was noted, to create highlights (see fig. 6.4a), in the treatment of garments, and to suggest volume and dimensionality (fig. 6.5d). Furthermore, Egyptian blue was found to have been used in a mixture in the colored backgrounds in eight of the portraits imaged (see fig. 6.4a).

Figure 6.5a

Figure 6.5a Figure 6.5b

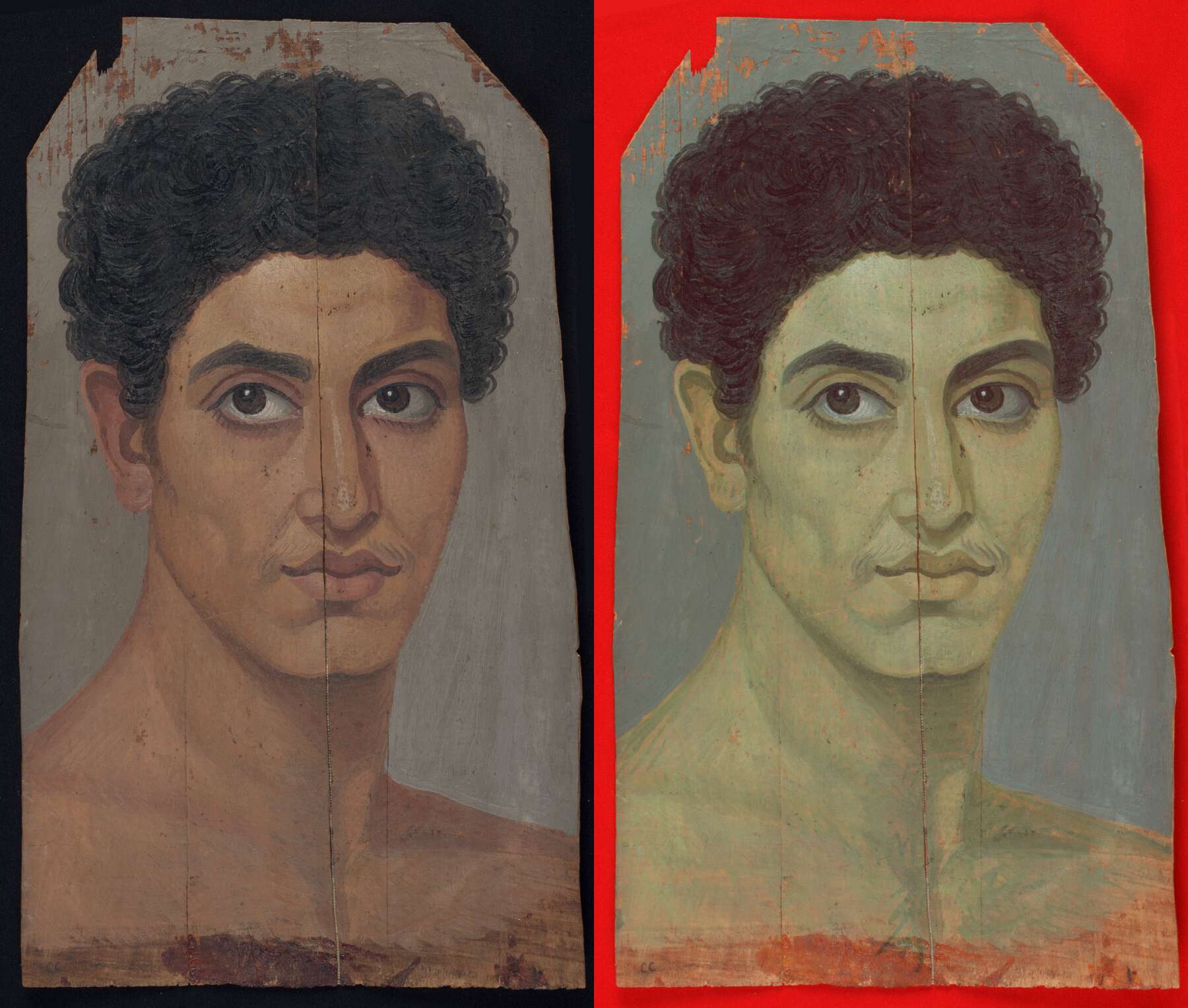

Figure 6.5b Figure 6.5c-1

Figure 6.5c-1 Figure 6.5c-2

Figure 6.5c-2 Figure 6.5d

Figure 6.5dPink Lake

Pink lake pigments, of which madder lake is the most emissive,18 produce distinctive pink/orange luminescence under ultraviolet radiation. In addition, pink lakes such as madder appear golden yellow in IRRFC and sea green in UVRFC images (see fig. 6.3). This characteristic behavior was noted in twenty-two of the portraits imaged, again with an evenly spread chronology of use. Pink lake was detected more often in female portraits, and it is present in fourteen of the encaustic and all but one of the tempera portraits.

To document the distribution and use of the pink lake pigment, an approach similar to that described for Egyptian blue was employed; the results are summarized in figure 6.4b. This examination indicated that the major use of pink lake as a pink pigment (in eight portraits; see fig. 6.4b) is in the garments and lips, particularly in female portraits, as exemplified by that shown in figure 6.6a.

Mixtures of pink lake with various pigments constitute its most prevalent use (in fifteen portraits; see fig. 6.4b). In particular, it was used to modify the hue of garments to a dark red, as seen in the portrait in figure 6.6b, or to create purple shades in the clavi of several male portraits that evoke the Tyrian purple–dyed clavi worn by high-status Roman men.

Additionally, pink lake is observed in mixtures to both model and highlight skin tones (see fig. 6.4b), as seen in the portraits in figures 6.6c-1 and 6.6c-2. This practice was not as widespread in male portraits, except for the portrait of a youth shown in figure 6.6c; perhaps here it was employed to convey an age-appropriate freshness to his complexion. However, the use of mixtures to highlight certain areas (see fig. 6.4b), as in the portrait in figure 6.6d, was observed in a few male and female portraits. Another interesting use of the pigment is in the depiction of jewels (see below).

Figure 6.6a

Figure 6.6a Figure 6.6b

Figure 6.6b Figure 6.6c-1

Figure 6.6c-1 Figure 6.6c-2

Figure 6.6c-2 Figure 6.6d

Figure 6.6dCarbon Black

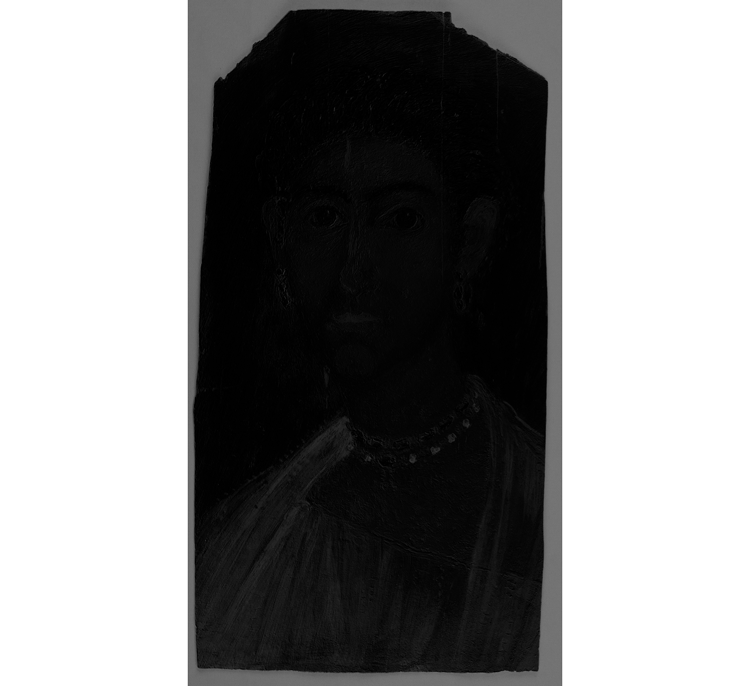

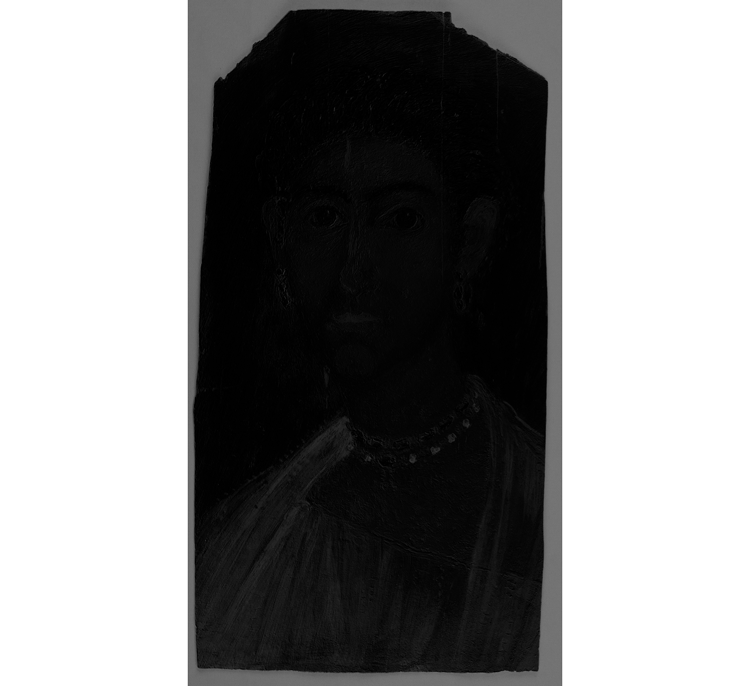

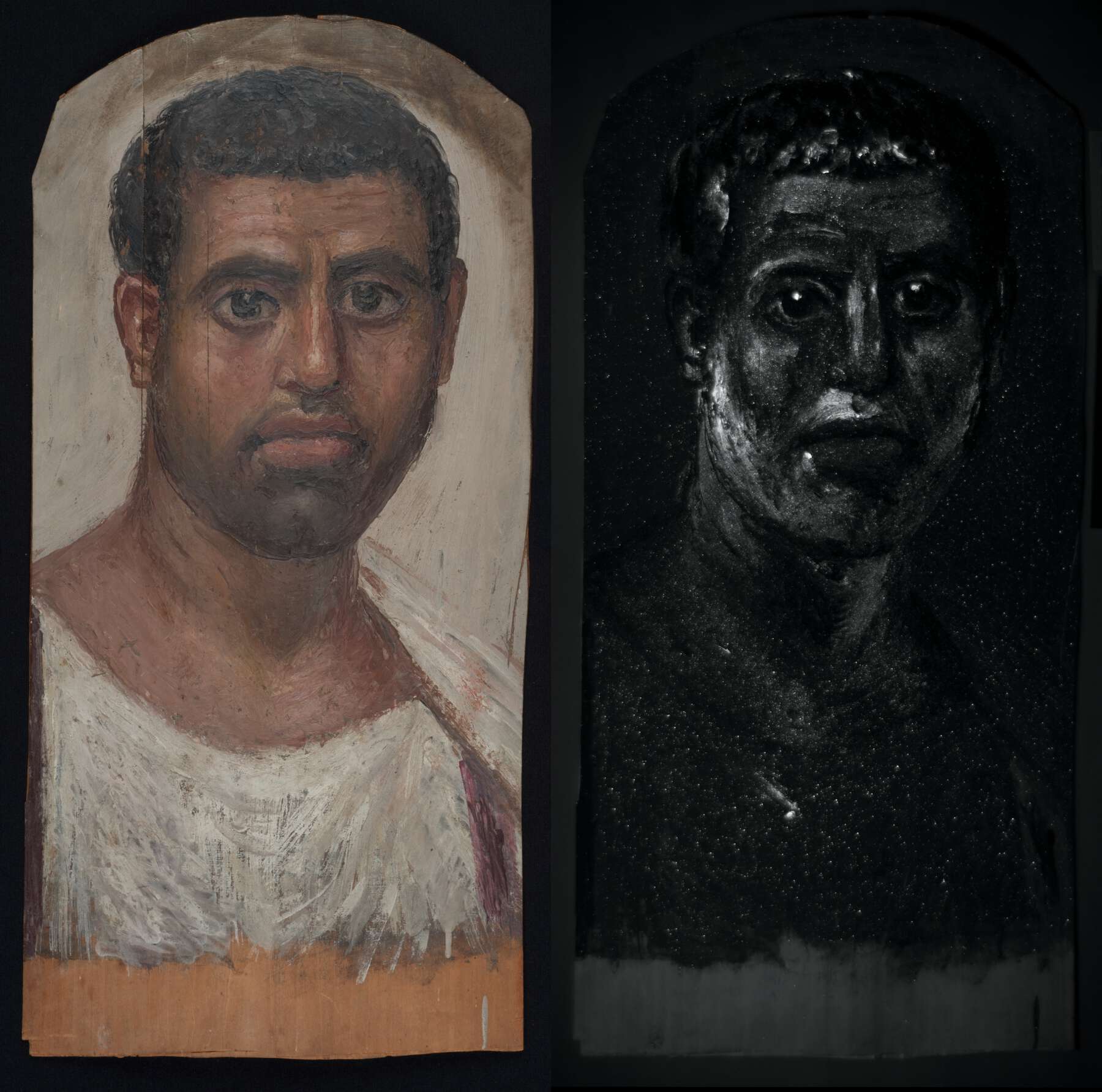

Found on all the portraits imaged, carbon black was indeed the most ubiquitous of the pigments. As a result of its high absorbance across the range investigated, the pigment appears dark in all of the images recorded and, characteristically, remains dark in false color images (see fig. 6.3). This is particularly evident in the IRRFC images (figs. 6.7a and 6.7b) and is in contrast to areas that appear black in VIS images but are red (IR transparent) in IRRFC images.

Investigation of the distribution and use of carbon black showed that in all twenty-six cases, it was used as a pure black pigment (see fig. 6.4c) to depict the hair, eyes (particularly pupils), and eyebrows, as shown by the portrait in figure 6.7a, and, where present, facial hair and black clavi. An additional function, observed in eleven cases (see fig. 6.4c), was to outline facial features such as eyes and eyelids, pupils, irises, and noses. Jewelry was also often observed to be outlined in this manner.

Mixtures of carbon black with other pigments were noted (see fig. 6.4c): with white to produce a gray shade used to contour and model skin tones, adding definition to the face, neck, and jawline. Warmer shades were used to create shadows, particularly under the eyes, nose, and lips. These attenuate the appearance of the pigment in IRRFC to shades of gray, as in the portrait shown in figure 6.7b, while remaining quite dark (absorbing) in the UVL images.

In other cases, such as when carbon black and pink lake have been mixed to produce darker red tones in the garments, carbon black’s presence is manifested by a darkening of pink lake’s characteristic golden yellow and sea-green hues in IRRFC and UVRFC images, respectively, but the intensity of the luminescence from the lake is hardly attenuated.

In certain instances, areas appeared very dark or visibly black but did not remain black in the IRRFC images, as in the portrait in figure 6.7c. This behavior allowed the presence of carbon black to be distinguished from visually similar materials that are not carbon based, such as bituminous materials or organic colorants such as indigo (see below), which are infrared transparent and thus appear red in IRRFC.

Figure 6.7a

Figure 6.7a Figure 6.7b

Figure 6.7b Figure 6.7c

Figure 6.7cOchres

Twenty-five of the portraits imaged showed evidence for the presence of ochres, either as pure pigments or mixtures, establishing this as the second most commonly used class of pigments. Sixteen of the twenty-five showed use of as a yellow pigment (see fig. 6.4d), mostly to evoke the color of gold in the jewelry, clavi, and other adornments, especially on female portraits, such as that shown in figure 6.8a. Yellow ochre was identified by its distinctive set of characteristics, appearing very absorbing in UVL, dark greenish yellow in IRRFC, and purple in UVRFC images (see fig. 6.3). In three portraits, it was also employed as the bole layer for gilded areas.

Although also highly absorbing in UVL images, appears dark golden yellow in IRRFC and very dark in UVRFC images (see fig. 6.3). These characteristics allowed the identification of its use as a dark red pigment in sixteen portraits (see fig. 6.4d), most notably in the outlining and definition of facial features in both male and female portraits, but also in garments and lips, as in the portrait shown in figure 6.8b. In one case, it was also observed as a red bole beneath .

The use of the red ochre in various shades for the depiction of skin tones and to produce shadows around the eyes, beneath the nose, under the chin, and along the neck and jawline was also noted by the attenuation to paler shades of (greenish) yellow observed in the IRRFC images (as in figs. 6.7a and 6.7b). The UVL images remain highly absorbing, as noted from the faces of the portraits in figures 6.6a, 6.6b, and 6.6d.

In six of the portraits, evidence for the use of yellow ochre in mixtures, via an attenuation of the purple tone observed in the UVRFC images, was also observed in the skin tones (fig. 6.8c).

Figure 6.8a

Figure 6.8a Figure 6.8b

Figure 6.8b Figure 6.8c

Figure 6.8cLead White

Twenty-three portraits likely contain lead white present as a pure white pigment (see fig. 6.4e), as identified from its characteristic white emission in UVL images. The pigment is also highly reflective in the entire range, appearing white in IRRFC and pale yellow in UVRFC (see fig. 6.3). These observations are most discernible in white areas such as the garments (see figs. 6.7b and 6.8c) and eyes (see fig. 6.7a).

However, almost as important as the use of lead white as a white pigment, and observed in twenty portraits (see fig. 6.4e), is its use, often in mixtures, to represent how light naturally falls on facial features; lead white was similarly employed to suggest highly reflective surfaces, such as gold or gemstones, via the creation of highlights.

Further uses were noted: in mixtures with pink lake pigments; used as a counterfoil to mixtures of pink lake and black; to create volume, depth, and dimension in the depiction of garments; and in the backgrounds of ten portraits (see fig. 6.4e), particularly to produce a light gray, often in mixtures with Egyptian blue and/or carbon black. In these cases, the effect of the pigment on the false-color images is to lighten the hue observed.

Indigo

The presence of indigo, even in a mixture, is easily identified from its distinctive photophysical characteristics, appearing dark in VIL images, weakly emitting under ultraviolet irradiation, bright red in IRRFC, and teal blue in UVRFC images (see fig. 6.3). Only six portraits displayed these properties, revealing use of indigo both as a pure pigment and in mixtures, and in both encaustic and tempera portraits.

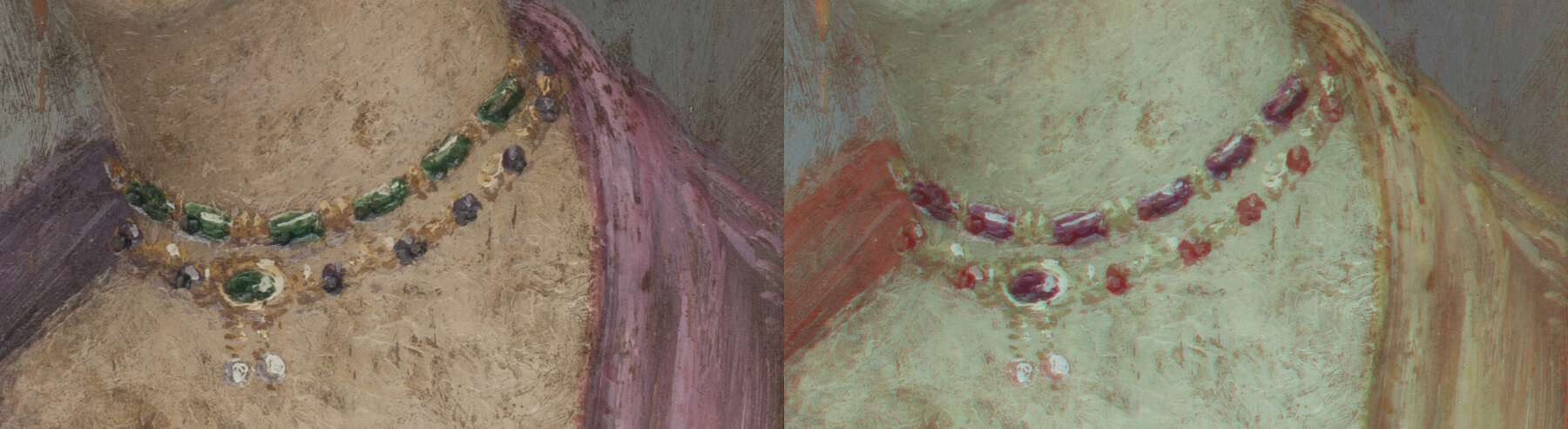

The clearest use of indigo as a blue pigment is observed in the portrait shown in figure 6.9a, where the blue necklace beads have been painted with it. Two uses of indigo in mixtures to create new hues were also observed: mixed with yellow, to depict the green jewels in the necklace of the portrait shown in figure 6.9b, and with pink lake in different proportions, to produce the purple-toned garment and deep red jewels observed in the portrait in figure 6.9c. In IRRFC images the appearance of mixtures, relative to that of the pure pigments, is modified according to the proportion of each pigment. The presence of a small amount of indigo thus attenuates the golden yellow appearance of pink lake areas to a more orange hue, as in the garment in figure 6.9c; whereas, with a larger proportion of indigo, the typical appearance of the latter is more prevalent and the presence of lake can be difficult to discern.

In this regard, using a combination of MBR and VIVL images (fig. 6.9d) can often be valuable to identify such mixtures, as each image isolates the signals from the respective pigments, thus allowing them to be compared more easily. The coexistence of these pigments—in this case, in the garment and the necklace beads—can then be more clearly visualized. Figure 6.9a

Figure 6.9a Figure 6.9b

Figure 6.9b Figure 6.9c

Figure 6.9c Figure 6.9d

Figure 6.9d

Copper-Based Greens

Seven distinctive uses of green were observed in the portraits imaged; all uses were to depict gemstones in jewelry, and four of the instances were found to be copper-based greens: one inorganic pigment (such as or Egyptian green) and three organometallic pigments (copper fatty acid carboxylates). Both classes appear dark in the VIL and UVL images and are particularly absorbing in the latter. The main difference between inorganic and organometallic copper-based green pigments is the variation in their infrared transparency and, as a result, how they appear in the IRRFC images (see fig. 6.3). Thus, whereas mineral pigments are not very transparent in the infrared region19 and appear blue (fig. 6.10a), the organometallic pigments have much higher infrared transparency and thus appear a deep red (fig. 6.10b). This behavior is also distinctive from that of other greens, such as iron-based silicate pigments (), which usually appear absorbing under ultraviolet irradiation and a dull green in IRRFC images (fig. 6.10c), or mixtures of yellow and indigo or Egyptian blue, which also have particular characteristics, as previously described. Interestingly, within this fairly small sample of portraits, all of these available possibilities for green pigments discussed were represented, but the copper-based organometallic greens were observed only in encaustic portraits.

Figure 6.10a

Figure 6.10a Figure 6.10b

Figure 6.10b Figure 6.10c

Figure 6.10cConclusions

This work has described the application of current MSI methods in use at the BM to the study of its collection of Greco-Roman funerary portraits from Egypt. As with all noninvasive methods, the corroboration of the observations made from these investigations with other findings is important and will be considered in future work, but the results confirm that these technically accessible, relatively low-cost methods are a powerful tool for surveying such collections, providing a holistic overview that is invaluable in gauging the extent of distribution of particular materials and their mixtures. This more representative view is not always achievable with point analyses and is particularly significant when sampling is not possible. In addition, the approach can also aid decisions in terms of more focused and targeted invasive sampling, when this is permissible, resulting in less damage to these fragile objects.

In particular, this work has highlighted the importance of standardization—not only in the acquisition and processing of images but also in their interpretation—so as to provide a framework for systematically recording information. Observations resulting from this approach constitute an objective record of the presence, distribution, and use of pigments present in these portraits. It is hoped that through the contribution of this work to the APPEAR project, cross-comparisons with other collections will be stimulated, which will allow meaningful insights that can be used to further explore the painting practices of funerary portraiture of the period.

Notes

- . ↩

- ; . ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- Four of the portraits were not accessible, as they are on long-term loan to various institutions in the United Kingdom. ↩

- ; . ↩

- , 4; . ↩

- , 4; . ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- Cultural Heritage Advanced Research Infrastructures: Synergy for a Multidisciplinary Approach to Conservation/Restoration, funded under FP7-Infrastructures (grant agreement 228330). ↩

- . ↩

- . ↩

- , 1497. ↩

- . ↩

- , 1496. ↩