9. Framing the Heron Panel: Iconographic and Technical Comparanda

The four painted of gods in their original frames known from antiquity were all found in the and date to between the first and fourth centuries AD, most likely to the second century.1 A framed panel depicting Sobek and Amun, formerly in Berlin, was destroyed during World War II.2 Only three survive today: one of Sobek and Min in Alexandria,3 one of Heron and a god with a double ax, in Brussels (fig. 9.1),4 and one of Heron alone (fig. 9.2), in Providence, the subject of this paper.

The precise archaeological context of the Providence panel—which was discovered still mounted in its original eight-point frame—is unknown. Likely unearthed in the 1930s, the work was in Maurice Nahman’s collection in Cairo by 1938 and appeared in the sale of Nahman’s collection at the Hôtel Drouot, Paris, in 1953. The Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum in Providence purchased it from Mathias Komor Fine Arts, New York, in 1959.5

Figure 9.1

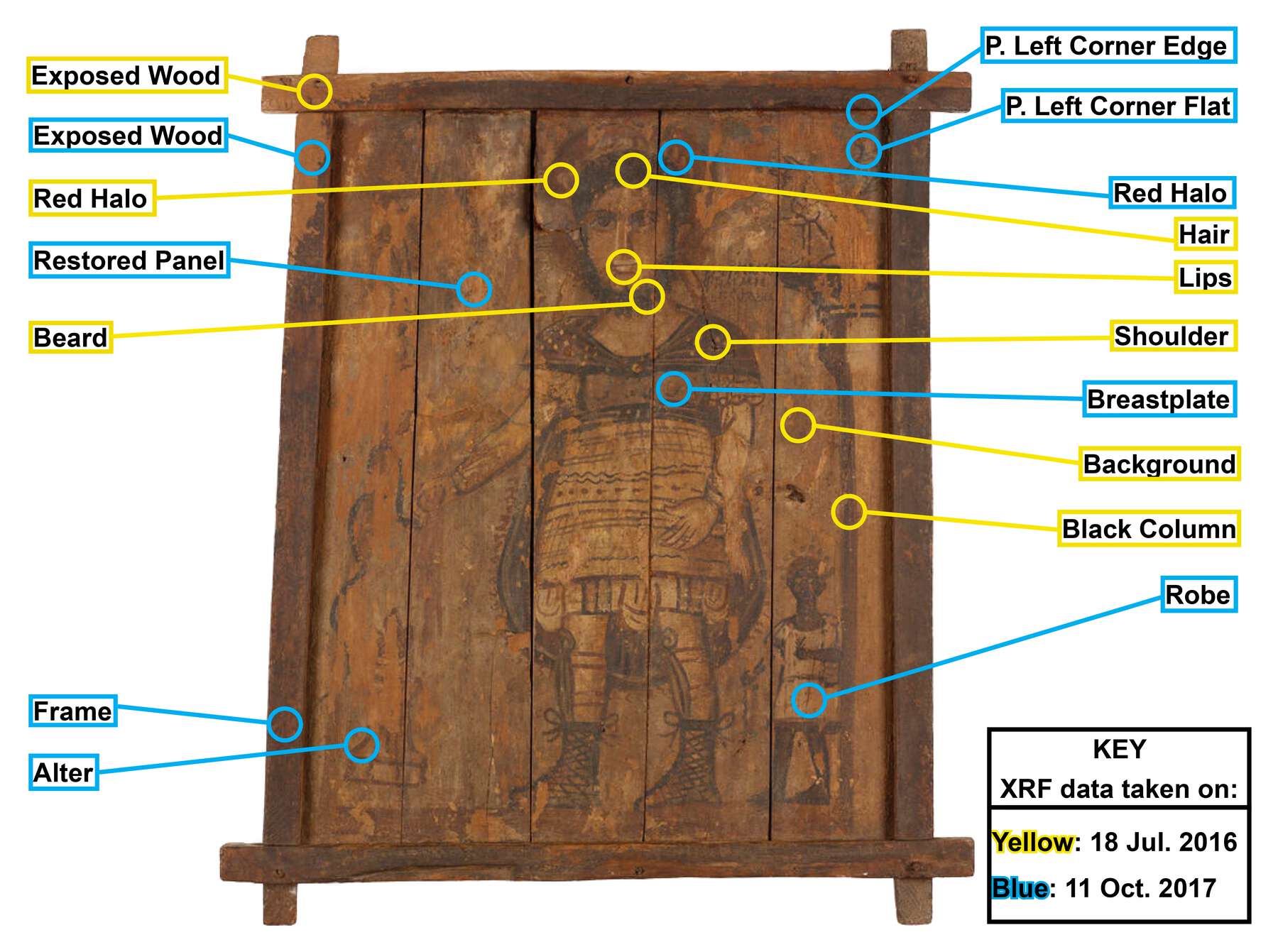

Figure 9.1 Figure 9.2

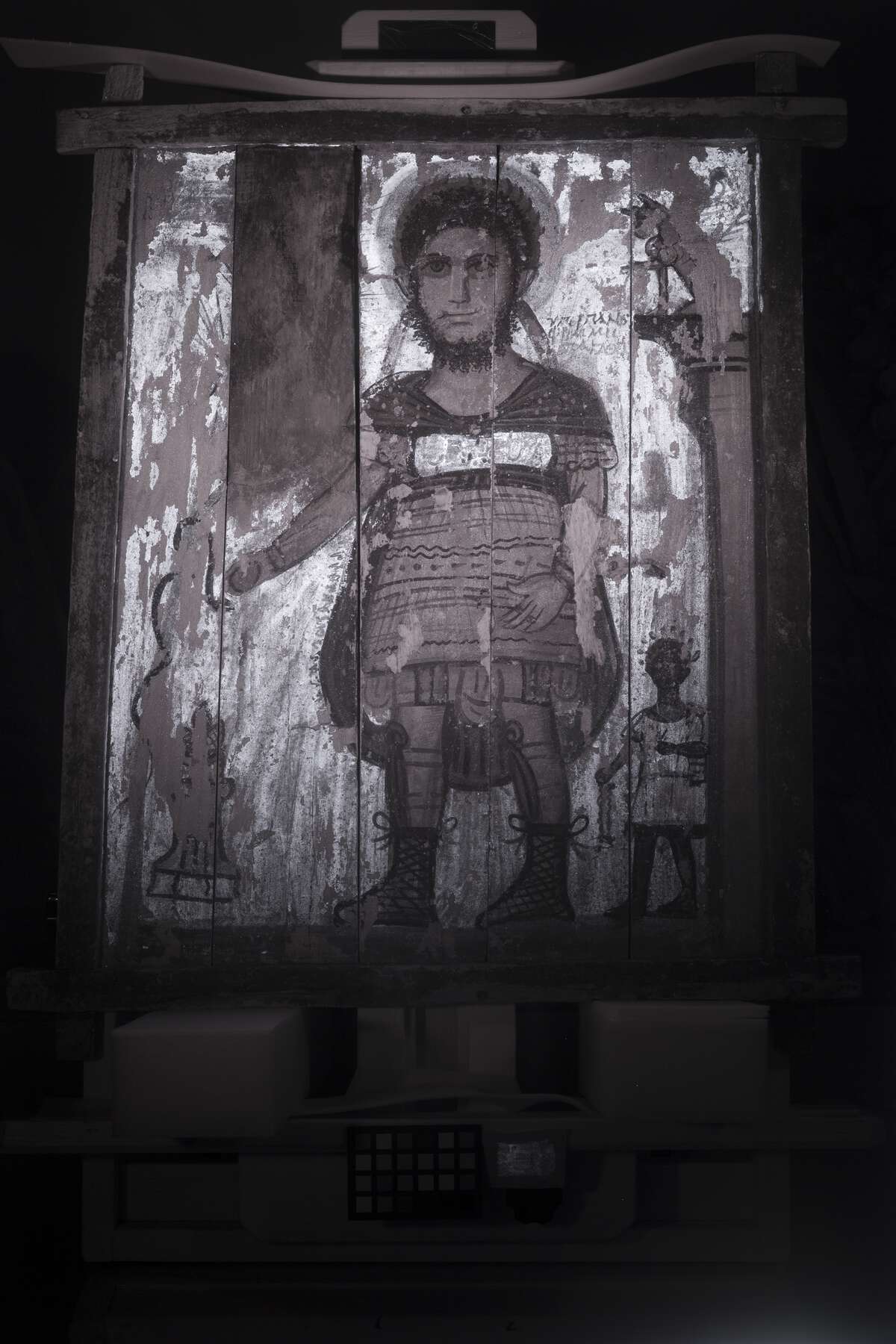

Figure 9.2The RISD panel (see fig. 9.2) depicts the god Heron wearing a cuirass, pteruges, a fringed mantle, greaves, and laced boots. His feet are oriented in the same direction, in the Egyptian convention of depicting standing figures. Bearded and dark haired, his head crowned with a laurel and surrounded by a halo, Heron stares ahead with large eyes. Holding a scroll in his proper left hand, he pours a libation on to the ground from a patera in his right hand, below which is a thymiaterion. Although dressed as a Roman soldier, Heron carries no weapons. To his left a small figure wearing a wreath and a short white offers a rose in his right hand and a bouquet in his left. The griffin of the goddess Nemesis, shown beside her wheel, crowns a column farther to Heron’s left.6 Beside the column is a Greek inscription that translates to “On behalf of Panephremmis, for a favor,” naming the person for whom the painting was offered but not the actual donor.7

Although only a few of these framed panels of gods survive, many more examples must have existed in antiquity.8 The unpainted edges of other painted panels suggest that they were also originally framed. Among them are a panel of Heron in Berlin; one of Heron and a god with a double ax in a private collection in Étampes; one of a goddess, possibly Isis, in Asyut; and one of Harpocrates/Dionysos in Cairo.9 However, not all framed panels portray images of gods, as evidenced by a portrait of a woman found in a grave in , now in the British Museum (fig. 9.3),10 and a portrait of a man in the Getty.11 Figure 9.3

Figure 9.3

In construction, the RISD Heron panel, the largest of the extant framed panels, resembles the panel in Alexandria and the now-lost Berlin panel.12 All three have been constructed of multiple slats of wood held together by an enclosing eight-point frame. The Alexandria panel is composed of three slats of wood, while both the RISD and lost Berlin panels are composed of five slats. It appears that most framed panels were made from multiple slats, though smaller, single-panel examples did exist.13

The figure of Heron has been studied extensively in recent years, especially by the French scholar Vincent Rondot. In his book Derniers visages des dieux d’Égypte and in articles, Rondot reviewed past scholarship on Heron, explored his origins, and gathered and analyzed all known representations of him to date.14 Thomas Mathews explored images of Heron and other Romano-Egyptian panel paintings of gods as precursors to Christian icons in his book The Dawn of Christian Art in Panel Painting and Icons and in previous work.15

Most scholars agree that Heron was not a native Egyptian god, but his origins are still debated. Some believe that he came from Thrace, where he was worshipped by soldiers, and that Thracian settlers brought him to Egypt in the Ptolemaic period.16 Others, like Rondot, believe that Heron originated in the Near East, where he protected travelers along caravan routes.17 Heron gained popularity as a protector god in Egypt during the first centuries AD18 and was featured in wall paintings in various sites in the Fayum. In Karanis he appears dressed as a Roman soldier with a smaller figure by his side,19 while in Magdola, wall paintings depicting Heron adorn a temple dedicated to him.20 His images guard the entrance of the temple of Sobek in Theadelphia: in wall paintings flanking the entrance Heron is depicted both next to a horse and offering incense at an altar in one painting, and on horseback and pouring a libation in the other.21

Although Heron is the sole subject in the RISD panel, save for the much smaller figure beside him, the other painted panels featuring Heron invariably show him standing beside a god wielding a double ax.22 Stylistic details and a similar palette link the RISD Heron to a fragmentary panel in Berlin (no. 15979) that shows Heron with dark curly hair and beard, large eyes, a halo, and a cuirass decorated with a gorgoneion.23 An armed deity, suggested by the upright spear visible next to the tree to Heron’s right, once stood beside Heron in the Berlin work.

A purported shared origin associates the RISD panel with two other Heron panels. The framed panel in Brussels (see fig. 9.1; see note 4), purchased by Franz Cumont in Paris in 1938, came from the same findspot (unfortunately not recorded) as RISD’s panel, according to the seller.24 The Brussels Heron holds both a sword and a spear, in contrast to his unarmed representation in the RISD panel. Next to him is a scowling god, clad in a patterned, belted tunic, checked trousers, and fringed cloak, who raises a double ax in his right hand and grasps a spear in his left. A small figure of a woman wearing a wreath, , and stands to the god’s right. Although this deity’s identity remains elusive, Rondot has proposed that he is Lycurgus.25 Heron and Lycurgus entered the Egyptian pantheon in the Roman period and became a frequently represented pair in the Fayum. In the Brussels panel, both wear haloes and wreaths, with the leaves enlarged and emphasized, perhaps to indicate that in this context they are also associated with the Fayum’s bountiful harvests.26 Although the figures’ proportions are similar in the RISD and Brussels framed panels, the painting styles differ. The figures in both panels are outlined, but the details in the Brussels panel are rendered in a flat, decorative manner within the bold outlines; this style stands in contrast to the attempt at modeling and suggestion of volume evident in the RISD panel.

A fragmentary panel in Étampes has also been linked with the RISD and Brussels panels. Believed to have come from the same site, all three were in Maurice Nahman’s collection before 1938. Both the Étampes and RISD panels appeared in the 1953 Paris auction of Nahman’s collection.27 Depicting the same subject as the Brussels panel, the Étampes panel portrays Heron younger, with a lighter beard. Heron and Lycurgus are rendered in a more painterly style, with shading achieved through delicate hatching rather than blocks of color. Instead of the predominantly warm brown tones of the RISD and Brussels panels, the Étampes image features light purples and pinks as well as browns. Like the RISD panel, it bears an inscription, which translates as “Pathevis, son of Erieus, is the one who [dedicated this work], for a favor.”28 The divergent painting styles employed in these framed panels appear to reflect the variety of styles in contemporary mummy portraits.

The inscription on the RISD and Étampes panels—ep’ agatho, meaning “for a favor”—indicates that these works were votive offerings. Inclusion of the donor’s name in the RISD inscription would not have been necessary if both panels had been offered together; one mention of the donor’s name, Pathevis, would have sufficed.29 In both panels, the inscriptions are placed next to Heron’s left ear so he can hear the donor’s appeals. The size and prominence of his ears are believed to allude to his special powers of hearing, and associate him with Egyptian gods who hear petitions.30 In these paintings, Heron seems to model the proper way to honor him: worshippers should offer libations and incense.

Another ep’ agatho inscription offers a clue to the donor of these paintings. A partially preserved inscription on a fragmentary panel in London likely reads: “[missing name] the dekanos dedicated this painting [for a favor].”31 Although not a high-ranking official, the dekanos belonged to the elite of the Roman administration in Egypt. Thus, the local elite, who were memorialized in mummy portraits, likely also commissioned framed panels of gods.32

Archaeological contexts for certain panel paintings aid in determining their function. The panel of Soknebtunis and Min now in Alexandria (no. 22978) was excavated in the temple of Soknebtunis in Tebtunis, in the second court of the temenos, an area that had become a glass workshop in later Ptolemaic times but maintained some religious function after the temple was abandoned.33 The now-missing framed panel depicting Sobek and Amun (no. 15978)34 and the Berlin fragmentary Heron (no. 15979)35 were found in a house in Tebtunis. When the structure was abandoned in the third century AD, the panels were left on the site, along with the hemp cord and the peg in the wall from which the now-lost panel was hung.36 Framed painted panels in religious and domestic contexts are depicted in many mosaics and wall paintings that have been found outside Egypt.37 A mosaic from a Roman villa in Antioch depicts a man gazing at a framed panel while reclining at home,38 and another from Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli shows a framed panel left in front of a statue of a god in an outdoor shrine.39 The various depictions of framed panels suggest that they were much more common than the handful of surviving examples would indicate.

The evidence provided by these different types of archaeological finds suggests that the framed panel paintings of Heron now in Providence, Brussels, and Étampes were likely installed within a house or a neighborhood chapel.40 These rare surviving religious images from Egypt provide insight into some of the ways that Egyptians conceived of and worshipped their gods in Roman times.

Technical Analysis

Since the time of acquisition in 1959, the RISD Heron panel has undergone three recorded conservation treatments: the first at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1971, a second treatment at RISD in 1999, and a third at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2000.41

The five individual wooden slats that compose the Heron painting were analyzed, as was the attached eight-point frame; all are Ziziphus spina-christi, or sidr wood,42 a hard and durable wood native to Palestine and to north and west Africa. This tree is known to be on the small side, growing only to five meters high. There are many recorded examples of this type of wood being utilized in Egypt; it was used to manufacture both large items, such as boats and coffins, and small objects, such as dowels.43

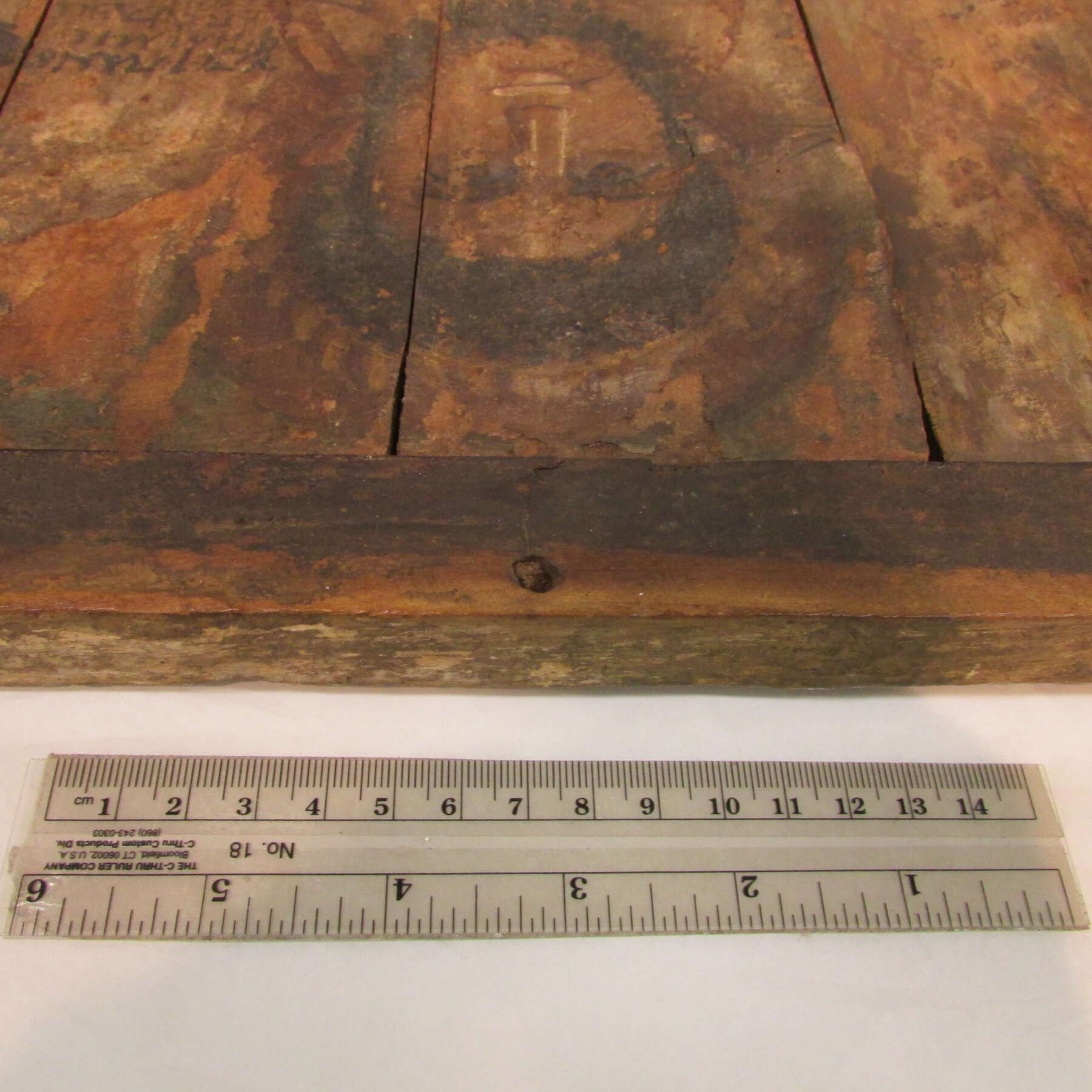

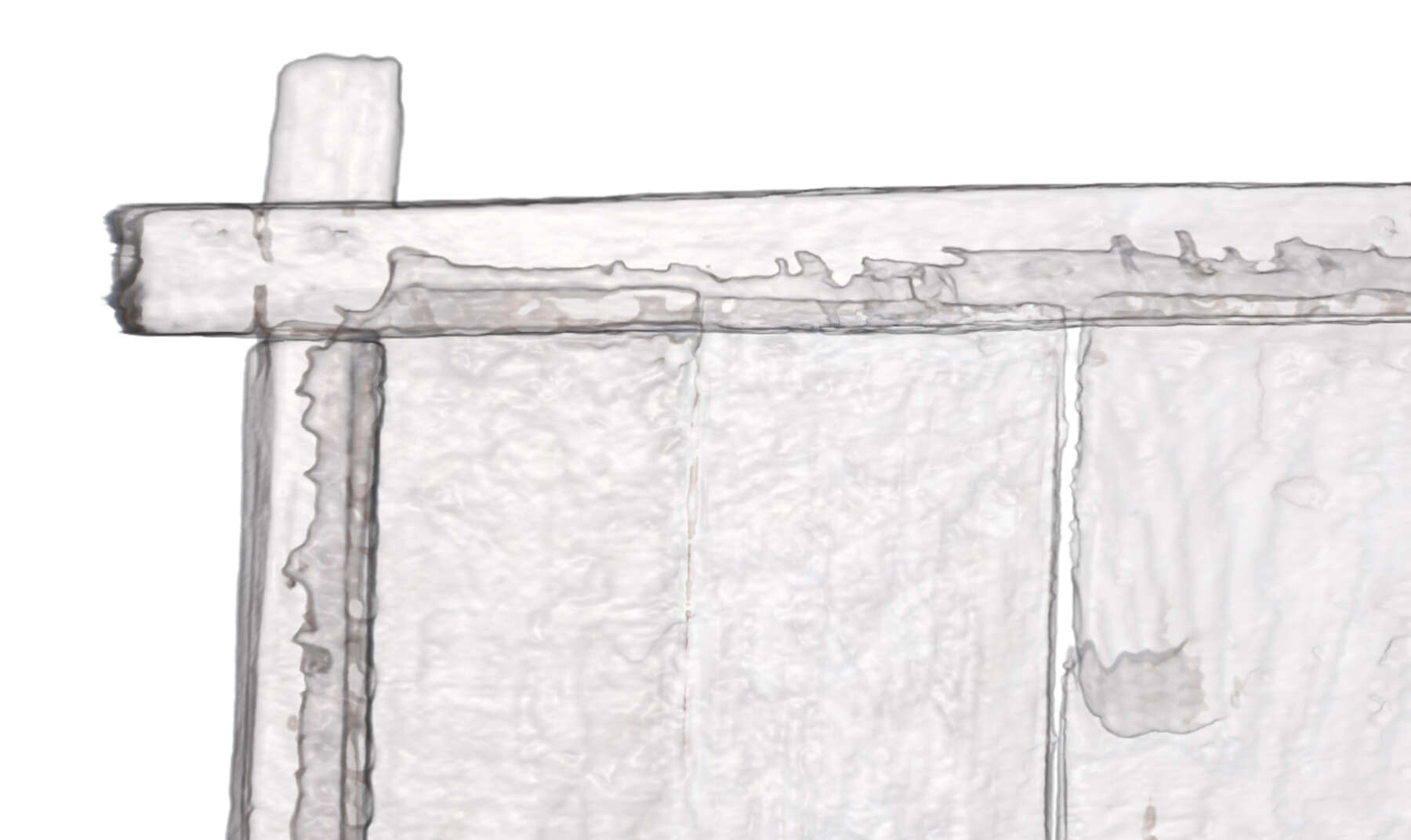

The eight-point frame is constructed of four overlapping individual members that are joined by mortise and tenon with square shoulders, reinforced by wooden pegs that are raised at each corner (see fig. 9.2). Great care was taken in the arrangement of these wooden frame members; the wane edges, meaning those that would have originally possessed protective bark, were placed with the smooth side facing toward the inside of the frame—seen here on the panel reverse. Thus, it would appear that the maker intended to prevent the imperfections in this scarce wooden resource from being visible along the edge of the outer frame (fig. 9.4).44 Figure 9.4

Figure 9.4

Although great attention was paid to hiding imperfections of the frame members, some tool marks, however, were left quite visible—such as the saw marks on the lower tenons and on the reverse of the individual panels. The lack of visible plane marks on the reverse attests to the high skill of the handsaw operator.45

Regarding joinery, the pegs located in the proper left corners of the frame are raised off the surface (fig. 9.5). The raised nature of these pegs suggests that either they may have functioned for display purposes, being used to hang cordage, or they were intended to be accessible and tapped out on occasion, thereby making the frame more easily removable. An alternative theory proposes a deliberate choice by the maker: because these raised pegs would have been an encumbrance or an inherent vulnerability prone to breakage, they might have been an intentional aesthetic choice on the part of the frame maker.46 Figure 9.5

Figure 9.5

Curiously, in the proper upper right corner of the RISD frame, two pegs are side by side; the other corners possess only one. This second peg most likely served as a point of attachment to an auxiliary support (fig. 9.6). Another detail supporting this theory of attachment to an auxiliary support involves the two additional holes, located at the center of both horizontal members, that also possess wooden pegs. These pegs differ from those located at the corners, as they are flush, as opposed to raised. The upper central peg is placed at the midpoint above the middle slat of the painting (fig. 9.7). In contrast, the lower central peg lies along a seam between two of the painted slats. Therefore, the placement of these two central pegs does not appear to be related to stabilizing the painting itself; rather, these central pegs could have been used as a functional mechanism to attach the framed panel to an auxiliary surface.

Figure 9.6

Figure 9.6 Figure 9.7

Figure 9.7The painting was executed once the slats were inserted via tongue and groove into the frame, as dripped from the upper proper left-hand corner onto the inside of the adjacent frame member (see fig. 9.5), which suggests that the frame is original to the painting. This pigment has been analyzed as by and can be seen clearly fluorescing on almost the entire background of this image, except for the portion of the panel that is a modern replacement (fig. 9.8). Paint also extends up the interior surface of the frame members of the Brussels panel, but this does not appear to be the case with the framed portrait panel from the British Museum. Figure 9.8

Figure 9.8

What is particularly interesting about the construction of the RISD panel, as compared with the other two paintings, is that it is composed of five narrow slats of wood. This arrangement of multiple slats differs from the single-panel construction of both the British Museum and the Brussels panels. The presence of a mitered wooden liner also differentiates the British Museum panel painting (see fig. 9.3) from the other two examples.

The five slats on the RISD panel are arranged in an irregular pattern of nonparallel boards with straight edges but not of equal widths; they are not actually rectangular. These irregularly shaped slats reflect the narrow sidr tree boughs, which would have been in limited quantity and therefore a valuable commodity. The alternation of wide- and narrow-ended slats is indeed a sound idea from a woodworking perspective, as the slats are more dimensionally stable in this arrangement. It is clear that all of the edges of the panels have been planed to be straight and that they originally fit tightly with no perceptible gaps. The two slats on the viewer’s right appear to be book-matched, derived from the same tree bough. Based on the wood grain pattern, the center wooden slat might also originate from the same tree bough, albeit from a slightly different location (fig. 9.9).47 These individual slats also contain many knots, one of which appears to be a bark “inclusion,” where bark has grown into a knot and has left a smooth surface when viewed on the reverse.48 Figure 9.9

Figure 9.9

Three-dimensional volume rendering, undertaken at the Rhode Island Hospital, revealed an irregular void along the interior perimeter of the frame (fig. 9.10). Material present in the void may have been an adhesive; however, it is not physically possible at this time to obtain a sample from the interior groove. Figure 9.10

Figure 9.10

In addition to the Egyptian blue pigment, other pigments were identified by means of two rounds of spectroscopy in 2016 and 2017 (fig. 9.11).49 The semiquantitative data are consistent with other analyses that we have completed to date. The presence of calcium and sulfur in all samples is consistent with a binder or, alternatively, could indicate , frequently used as a substrate for . Silicon and aluminum were found in all samples, indicating the presence of a clay. Some interesting findings from the XRF data are the high levels of lead in the lips, indicating , potentially mixed with madder lake. Copper was found in several areas of the painting, including the gray background, the altar, the small figure’s robe, Heron’s breastplate, and even Heron’s red halo. We are confident about identifying the copper as consistent with the presence of Egyptian blue because these areas also fluoresce during VIL analysis.

The characterization of the binding medium by means of infrared microspectroscopy was also conducted.50 The paint sample taken from below the proper right foot produced spectra that indicate that one particle primarily contains gypsum and an oxalate. Another particle primarily contains a stearate compound. An additional organic material, such as an oil, may also be present, but identification by was uncertain. Analysis of a second sample indicates the presence of many inorganic compounds and a water-soluble binder with a reasonable resemblance to plant .

There are notable differences in the wood and the style of frame between the RISD panel (see fig. 9.2) and the small Portrait of a Woman in the British Museum (see fig. 9.3).51 While the RISD panel is composed of five slats of sidr wood, the British Museum panel is much smaller in scale and is composed of a single piece of Ficus sycomorus, sycomore fig wood.52 The fact that the British Museum panel is a single plank speaks to the relatively larger size of sycomore fig wood, whereas the more diminutive scale of the sidr wood corresponds with the narrow slats of the RISD panel. The Brussels painting is also composed of a single panel, but the analysis of its wood has not been undertaken.

Another difference among these three panels is that the British Museum frame exhibits two parallel grooves, whereas the RISD and Brussels frames have only one groove into which their painted panels have been inserted. The British Museum frame appears to have been cut from prefabricated frame stock, as both grooves extend past the mortise and tenon (fig. 9.12). Figure 9.12

Figure 9.12

What would the function have been of the empty uppermost groove, measuring 0.7 centimeters in width, on the British Museum frame? If there were some sort of protective cover, such as a hinged wooden door panel on either side, the existing wooden liner could have served as a spacer to keep the protective doors from abrading the surface of the painting. Interestingly, a wooden hinge does survive from Saqqara in the collection of the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (fig. 9.13).53 Could a similar hinge originally have served this purpose for the British Museum frame? Figure 9.13

Figure 9.13

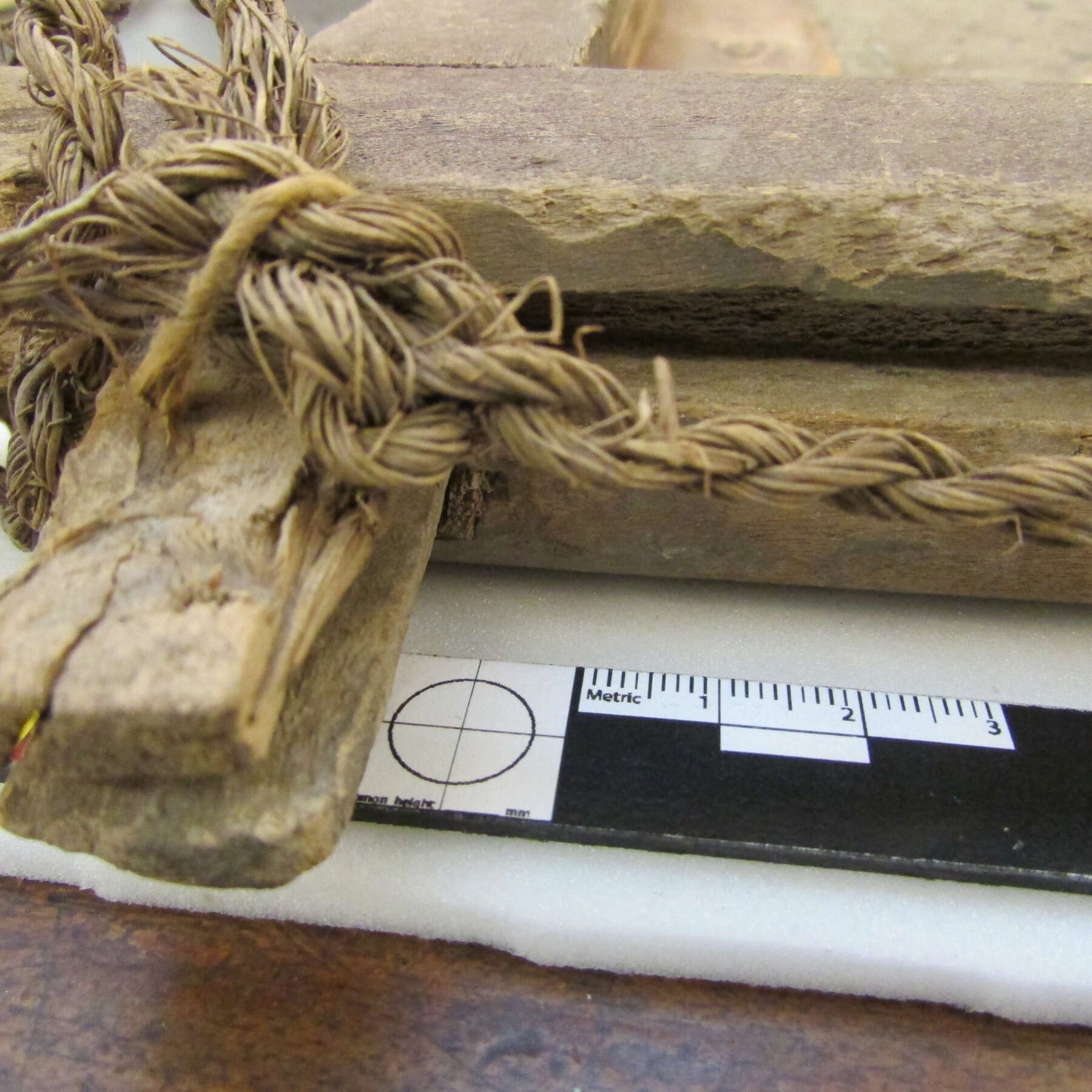

An additional difference among the three panels is that the frames for the smaller, single-plank British Museum and Brussels panels do not possess the wooden pegs that are so prominent in the corners of the RISD frame; however, the British Museum frame is the only example of the three that possesses the braided cordage with which to hang the framed panel. According to the APPEAR website, this cordage has been identified as palm (fig. 9.14).54 Visual inspection reveals that the cordage has been repaired in the modern era with Japanese paper. Figure 9.14

Figure 9.14

Unfortunately, the painted surface of the British Museum panel itself does not survive in good condition. Its surface appears to have a paraffin consolidant, possibly present from the time of excavation.55 In contrast, the painted surface on the Brussels panel is in very good condition. Its surface possesses a matte and lean paint layer similar to that on the RISD panel.

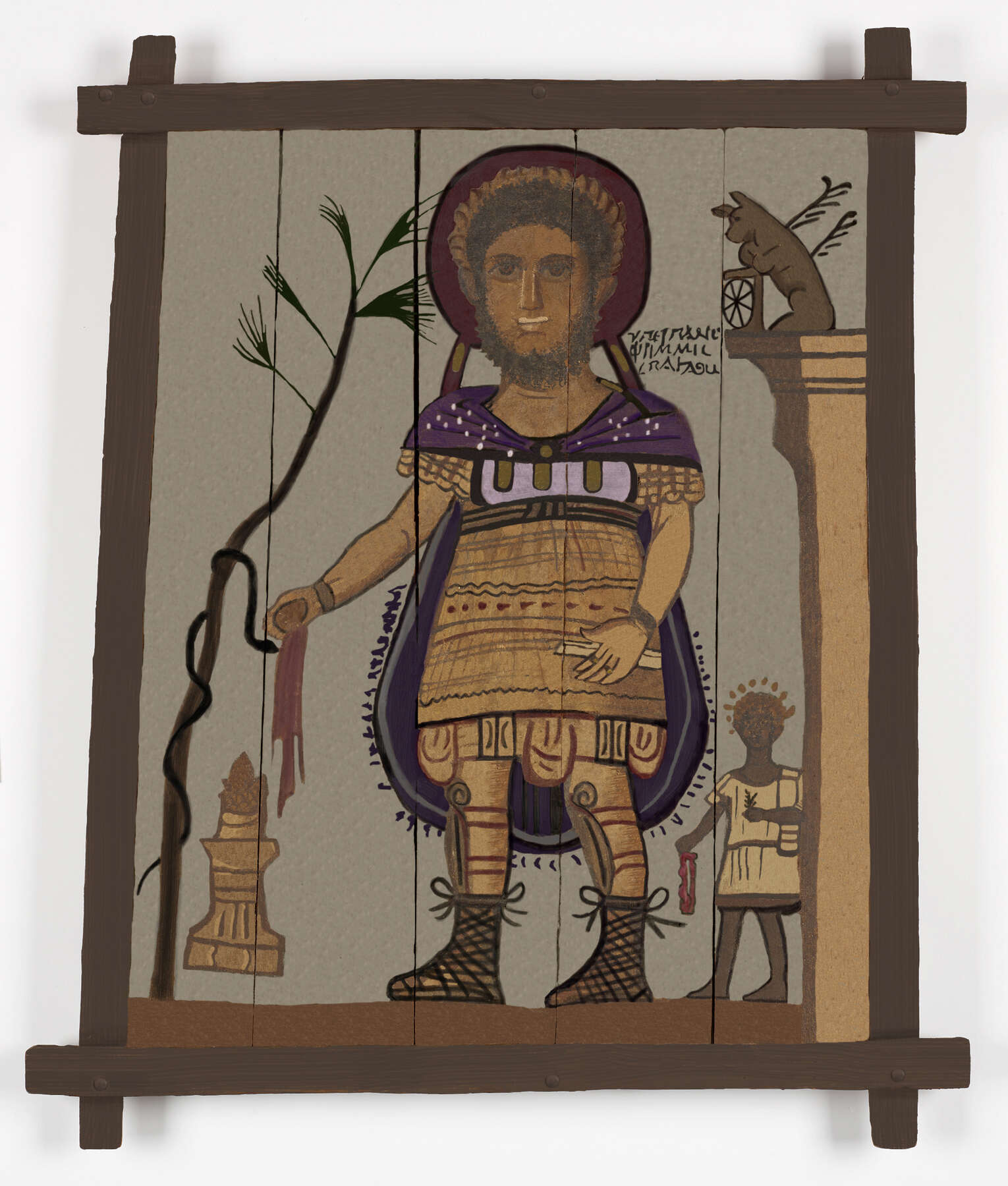

As a midsize institution with a collection of one hundred thousand objects, the RISD Museum was able to contribute to and benefit from this international exploration in a valuable, symbiotic way. The APPEAR project has allowed us to dig deeper within our own collection and explore others located across the globe. Closer to home, it has helped us create new connections and strengthen collaborations with the geologists at Brown University as well as image specialists at Rhode Island Hospital, both of which are only footsteps away from our institution. In summer 2017, an undergraduate conservation intern funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation created a digital reconstruction of the RISD panel as her final project (fig. 9.15). On behalf of the RISD Museum, we are very grateful to the Department of Antiquities at the Getty Villa for the opportunity to participate in this unique and educational project. Figure 9.15

Figure 9.15

Notes

- , 12; . ↩

- Soknebtunis and Amun, Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Ägyptisches Museum 15978; , 122–27. ↩

- Sobek and Min, Alexandria, Greco-Roman Museum 22978; , 75–80. ↩

- Heron and Lycurgus, Brussels, Musées royaux d’art et d’histoire E 7409; , 141–45. ↩

- Heron, Providence, RISD Museum, Museum Works of Art Fund 59.030, accession card and curatorial files; , 5; , no. 286; , 69n66, 243, no. 236; ; , 68–69, cat. no. 37; , 188–89, cat. no. 98; ; ; ; ; , 146–48, no. 34; , 208–12 (with a full bibliography up to 2013 on 208), 283–85; ; , 62–68; , 244. ↩

- According to , 285, this is the only image of Heron with Nemesis, the goddess of divine justice. ↩

- For a discussion of the inscription, see , 138–42. ↩

- A painted sarcophagus from Kerch shows a painted panel on an easel and another hanging on the wall of an artist’s workshop; see St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum P-1899.81; ; ; , 36, fig. 17; , 178–79, fig. 9.2. ↩

1) Heron [with Lycurgus], Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Ägyptisches Museum 15979; , 128–31.

2) Heron and Lycurgus, Étampes, France, private collection; , 152–56.

3) Goddess, Asyut, Egypt, Asyut College Museum 82; , 81–83.

4) Harpokrates/Dionysos, Cairo, Egyptian Museum; , 84–88.

Some of these gods are native to Egypt, some come from the Greco-Roman pantheon, and others, such as Heron, have unclear origins.

↩- Portrait of a Woman, London, British Museum 1889,1018.1; , 121–22, cat. no. 117. ↩

- Portrait of a Bearded Man, Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum 74.AI.20; ; , 146–48, no. 34; , pl. 7. ↩

- See notes 3 and 2, respectively. ↩

- See notes 4 and 10 (portrait), respectively. ↩

- ; ; . ↩

- ; . ↩

- ; , 102. ↩

- , 1–9; , 298–300. ↩

- , 282–300. ↩

- Wall painting of Heron with Lycurgus, from Karanis, exact findspot unknown; , 58–59, fig. 23, note 58. ↩

- , 49–52, figs. 17–18. ↩

- , 52–56, figs. 19–21. ↩

- Heron is often depicted in the company of an armed god in wall paintings; , 52–56, figs. 19–21. ↩

- , 128–31; , 35, 37. ↩

- , 1–2. ↩

- ; , 283–300; , 152–53. ↩

- , 36. ↩

- , 350–52; , 25–26. ↩

- , 138–40; , 208–12; , 60. ↩

- , 140, even believes that both inscriptions were written by the same hand; , 60, 65. ↩

- , 37. ↩

- London, Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College 16312; , 160–61. ↩

- , 65. ↩

- , 48–52. ↩

- See note 2. ↩

- See note 9 (1). ↩

- , 33–37. ↩

- See for a list of wall paintings and mosaics showing framed panels in sacred landscapes. ↩

- Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University Art Museum 1937-264; , 8, fig. 1. ↩

- Vatican Museum, mosaic from Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli; , 89, fig. 2; , fig. 2.10. ↩

- , 5–6, suggests that the panels were installed in Theadelphia, where Heron had a cult presence; , 65. ↩

- Curatorial file, RISD Museum. ↩

- Identification of the wood used for four mummy portraits from the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Caroline R. Cartwright, senior scientist and wood anatomist, Department of Scientific Research, British Museum, November 22, 2016. ↩

- , 347. ↩

- Personal communication, John Dunnigan, professor, Department of Furniture Design, Rhode Island School of Design, February 15, 2018. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- XRF performed by Dr. David Murray, Brown University, using a Delta Professional Olympus Handheld XRF analyzer with an Ag mini X-ray tube excitation source, using two 30-second scans at 40 kV. ↩

- SR Lab project number 2016–243, “IR Microspectroscopy over the Mid-IR Range of 4000–650 Wavenumbers,” Richard Newman and Michele Derrick, Scientific Research Department, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, October 26, 2016. ↩

- See note 10. ↩

- . ↩

- , 18; , 171. ↩

- APPEAR database, https://www.getty.edu/museum/conservation/APPEAR/index.html. ↩

- Personal communication, Lin Rosa Spaabæk, paintings conservator, Copenhagen, September 6, 2017. ↩