8. Invisible Brushstrokes Revealed: Technical Imaging and Research of Romano-Egyptian Mummy Portraits

Little is known about the techniques or materials employed for underdrawings in Romano-Egyptian mummy portraits. Preliminary sketches are not typically observed on painted funerary portraits; however, during recent technical investigations on three distinct mummy portraits at three different institutions, conservators using technical imaging revealed previously undetected brushstrokes. Under the auspices of the APPEAR project, the Penn Museum (Penn), J. Paul Getty Museum (Getty), and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) independently discovered formerly unobserved brushstrokes by using imaging on certain mummy portraits in their collections. The “invisible brushstrokes,” or fluorescence,1 are not visible to the naked eye, but they are present on three very distinct portraits ranging in temporal periods (AD 100–250), painting techniques (e.g., versus ), and substrates (e.g., wooden versus textile). Although all the portraits depict young men, these invisible brushstrokes appear to have been employed for different stylistic effects. Uniting these observations is the fact that the brushstrokes were undetected until the portraits were imaged under a narrow band of visible light (535–555 nm).

The principal application for VIVL imaging in the conservation field has been to visualize fluorescent (or other materials) on painted surfaces. Materials that exhibit luminescence (emitted radiation) can be excited by a wide range of wavelengths, but optimum excitation occurs within a narrow range of wavelengths. For this paper, various methods of observing VIVL on mummy portraits were compared, and we found that detecting the invisible brushstrokes required specific setups and access to specialized equipment. Because VIVL fluorescence can be weak and easily quenched, a careful evaluation of materials must occur before interpreting VIVL imaging results.

The collaborative nature of the APPEAR initiative facilitated connections and exchange of expertise across disciplines, which was essential for this paper. Without this framework, the independent discoveries of these invisible brushstrokes could have been attributed to specific mummy portraits rather than interpreted collectively as a new phenomenon. A goal of this paper is to encourage institutions to continue to undertake basic research on mummy portraits in their collections and share findings. The discovery of the invisible brushstrokes at the Penn, Getty, and MFA happened within the research priorities of each institution, and we are indebted to colleagues in conservation science, imaging, and curatorial for their valuable input. The research is ongoing, and this publication strives to present the initial findings.

Imaging and Analysis Background

The VIVL imaging that revealed this phenomenon was possible because each institution had access to a SPEX CrimeScope unit, a tunable radiation source used for forensic applications.2 The wavelength of the emitted light is controlled by filter wheels that enable objects to be examined under lighting conditions ranging from ultraviolet (UV) to infrared (IR). When each portrait was imaged specifically with the CrimeScope at 535 nanometers and 555 nanometers, previously unobserved brushstrokes became visible. The brushstrokes exhibited a response similar to that of , which has a known fluorescence excitation maximum of approximately 550 nanometers and an emission maximum of approximately 600 nanometers.3 The unexpected detection of these invisible brushstrokes prompted further questions about the artists’ materials, intentions, and working techniques. Madder lake was identified on other areas of the paintings, such as the purple on the MFA portrait and the purple on the Getty .4 The similar behavior of the areas of confirmed madder and the invisible brushstrokes, when imaged with the CrimeScope, prompted the hypothesis that the fluorescent brushstrokes could be a madder-based material (e.g., an organic lake pigment.) The facts that the brushstrokes could not be detected through the standard diagnostic methods using ultraviolet (UV) radiation (300–400 nm), are not readily evident on the surface in visible light, and cannot be identified through nondestructive surface analyses indicate that they may be present as a mixture or underlayer; however, the extensive sampling needed to confirm this hypothesis was not possible at this time.

To investigate these invisible brushstrokes, conservators, conservation scientists, and imaging specialists carried out thorough examination, imaging, mock-ups, and both nondestructive and destructive technical analysis on the three mummy portraits. Techniques employed included optical microscopy (OM), , , standard , (portable) , , fluorescence excitation-emission matrix spectroscopy (EEM), , , liquid chromatography/mass spectroscopy (LC/MS), and .5 An important goal of this Penn-Getty-MFA collaborative project is to replicate the CrimeScope VIVL images at the narrow bandpass of 535 to 555 nanometers without the use of this expensive and proprietary instrument. The hope is to present a possible imaging alternative, making this type of investigation more accessible to a greater number of institutions. Given that this phenomenon was discovered on three distinct portraits, it is likely that this unexplained fluorescence could be found on additional Romano-Egyptian mummy portraits.

Discovery of the Brushstrokes

The Penn Museum has been actively collecting technical data on three Romano-Egyptian mummy portraits in its collection. The painting pivotal to this research, Portrait of a Young Man (fig. 8.1), depicts a youthful man with dark curly hair, large eyes, and facial hair; he wears a white tunic. Executed on a white background, the painting was painted in encaustic on a wooden panel; based on style, the work has been dated to approximately AD 100. Records indicate that the portrait was discovered in .6 It entered the Penn Museum in 1894, when the portrait was purchased from the collection of Theodore Graf. Initial examination of the panel revealed nothing unexpected;7 however, when the work was imaged with the CrimeScope at specific wavelengths of light (535 nm and 555 nm), cursory brushstrokes outlining the figure became clearly visible (fig. 8.2). The brushstrokes appear to have been executed quickly, perhaps serving to roughly sketch out the composition. The exact location of the lines within the paint stratigraphy, however, could not be confirmed. Given the fluorescence range, a madder-based pigment was suggested early on as a potential material known to have been used on mummy portraits. Figure 8.1

Figure 8.1 Figure 8.2

Figure 8.2

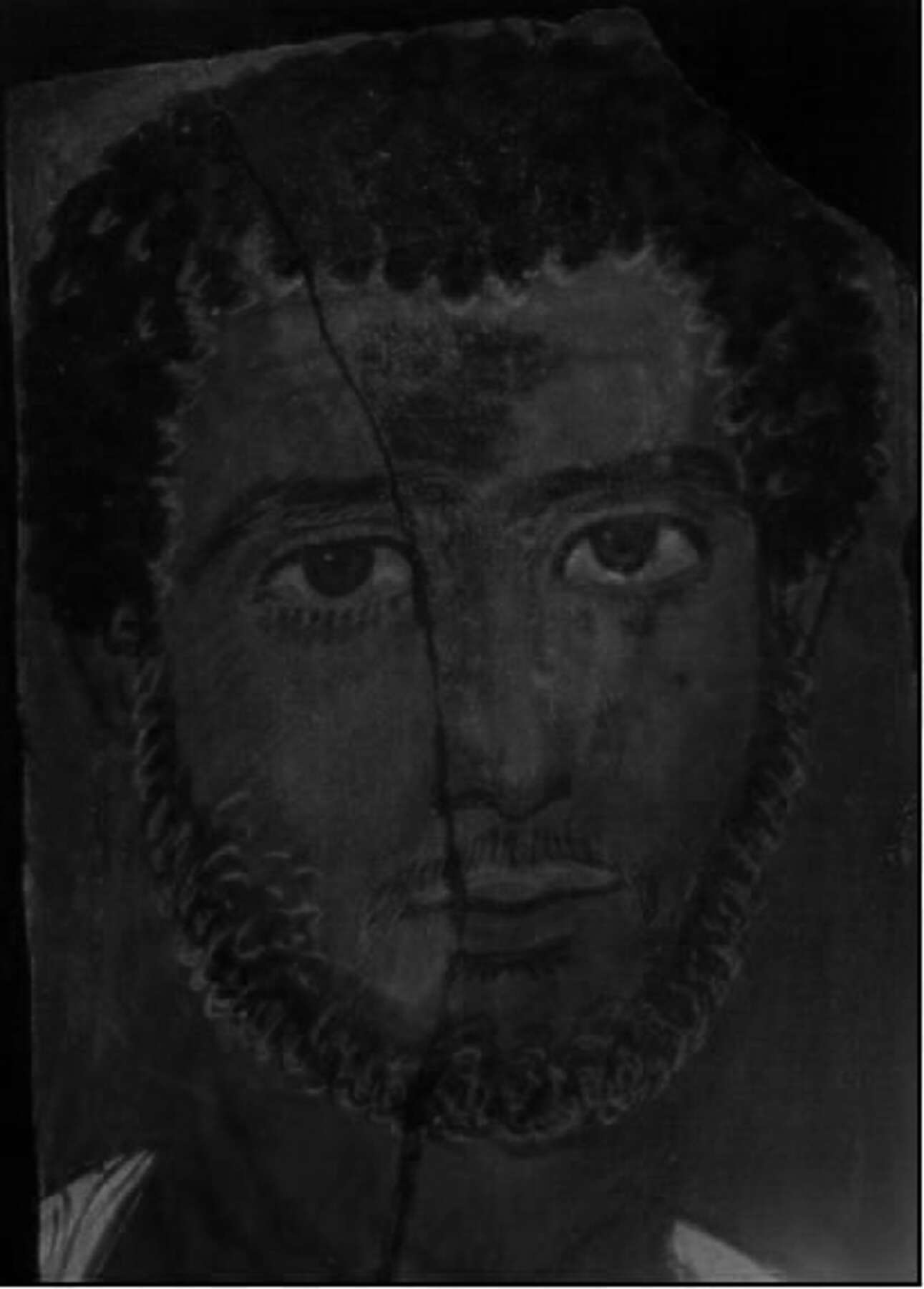

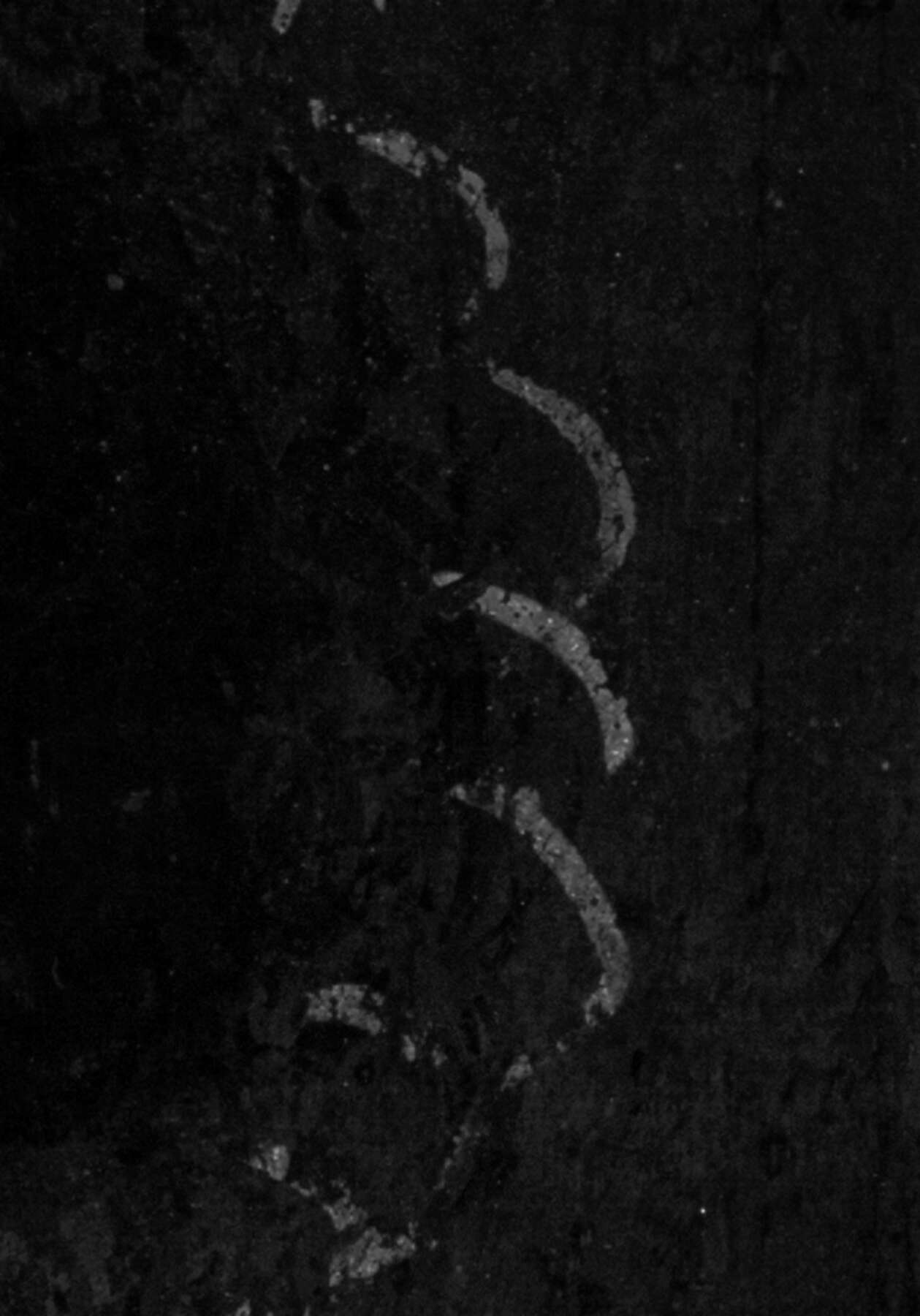

The Getty’s sixteen Romano-Egyptian mummy portraits were also examined and imaged using the CrimeScope.8 Only one portrait revealed an unexpected fluorescence: Mummy Shroud with Painted Portrait of a Boy (fig. 8.3), which shows a dark-haired, large-eyed young boy wearing a white tunic with purple clavi. He has a with green leaves and yellow berries, and a hawk perches on his proper left shoulder. The shroud, painted with tempera on linen, dates to approximately AD 72 to 213.9 Although the exact findspot in Egypt is unknown, the mummy shroud entered the Getty Museum in 1975 as a gift from Lenore Barozzi. Following a systematic approach in the study of the Getty portraits, extensive analysis and imaging were carried out on the shroud.10 Imaging the portrait with the CrimeScope revealed invisible brushstrokes restricted to the area just under the eyes, at the same 535 nanometers and 555 nanometers narrow bandpass (fig. 8.4). The fluorescence was not detected with any other analytical or imaging technique, and FORS analysis identified only (hematite) on the surface. The young boy’s clavi, confirmed to be madder lake,11 exhibited a fluorescence similar to that of the area under the eyes, which suggests that a madder-based pigment could have been used within the stratigraphy of the paint layers. The highly specific use of a pinkish tone under the eyes implies that the artist may have been attempting to create dimension and a fleshlike effect—a sophisticated approach to painting by the ancient artist. Figure 8.3

Figure 8.3 Figure 8.4

Figure 8.4

In 2016 the British Museum hosted the interim APPEAR meeting, where speakers presented their preliminary research. Researchers from both the Penn and Getty discussed their independent findings of these invisible brushstrokes, initiating discussion and establishing research collaborations between museum participants. In subsequent months, the MFA would also discover previously undetected brushstrokes with VIVL imaging, after using the CrimeScope on one of its mummy portraits, and join the partnership.12

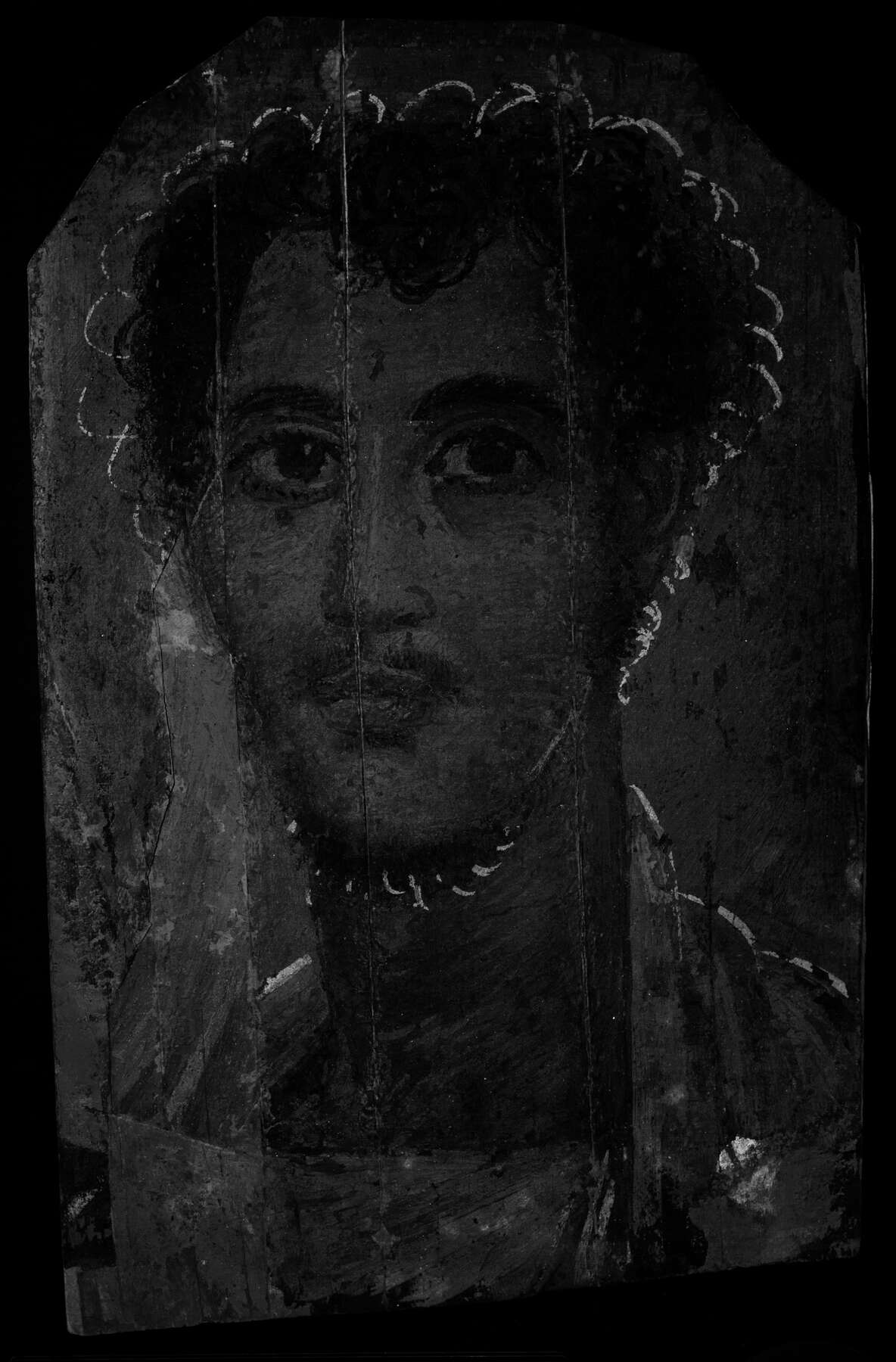

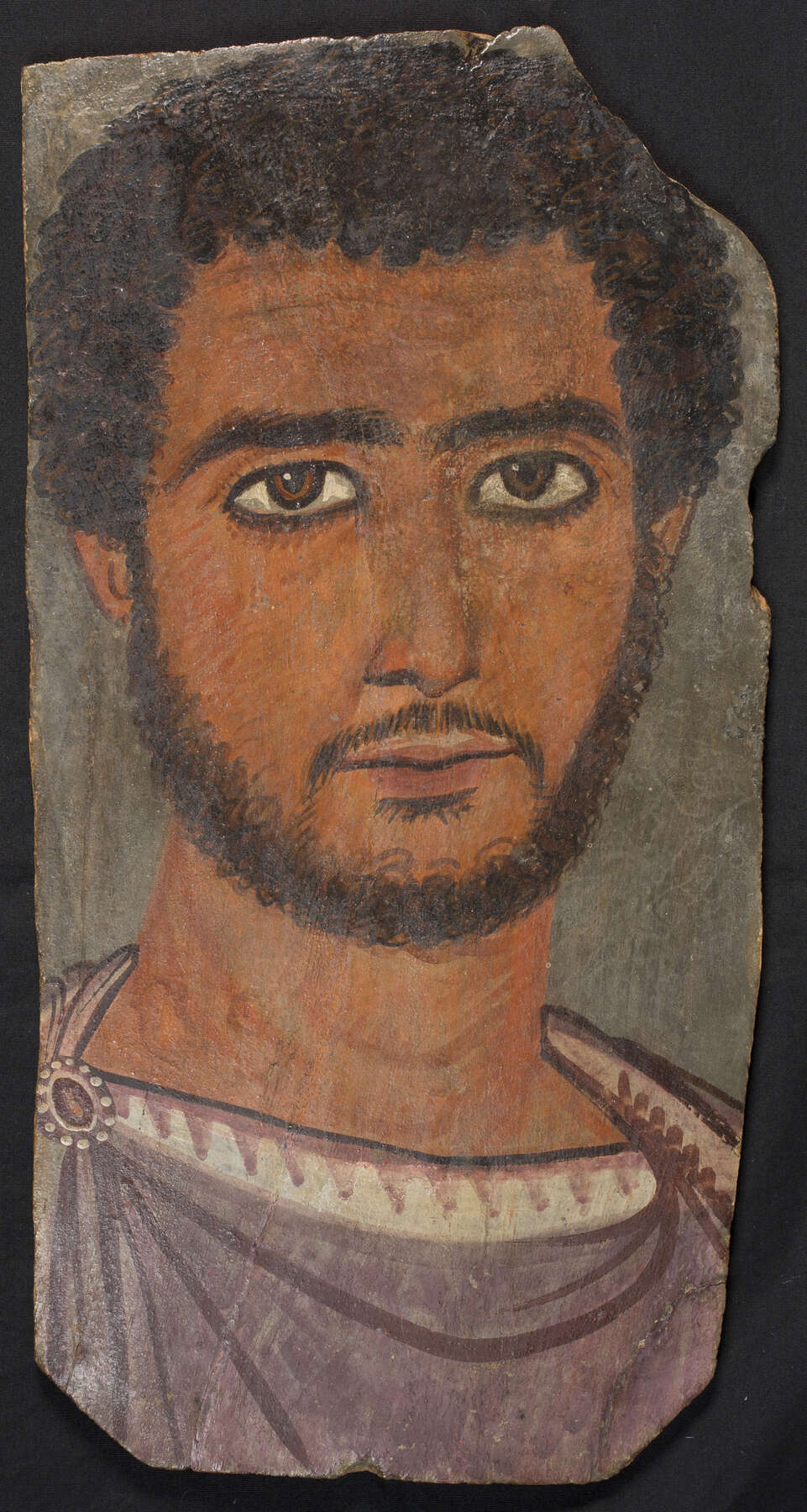

The MFA has twelve Romano-Egyptian mummy portraits in its collection. Funerary Portrait of a Young Man (fig. 8.5) depicts a young man against a dark gray background. He has dark curly hair and a beard as well as large eyes, and he wears a purple tunic; a coating is present on the surface. The portrait was painted in tempera on a wooden panel and based on its painted style is dated to the early third century AD. The work was acquired from an individual in São Paulo, Brazil, in 1959. In late 2016, the MFA briefly had access to a CrimeScope unit. Imaging performed on the portrait clearly revealed similar brushstrokes around the hairline and on the beard when the same 535-nanometer and 555-nanometer narrow bandpass filters were used (fig. 8.6).13 Under magnification, select brushstrokes are slightly visible as hazy areas on the surface; without VIVL imaging via the CrimeScope, these marks could not be identified through visual examination alone. Analysis of the portrait by EEM positively identified madder on the highly concentrated purple of the tunic.14 Likely due to the surface coating, it was not possible to detect madder in any of the areas of the brushstrokes. Figure 8.5

Figure 8.5 Figure 8.6

Figure 8.6

Contextualizing the Brushstrokes

Although the purpose of these enigmatic brushstrokes may never be fully understood, it is clear that ancient artists intentionally employed material in ways more sophisticated than previously known. Underdrawings, although uncommon, made from carbon-based media have been found on other mummy portraits.15 was also used imperceptibly for underdrawings and highlights, and it was added to white pigment to enhance or brighten select details (e.g., eyes and tunics).16 Although the invisible brushstrokes on these three portraits are neither a carbon-based medium nor Egyptian blue, their presence is purposeful. They appear to have been used to create sketchy outlines or underdrawings around the figure on the Penn portrait, to give fleshlike warmth and dimension to the Getty figure’s face, and to add vibrancy, depth, and radiance to the MFA figure’s hair. We hypothesize that the brushstrokes contain madder, an organic material known to fade over time. As such, it is possible that the visual effect of these brushstrokes originally would have been more readily apparent.

The root of the madder plant has been used for textile dyeing and pigment making for millennia, and madder-derived dyes and pigments were available widely in antiquity. As madder is an organic pigment, its appearance and fluorescence are affected by several different factors, ranging from the method of pigment extraction and manufacture to selection. The one material that exhibits a similar fluorescence to madder is safflower; however, it was not commonly used as a colorant on cultural artifacts in the ancient world, and no published occurrences confirming the use of safflower on painted objects from the Romano-Egyptian period exist.17 Unlike many inorganic pigments, madder can be produced to create a range of colors from oranges to reds to purples.18 Madder was a known material in ancient Egypt and frequently incorporated into the palette of funerary mummy portraits, as Newman and Gates discuss in this volume.

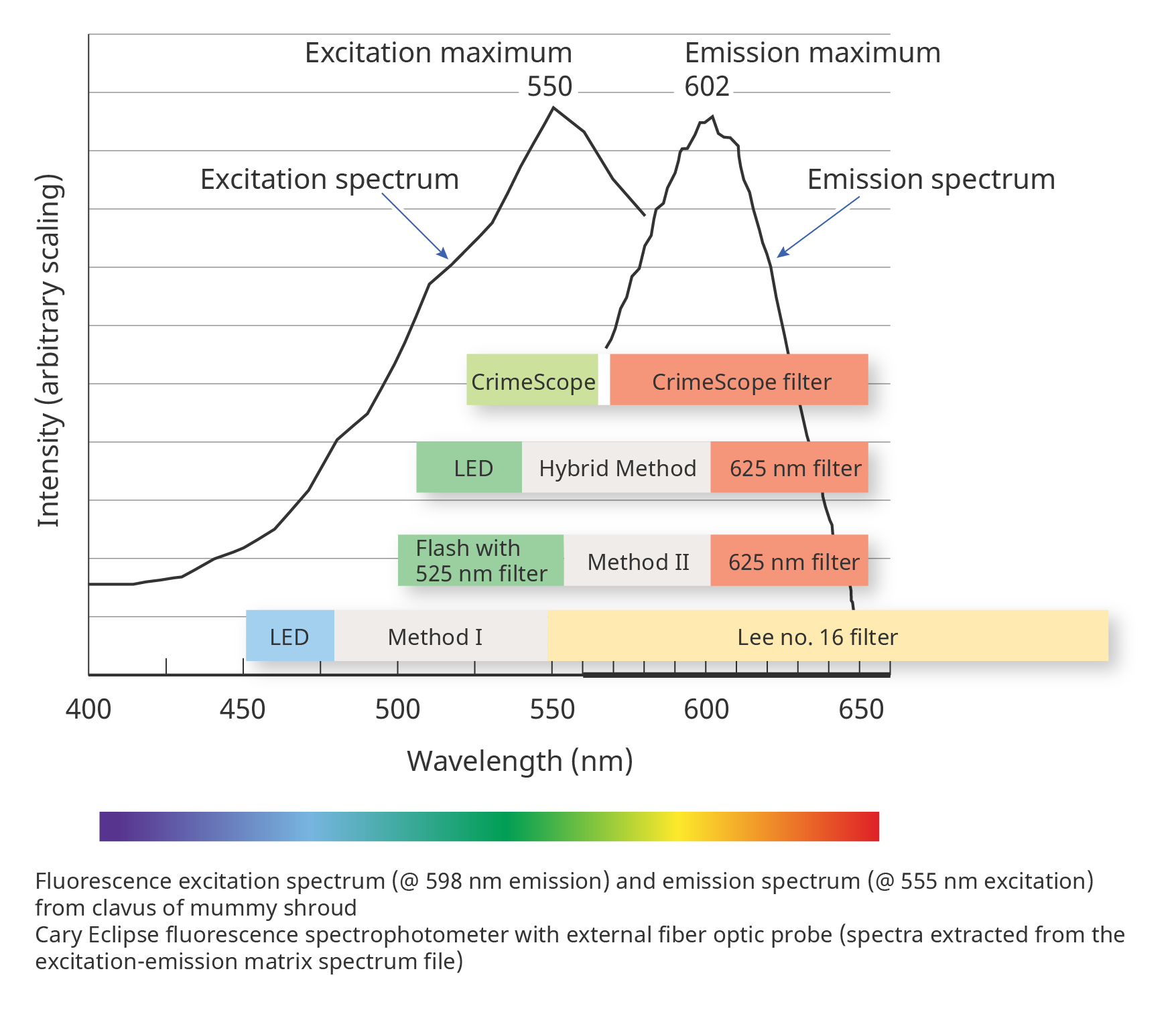

The excitation and emission spectra (fig. 8.7) collected from an MFA mummy shroud depict characteristic examples of madder curves.19 Madder, known to fluoresce strongly when excited and imaged with UV radiation, can often be identified by its characteristic light orange or bright pink fluorescence. Because many materials fluoresce with UV radiation, limiting the radiation to blue or green light closer to madder’s peak excitation wavelength (~550 nm) can reduce the fluorescence noise of other materials and prioritize madder fluorescence. VIVL imaging can achieve this by using narrow bands of visible light to excite the material and a filtered camera system to restrict the range of emission captured.20

Figure 8.7

Figure 8.7Imaging Research Considerations

All three portraits were the subject of extensive analytical research and imaging. The project brought into focus issues of reproducibility and other challenges involved in MSI. The data collected relied on sophisticated techniques executed by experienced users and were discussed with outside experts. Because of the collaborative nature of the project, participants employed precise and internationally recognized terminology. For imaging, the CHARISMA User Manual for Multispectral Imaging21 was adopted. Although some methods of imaging are routinely used and familiar to most conservators, others are not, so all approaches should be clearly documented to assist with their replication and reproducibility.

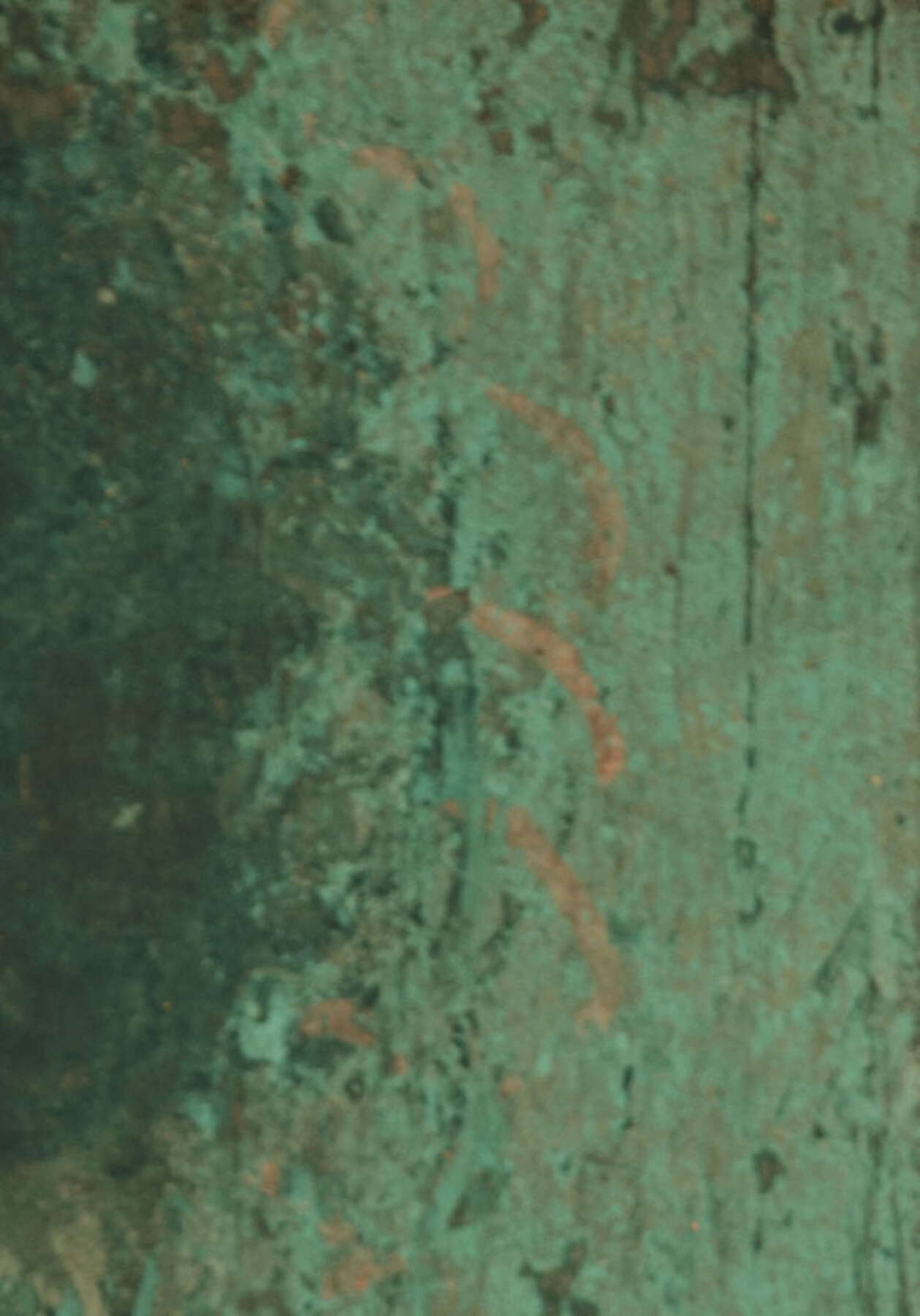

For this paper, some VIVL images were rendered in grayscale (see figs. 8.2, 8.4, and 8.6) to facilitate the visualization of the invisible brushstrokes for publication. One colored VIVL image (fig. 8.8) displays the expected orange fluorescence of madder. Different lighting systems, distance from and intensity of radiation source, filter combinations, and choice of camera can significantly alter VIVL images—consistency even within one institution can be challenging. Carefully reviewing image metadata before directly comparing VIVL images is paramount.22 Figure 8.8

Figure 8.8

VIVL imaging offers exciting possibilities for material characterization as a noninvasive technique utilizing different radiation sources, filter combinations, and digital cameras. More important than suggesting a prescriptive protocol for studying materials with VIVL imaging is to understand the underlying principles. Specific knowledge of spectral curves for radiation sources and filters is crucial. This schematic (see fig. 8.7) indicates the color of visible radiation and filters placed on the camera to illustrate the process. A gap between the excitation radiation source and emission capture window is required to prevent overlap, which can complicate interpretation. Like most analytical techniques, VIVL imaging produces results that should be corroborated with a second imaging or scientific technique.

Although the APPEAR database does not include technical information from all extant mummy portraits, it provides a statistically relevant framework from which to begin evaluating portraits. The discovery of the invisible brushstrokes alone does not challenge the authenticity of the three portraits even if the phenomenon was completely undetected with all other analysis and imaging techniques. More research needs to be conducted with VIVL imaging to contextualize and accurately identify the invisible brushstrokes discussed in this paper and to see if they are present on other portraits. It is important to note that many factors (e.g., coatings, binders) can affect the fluorescence of a material, and one should avoid making definitive statements about objects based solely on material fluorescence.

VIVL Imaging Methods

The goals of this research were to determine the effectiveness and limitations of the CrimeScope and to test comparable, relatively low-cost and user-friendly setups, to enable other institutions to search for similar features on mummy portraits in their own collections. To better understand the appearance of the invisible brushstrokes, different VIVL testing methods were explored. The methods are illustrated here with images of the Penn mummy portrait.23 Additionally, two mock-up boards were created and imaged in order to explore the fluorescence behavior of madder below and through paint layers. The results are discussed in the subsequent sections.

CrimeScope Method

The SPEX CrimeScope is a portable instrument equipped with a high-intensity xenon light that can be tuned to specific narrow bands of light (20–30 nm wide) in the UV and visible ranges (some models have attachments for the near IR). The spectral curves are narrow and steep—ideal for VIVL imaging.24 In addition to the radiation source, the manufacturer provides colored glasses (yellow, orange, red) to facilitate the differentiation of materials.25 Conversations with the manufacturer resulted in identifying comparable camera filters based on the Wratten numbering system. Understanding the spectral curves for both the radiation source (narrow bands at 535 nm and 555 nm) and camera filters (Tiffen 23A filter 50% transmittance ~580 nm) made it possible to target material fluorescence. As a result, the image captured with this setup has a red-orange cast (see fig. 8.8). A regular, nonmodified camera can be used for VIVL imaging; however, to capture a set of MSI images, a modified camera should be used with additional filters so resulting images can be overlaid. Despite the advantages of the CrimeScope, this proprietary instrument has some drawbacks. Given the intensity and the handheld source of the xenon beam, illumination consistency between images can be difficult to achieve. Small discrepancies in the distance between the radiation source and object have a great effect on the strength of the fluorescence emission, and the single strong beam can also flatten images when photographed; however, the most limiting factor of the CrimeScope is the cost, which is generally well beyond the budget of most cultural heritage institutions. That said, the CrimeScope method proved to be the most successful technique to detect the invisible brushstrokes on all three portraits.

Experimental Method I

A recently published article26 presents a new VIVL imaging approach for madder-based pigments using blue LED lights. This method was tested on the Penn and MFA mummy portraits to determine if the invisible brushstrokes could be detected. The excitation source was provided by two American DJ–brand LED lights (dominant wavelength 461 nm). Although the prevailing wavelength is much lower than the peak excitation of madder (~550 nm), the spectrum has a long shoulder. Using camera filter Lee no. 16 (50% transmission at 540 nm) provided a larger acquisition window and gave the images a blue cast with madder fluorescence appearing pink.27 Although the LED lights do not have the same intensity as the CrimeScope, adjustments can be made to the aperture and exposure settings to maximize fluorescence emission capture.

Method I imaging results on the MFA portrait were mixed. Although madder fluorescence was clearly visible on the large, thickly applied blocks of purple paint, such as on the tunic, the painterly invisible brushstrokes were difficult, if not impossible, to detect without prior knowledge of their location. This may be due to the surface coating or to the nature of the brushstrokes themselves. Method I proved much more effective on the uncoated Penn portrait (fig. 8.9). Comparison of imaging results for the CrimeScope method (fig. 8.10) and Method I (fig. 8.11) on the same area of detail of the Penn portrait illustrates that Method I can be used to detect the invisible brushstrokes.

Figure 8.9

Figure 8.9 Figure 8.10

Figure 8.10 Figure 8.11

Figure 8.11Experimental Method II

The Penn-Getty-MFA partnership led to many conversations with conservation scientists and imaging specialists, which led to another VIVL imaging method (unpublished) being explored.28 The excitation source was a Speedlite 580 EX II flash with an XNite 525-nanometer bandpass filter (490–560 nm peak width) attached to the light source.29 An XNite 625-nanometer bandpass filter (590–670 nm peak width) was placed in front of the camera lens. Although both the CrimeScope and Speedlite flash use a xenon bulb, the CrimeScope illumination is continuous and a more powerful light source. Method II lacked sufficient light intensity.

It is unlikely that the invisible brushstrokes would have been detected with Method II alone. The Penn portrait (fig. 8.12) was much easier to image, although the results were dark and the invisible brushstrokes difficult to discern without post-processing enhancement. Potentially, Method II could be improved if a second flash or stronger light source were incorporated. Additional experimentation has yielded mixed but promising results that warrant further investigation (fig. 8.13).30

Figure 8.12

Figure 8.12 Figure 8.13

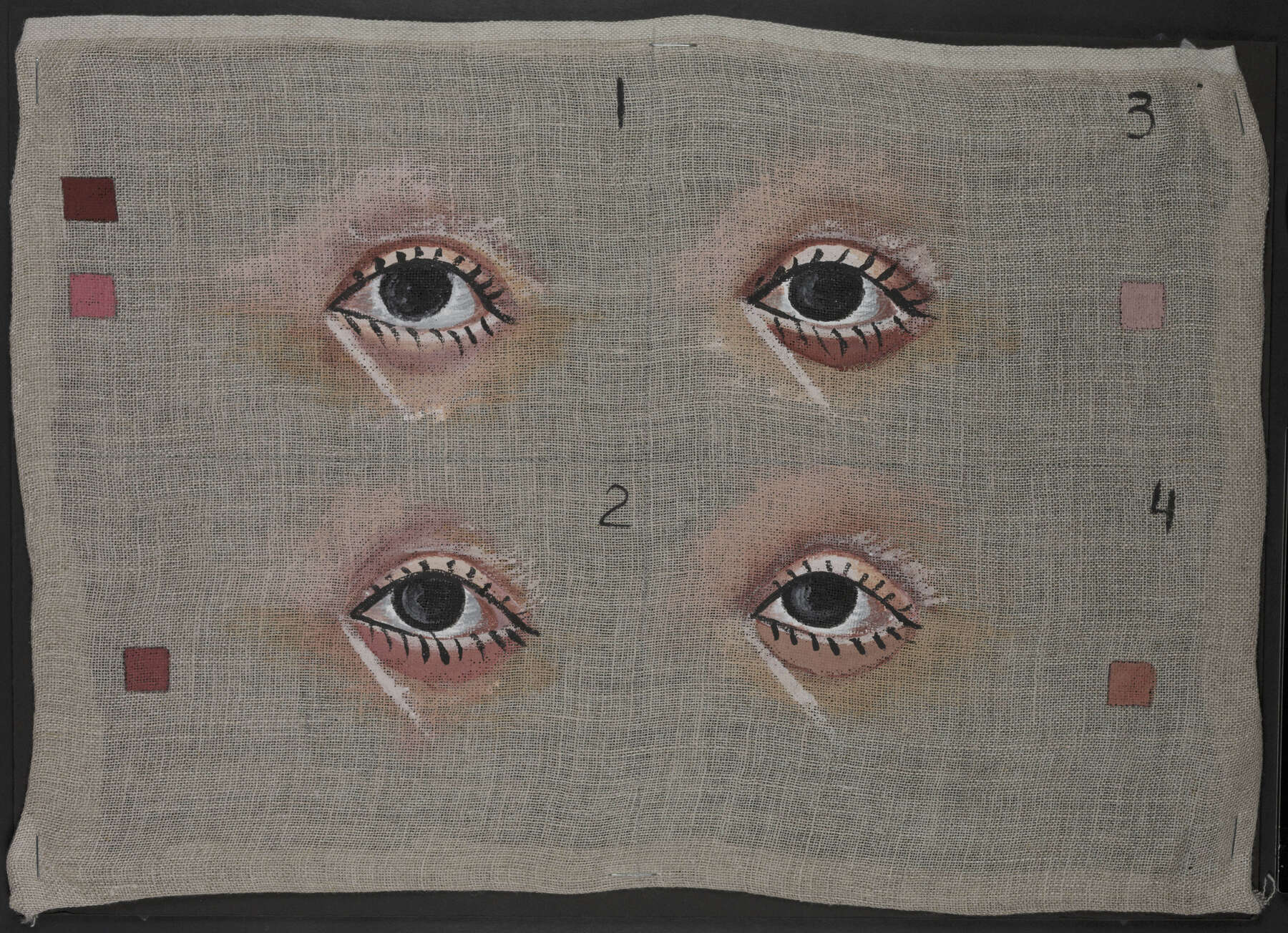

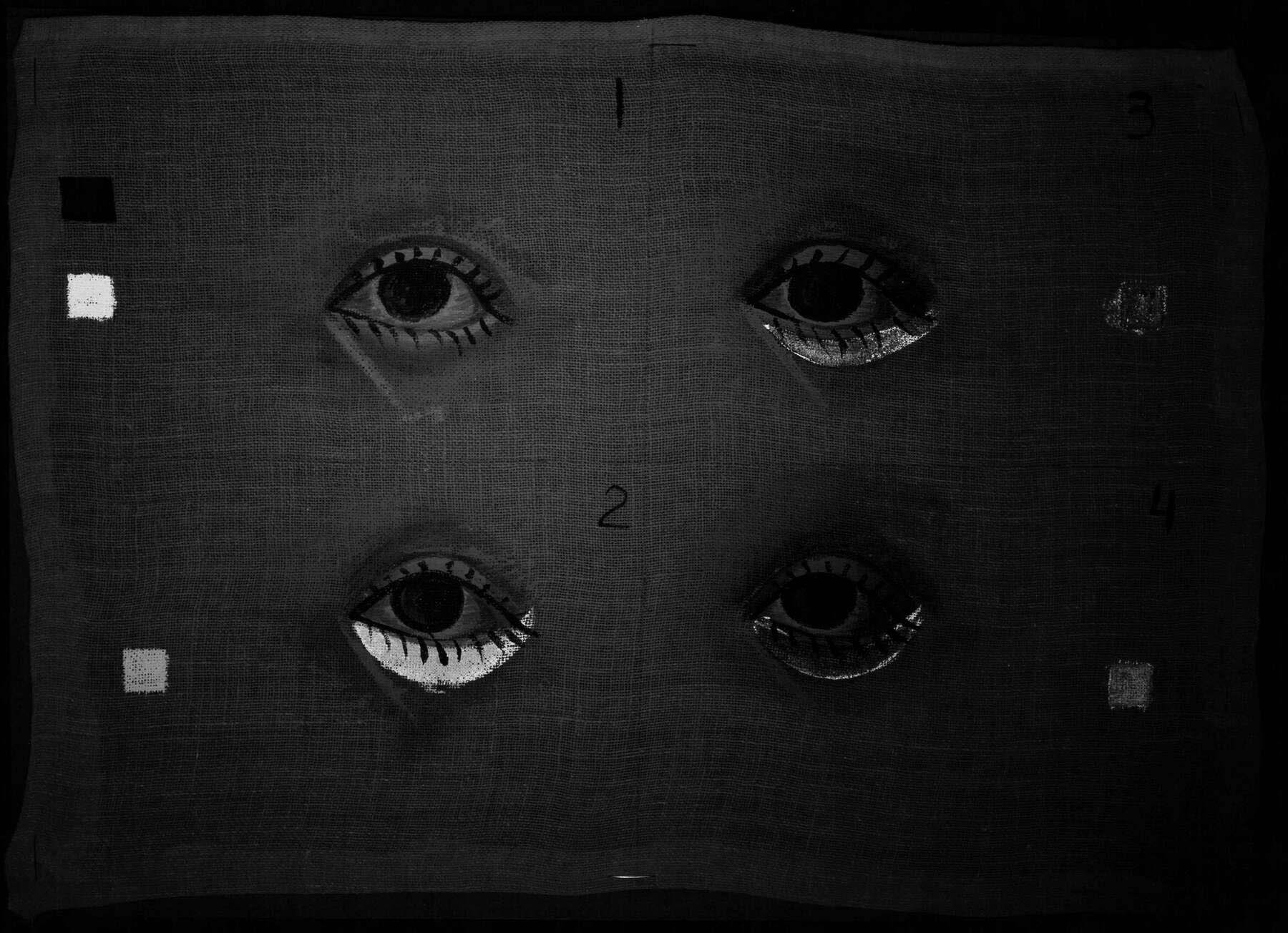

Figure 8.13Mock-Up Boards

To test if madder could fluoresce through layers of , ochres, and lead-based pigments when photographed with different VIVL imaging methods, a mock-up board was created at the MFA. Imaging (UV, VIVL) and analysis (EEM) confirmed that a weak madder fluorescence could be detected when present under layers of umbers and ochres, but lead-based pigments quenched any observed fluorescence. Another mock-up board was made at the Getty to explore the different paint-layer possibilities (fig. 8.14) around the eyes of the Getty portrait. Although visible with the VIVL imaging methods tested, the madder fluorescing through one (#3 on mock-up) and two (#4 on mock-up) layers of hematite is most readily apparent when using the CrimeScope method (fig. 8.15). This trial confirms that the observed fluorescence can penetrate through certain paint layers (e.g., ochres, umbers, hematite) and may suggest a possible paint-layering sequence for the area around the eyes on the Getty portrait. The imaging results of these mock-ups indicate that the CrimeScope, with its powerful light source, is the most effective method of those tested for revealing madder under paint layers.

Figure 8.15

Figure 8.15Conclusions

The Penn-Getty-MFA collaboration enabled the shared discovery of the previously undetected brushstrokes on Romano-Egyptian mummy portraits. Notably, it was possible to detect the brushstrokes only with VIVL imaging; a range of traditional imaging and analytical techniques failed to identify them. VIVL imaging with the CrimeScope produced the best results, due to its continuous xenon-bulb illumination with specific narrow radiation bands. Despite the discussed drawbacks of the forensic instrument, discovery of the brushstrokes would not have been possible without it. Although we had hoped to present Methods I and II as potential, more affordable options for VIVL imaging of the invisible brushstrokes, these alternative VIVL imaging methods produced mixed results; the LEDs and xenon flash did not appear to be strong enough illumination sources to reveal the brushstrokes consistently.

The mock-ups demonstrated that the characteristic fluorescence of madder can be observed even underneath other paint layers if sufficiently excited by an appropriate radiation source. This possibility depends on the thickness of overlying paint and absorbance of the materials in that paint. There must be an adequate amount of both the excitation radiation to an underlying layer containing madder and the emission radiation from the madder for the fluorescence to become apparent to the camera. Other materials in the paint layers (pigments, binders) or coatings present on the surface may affect the ability to observe underlying madder-rich brushstrokes. The condition and materials of the portraits themselves affect the effectiveness of VIVL imaging. Some materials may also fluoresce under the particular excitation wavelengths, and it could conceivably occur (at least in part) in the same region as madder. As such, the invisible brushstrokes described in this paper are not definitively identified as madder (FORS or EEM fluorescence proved inconclusive on the delicate invisible brushstrokes); however, madder was confirmed on other areas of the portraits. It was not possible to sample the invisible brushstrokes in order to confirm the presence of madder at this time.

Given that these invisible brushstrokes were found on three distinct portraits, it is likely that this unexplained fluorescence could be identified on additional examples. Material characterizations and uses may provide evidence for a technique used by specific artists or workshops. We hope that other institutions will be alerted to this unique discovery and incorporate targeted VIVL imaging into their imaging procedures as a means to explore and better understand these arresting and enigmatic portraits.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to a number of individuals for their contributions to this paper, especially Yosi Pozeilov, Richard Newman, Joanne Dyer, Michele Derrick, David Saunders, Pam Hatchfield, Mei-An Tsu, Monica Ganio, Giacomo Chiari, Roxanne Radpour, Christian Fischer, Elmira (Ellie) Adamian, Lydia Vagts, Caitlin Breare, Louise Orsini, Larry Berman, Laure Marest-Caffey, Lynn Grant, Angela Chang, and Walter Hill. The authors would also like to thank the following entities for their support: the APPEAR community; Penn Museum; J. Paul Getty Museum; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; the Conservation Center; Institute of Fine Arts, New York University; and the UCLA/Getty Program in Archaeological and Ethnographic Conservation.

Notes

- While the VIVL imaging technique refers in its name to luminescence, the phenomenon of interest in this paper is fluorescence. ↩

- See ; . ↩

- Published luminescence research on madder roots, aluminum complexes, and madder lakes (solids mainly involving aluminum complexes) shows a range of excitation and emission maxima. Excitation maxima for madder lakes are around 550 nanometers, which corresponds to green light. The intensity of fluorescence will be at its maximum at excitation wavelengths close to the excitation maxima; however, shorter wavelengths also excite the characteristic fluorescence. Narrow bands of other visible wavelengths, shorter than green wavelengths, also can be used to excite madder fluorescence. ↩

- The purple-colored areas (e.g., tunic and clavi) on both the Getty and MFA portraits have a similar fluorescence to that of the invisible brushstrokes when imaged with the CrimeScope. Madder lake was identified in these concentrated purple-colored areas by UV examination and confirmed with nondestructive FORS (Getty) and fluorescence EEM spectroscopy (MFA) analyses; see the APPEAR database. ↩

- Unpublished reports containing these results are in the APPEAR database. ↩

- This archaeological site has several acceptable spellings; this spelling was chosen because it is used in the Penn records. ↩

- APPEAR research at the Penn Museum focused on imaging (radiography, standard MSI, RTI) and the noninvasive analytical technique of pXRF. ↩

- We would like to thank the UCLA/Getty Program in Archaeological and Ethnographic Conservation for the use of their Mini CrimeScope (from Horiba Scientific) in imaging the Getty portraits. ↩

- Carbon-14 date of linen shroud recorded at AD 72–213; see the APPEAR database. ↩

- APPEAR research at the Getty Museum focused on analysis (pXRF, LC/MS, GC/MS, FORS, Raman, , PLM) and imaging (standard MSI, electron emission radiography). ↩

- Pseudopurpurin, a component of madder, was confirmed on the clavi using LC/MS analysis (APPEAR report by R. Newman); this was corroborated by FORS analysis (APPEAR report by C. Fischer). ↩

- Change in institutional affiliation by one of the authors (E. Mayberger) brought the knowledge of this phenomenon directly to the MFA. ↩

- Because of the nature of initial testing with the CrimeScope, many objects were examined in an expedited manner. The pertinent VIVL image captured was unfortunately inadvertently cropped. ↩

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Scientific Research Report 2016-72. ↩

- . ↩

- See , 813. ↩

- Personal communication with Richard Newman, MFA, March 23, 2018; , 279. ↩

- . ↩

- Madder was identified by EEM on a funerary shroud and mask (97.1100) in the MFA’s collection; the pigment was used exclusively to create highlights and volume in areas of the figure’s skin. ↩

- Organic pigments have no significant known fluorescence in the infrared (IR) region; however, it has been published by E. René de la Rie (1982) that a minute tail of the madder fluorescence does extend to the very near IR region. ↩

- . ↩

- Images need to be color balanced, and the incorporation of imaging standards (e.g., AIC PhD Targets, Labsphere Spectralon) is essential. ↩

- The Penn portrait was selected to illustrate the VIVL imaging methods in this paper because the results were the most successful on this uncoated portrait. ↩

- Exact spectra curves for each filter setting were obtained from the manufacturer; however, a nondisclosure agreement was required. ↩

- The filter settings and colored glasses were produced for the forensic field and maximized for common materials of interest. ↩

- . ↩

- If an unmodified camera is used, an additional camera filter limiting the capture region to the visible is needed. ↩

- This method of imaging was developed by Yosi Pozeilov, senior conservation photographer at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. ↩

- To attach the bandpass filter to the flash, matte board and black tape were used to make a temporary mounting system. ↩

- At the MFA, the authors experimented with using American DJ–brand LED lights set on green light (dominant wavelength 526 nm) instead of the blue light used for Method I, and the same XNite 625 nm bandpass filter used for Method II was placed on the camera lens. It was theorized that green light, which is closer to the excitation maxima, would be more effective. The resulting images were not as successful as those obtained from the CrimeScope, but in some areas the brushstrokes were visible. The Penn portrait imaging results with this hybrid method allow the brushstrokes to be readily discernable. ↩